Essay Club (Finale): The Cauldron of Reality by Andrew Henry

"We must face the question - did our myths actually happen?"

Welcome to the final instalment of Essay Club! It’s been a fun year-and-a-half, but it’s time to close the curtains on this particular project. To celebrate, I’ve chosen a fascinating essay by another Substack local, Andrew Henry of The Saxon Cross. If you haven’t subscribed to him already, I highly recommend doing so—especially if you yearn for a life more like that of our forbears, one imbued with magic and meaning.

Andrew’s 2024 essay The Cauldron of Reality is one of the most thought-provoking and enjoyable works I’ve read this year. It invites us to reconsider a question that scholars are often quick to dismiss: did our myths actually happen? This is an essay of epic scope, one that both directly references and echoes many of the writers we’ve discussed previously on Essay Club. Like Jung, Lewis, Tolkien, and others, Andrew recognises that myths contain deep wisdom and psychological insights. But he goes a step beyond, speculating that these stories might actually be more historically and metaphysically true than we think. Indeed, our myths might be trying to tell us something important about the future and the very nature of the cosmos.

Is Andrew right? I’d encourage you to read the essay yourself and make up your own mind. For those who are short on time, I’ve provided a brief summary and my own reflections below.

The Cauldron of Reality (2024)

Summary

What do stories like The Odyssey, Parzival, Faust, Star Wars, Harry Potter, and The Gospels all have in common? They are all examples of what Joseph Campbell called the monomyth, the Hero’s Journey, a narrative framework that describes most of humanity’s greatest stories. Narrative tropes like the ‘journey into the underworld’ and the ‘resurrection’, and character archetypes like the orphan-turned-hero and the wise mentor, and are all found in stories from prehistory through to the modern day. Why is this?

Carl Jung theorised that these archetypal patterns emerge out of our collective unconscious, a shared pool of unconscious knowledge encoded into us all by humanity’s earliest experiences. In Jung’s view, these tropes and archetypes resonate with us because they offer psychological insights about important human experiences, such as fear, despair, suffering, overcoming, and transcendence. Andrew sees some value in this theory, but he thinks that Jung doesn’t go far enough:

“The Jungian approach relegates the archetypes to purely mental constructs, which then express themselves in the behavior of human beings. Myth is not ‘real’ in this framework in the sense you’d usually use the word ‘real’. A Jungian thinker like Jordan Peterson might tell you that myths, being archetypal, are ‘realer than real’ or ‘truer than true’, and they are correct, but try to get them to answer whether any of this stuff is literally (as in historically) true and they’ll squirm.

When everything becomes symbolic of the inner quest of the psyche for acceptance, self-actualization, and enlightenment, does it not also become meaningless, because it is no longer tangible?”

In other words, Jung’s interpretation of myth falls short of a more radical view—that our myths are stories about events that actually happened. Andrew speculates:

“Could [the Irish tales of the Tuatha-de-Danann] be an oral history of the Indo-European invasions that displaced the neolithic inhabitants of Ireland? […]

“Could the myths of familial wars in the heavens be a memory of the civil wars of advanced races, perhaps like those from Plato’s Atlantis, races that would have seemed like gods to the simpler hunter-gatherer peoples surrounding them?”

It’s impossible to prove all of this, of course, but there are some undeniable parallels between these stories and what we think of as ‘real’ history. There is also some compelling archeological evidence for the historical existence of many supposedly mythical cities (e.g., Sodom, Gomorrah, Troy, perhaps even Atlantis), which lends further credence to the theory. Given all of this, can we really outright deny the possibility that there might be historical truth hidden in our myths? And if this is the case, is it possible that some of our modern stories hold hidden truths about our history as well?

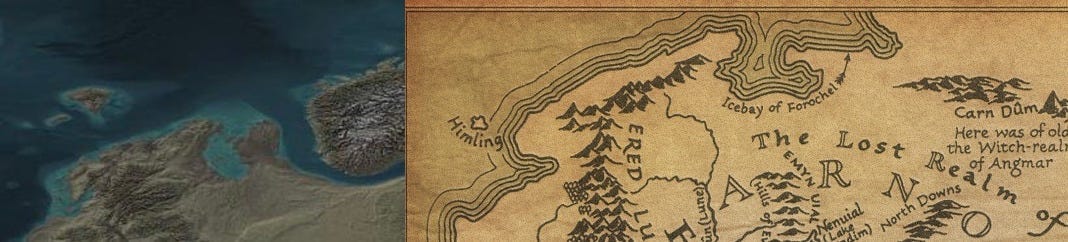

Once again, Andrew offers a compelling argument for this idea. His early work explored the possibility that The Lord of the Rings is exactly what Tolkien always said it was, a true recollection of events from a forgotten, prehistoric age. Andrew points to curious overlaps between the geography of Middle Earth and that of Ice Age Europe as evidence of this theory. For example:

He also notes similarities between our pre-human ancestors (e.g., Denisovans, Neanderthals) and races such as the orcs and dwarves of Tolkien’s stories. His conclusion: “Tolkien wrote tales of an era where men interacted with other kinds of hominids, some friendly, some deadly. An age where heroic men, elves, and dwarves battled ferocious and cannibalistic orcs and goblins.” To be clear, Andrew isn’t saying that The Lord of the Rings is an exact, word-for-word account of historