Essay Club: Wotan by Carl Jung

"It has always been terrible to fall into the hands of a living god..."

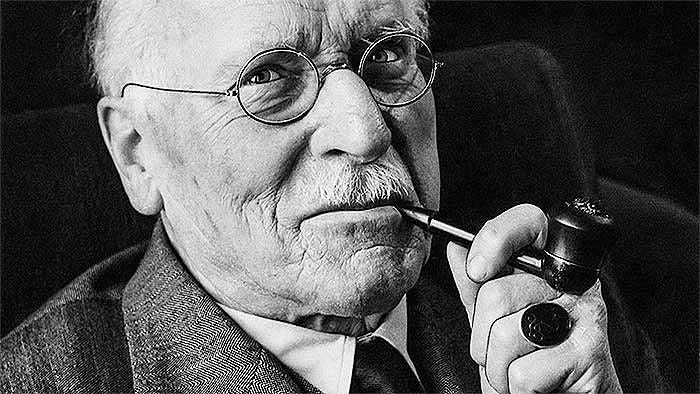

It has been almost two years since I first started Mind & Mythos. In this time I’ve written a lot about psychology, and a little—not enough!—about mythology. It seems strange, then, given my interest in psychology and myths, that I have yet to reference or write anything about Carl Jung. It’s time to rectify this error.

This month’s Essay Club pick is Wotan (1936) by Carl Jung. In this fascinating essay, Jung demonstrates his concept of the archetype by likening the National Socialist movement in Germany to possession by the Germanic god Wotan. The essay takes about 20 minutes to read, and while Jung does assume some prior knowledge of various historical figures and ideas, I think it’s still very accessible without this background knowledge. I highly recommend reading it yourself—but for those who’d prefer a brief summary, I’ve included this interspersed with my own thoughts below.

Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, researcher, and author. He was a prominent psychoanalytic theorist, and his influence continues to be felt in psychology and other more disparate fields today. Like Sigmund Freud, many of the terms and ideas commonly used by contemporary psychologists were first introduced by Jung and his disciples.

Although Jung always thought of himself as a scientist, his methods and ideas have led many to label him, both favourably and pejoratively, as a mystic. He maintained a lifelong interest in religions and myths, and many of his own experiences seemed to straddle the line between spiritual and psychotic. One of Jung’s more controversial ideas—the collective unconscious—is a fine example of this ambiguity. Jung describes the collective unconscious as follows:

“there exists a […] psychic system of a collective, universal, and impersonal nature which is identical in all individuals. This collective unconscious does not develop individually but is inherited. It consists of pre-existent forms, the archetypes, which can only become conscious secondarily and which give definite form to certain psychic contents.” - Carl G. Jung, The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious

To Jung, the collective unconscious is more than just our pre-programmed biological urges or shared cultural memory. There is something spiritual or non-physical about it, and it can only really be understood through the analysis of dreams, symbols, and ancient myths. You can make up your own mind up about that—but for what follows, try to keep an open mind about the nature of this collective unconscious, and consider what Jung really means when he talks about Wotan as a real, agentic force in the world.

Wotan (1936)

It’s 1936: the German people, suffering under the weight of an unpayable war debt, made worse by the financial strain of the Great Depression, have put their hopes in the National Socialist German Worker’s Party—the Nazis—led by Adolf Hitler. Hitler, bolstered by the 1933 Enabling Act, now effectively rules as dictator of Germany. The German war machine is heating up—German troops now occupy the Rhineland, and are deploying to support the Nationalists in Spain—and it’s becoming increasingly clear that another Great War is just over the horizon.

Carl Jung, watching from across Germany’s southern border in Switzerland, was fascinated by these developments. In Wotan, he describes how many others had attempted to explain Hitler’s rise in economic terms, or by reference to mundane psychological or political theories, but that each of these perspectives left something to be desired. Jung offers a different view—as thinkers like Friedrich Nietzsche had already foreseen, the German crisis of the 1930s was a spiritual crisis, one that could best be described as a reawakening of the German soul in the form of the old Germanic god Wotan.

Who is Wotan? In Jung’s words:

“Wotan is a restless wanderer who creates unrest and stirs up strife, now here, now there, and works magic…

He is the god of storm and frenzy, the unleasher of passions and the lust of battle; moreover he is a superlative magician and artist in illusion who is versed in all secrets of an occult nature.”

Throughout the essay Wotan is referred to as a wanderer, a warrior, a berserker, a master of secret knowledge, a magician, and a god of storm and poetry. He is, in short, many things—and to Jung he is inextricably linked to the German folk-soul in both his destructive and creative aspects.

To the modern mind this is difficult to understand. But Jung suggests that if we forego our modern “reasonableness” and make space for metaphysical explanations, we will find that the reawakening of Wotan actually describes the situation very well. Dire economic, political, and psychological circumstances explain some of the events that took place in 1930s Germany, but given that other nations have faced similar challenges without resorting to mass persecution, we have to wonder whether there wasn’t something more going on. Jung proposes that the missing element is Ergriffenheit, emotional seizure or possession. The behaviour of the German people at this time (and indeed, of Hitler himself) looked less like a natural response to economic hardship, and more like a possession—and where there is possession, there must be a possessor.

Is Jung serious? I believe he is. But note this section:

“A mind that is still childish thinks of the gods as metaphysical entities existing in their own right, or else regards them as playful or superstitious inventions… the gods are without doubt personifications of psychic forces…”

To Jung, the gods are at minimum “personifications of psychic forces”. They might also be more than this—knowing Jung, I don’t think ‘childish’ is meant entirely pejoratively—but they are, at the very least, representative of the psychological tendencies (moods, beliefs, motivations, behaviour patterns) of groups of people. The figure of Wotan, then, is what Jung calls an archetype, one that is particular to the German people.

“He is a fundamental attribute of the German psyche, an irrational psychic factor which acts on the high pressure of civilization and blows it away… Wotan is a Germanic datum of first importance, the truest expression and unsurpassed personification of a fundamental quality that is particularly characteristic of the Germans.”

An interesting thing to note here is that Wotan is portrayed as having agency. The Germans did not choose to be possessed by Wotan; rather, he chose them. To put this in terms more agreeable to the modern mind, our unconscious mind is not entirely under our control—thoughts, urges, and feelings will sometimes overwhelm us without any clear trigger, and Jung believes that the same is true of the collective unconscious. Archetypal figures (identifiable clusters of collective thoughts/urges/feelings/behaviours) can emerge or re-emerge from the collective unconscious at any time, seemingly without reason, and possess whole populations.

Where did Wotan come from? Jung tells us:

“For a more exact investigation of his character, however, we must go back to the age of myths, which did not explain everything in terms of man and his limited capacities, but sought the deeper cause in the psyche and its autonomous powers… Man’s earliest intuitions personified these powers as gods, and described them in the myths with great care and circumstantiality according to their various characters. This could be done the more readily on account of the firmly established primordial types or images which are innate in the unconscious of many races and exercise a direct influence upon them. Because the behaviour of a race takes on its specific character from its underlying images, we can speak of an archetype ‘Wotan.’ As an autonomous psychic factor, Wotan produces effects in the collective life of a people and thereby reveals his own nature.”

Let’s break this down. Prehistoric peoples did not think about the world as we do, in a detached, materialist way. Rather, they experienced it first hand—when there was a storm, blizzard, or earthquake, they really felt it; when they felt anger, lust, or joy, they were overcome by it. They had no science or psychological theories to explain all of this, so they relied on stories and intuitions to guide them. In this way their experiences came to be personified as gods, spirits, and demons—and just as each individual is unique in their patterns of thinking, feeling, and acting, so each group has its unique psychological and behaviour tendencies. The tendencies of the Germanic peoples were eventually personified as the god Wotan.

Where does this leave German Christianity? Here Jung is quite clear in his analysis:

“The Mediterranean father-archetype of the just, order-loving, benevolent ruler [the Christian God] had been shattered over the whole of northern Europe, as the present fate of the Christian Churches bears witness. Fascism in Italy and the civil war in Spain show that in the south as well the cataclysm has been far greater than one expected. Even the Catholic Church can no longer afford trials of strength. […]

The ‘German Christians’ are a contradiction in terms and would do better to join Hauer’s ‘German Faith Movement’… There are people in the German Faith Movement who are intelligent enough not only to believe, but to know, that the god of the Germans is Wotan and not the Christian God.”

The German people, in Jung’s view, are not fundamentally a Christian people. Wotan may have been temporarily subdued, but as soon as he saw an opening to return, “the one-eyed old hunter, on the edge of the German forest, laughed and saddled Sleipnir”.

This is where things start to get contentious. One could argue that Jung is saying that Nazism is inherent to the German psyche. This is decidedly not what he's saying—the argument is that the Germans have an innate ferocity and militaristic fervour, and Nazism is an extreme expression of this—but you can see how people might misconstrue this point, and even the softer interpretation is a bit on the nose. I imagine contemporary German Christians weren’t too pleased with his diagnosis.

The other point of contention is Jung's implication that there are inherent differences between racial groups. Now, before World War II, this wasn't a particularly controversial thing to say. ‘Race science’ was obviously the in-thing in Germany at the time, but it was also a fairly well-established area of study across Europe and the USA. After WWII, however, the situation changed. Jung certainly wasn’t a Nazi, but you can see how someone reading this essay after WWII would get that impression. Even more so, perhaps, when we consider Jung’s conclusion:

“We who stand outside judge the Germans far too much, as if they were responsible agents, but perhaps it would be nearer the truth to regard them, also, as victims…

If we apply our admittedly peculiar point of view consistently, we are driven to conclude that Wotan must, in time, reveal not only the restless, violent, stormy side of his character, but, also, his ecstatic and mantic qualities — a very different aspect of his nature.”

To be clear, when Jung suggests that we might view the Germans as victims, he means victims of their own natures—of the wrath of Wotan. I think this is a stretch, but it’s important to remember that this essay was written in 1936, three years before the start of WWII. Nobody could have predicted what happened during the war, nor the outcome, and in a world where the Axis powers won, it’s entirely possible that we might have seen a softer, more Romantic Germany rise from the ashes. Not that this would excuse any of the atrocities committed during the war, but as far as predictions go, Jung’s was as good as anyone else’s.

So what are my thoughts on all of this? I think Jung was an incredibly thoughtful and perceptive thinker. I think some version of his theory about archetypes and the collective unconscious is correct, and I think the more mundane interpretation of archetypes—that they are mythological personifications of a group’s particular cognitive, emotional, behavioural, and motivational tendencies—is a reasonable middle-ground for people who lack a spiritual orientation.

I also think there is some merit to the notion that different groups can have distinct ‘personalities’. Consider how different living in the Arabian desert must be compared to living in the Amazon rainforest; it’s not difficult to imagine how, over generations, this might have an impact on the habits and thought patterns of the people who live there. This is not to say that these habits are hardwired and unchangeable, but I think we can reasonably expect some inter-group differences to emerge out of such different ‘upbringings’. I’m no evolutionary biologist, though—if you have opposing views, please share them in the comments.

Assuming this theory is true, though, it’s conceivable that the Germans might have a Wotan-like character within them. If so, I hope that next time Wotan awakens, he comes in the guise of a poet.

Questions and Housekeeping

That’s it for this month! I hope you enjoyed this one, and I also hope that those of you who are Carl Jung sceptics have found something new to appreciate about his ideas. It’s not for nothing that he remains a towering figure in the history of psychology. Either way, share your thoughts in the comments. Here are a few questions to get things started:

What did you think of this essay, generally?

What do you make of Jung’s concept of archetypes? Are you convinced?

What about the idea of the ‘collective unconscious’?

Is Jung correct that “the god of the Germans is Wotan and not the Christian God”?

If you have any suggestions for future Essay Club essays, please share them in the comments. Otherwise, if you’ve enjoyed this, please take a moment to like, share, and subscribe:

The next Essay Club will be on the 15th of June. I hope you’ll join me to discuss a work by a writer who I feel is one of the more overlooked thinkers of the 20th century—A Defence of Heraldry (1901) by G. K. Chesterton.

Truly fascinating. I did not read the full essay by Jung, but I thoroughly enjoyed your commentary on it. Based on the excerpts and your essay, I think Jung is trying to explain an emergent property of humans. Just as you cannot describe a murmuration with a single bird, you must have a community of humans to see the patterns that emerge---which he frames as "gods" or a collective unconscious. I can see that Jung was an astute observer of human behavior. As a Christian myself, I cannot help but see things through a spiritual lens, and I think the fact that emergent properties of humans exist does not preclude the interaction between the physical plane of reality and the spiritual plane. It seems very likely to me that Jung was conflating psychological principles with the evidence of spiritual action---good or evil.

Thanks, a great summary. Concerning environmental conditioning, I.e., rain forest vs. desert, how do you explain the diff between Eskimo’s and Teutons? They both lived thousands of years in the cold hostile north. And yet their cultures and appearance couldn’t be different.

Also, why is it that of all the vast multitude of human groups only Europeans, and in particular Northern Europeans, have blond and red hair and blue eyes?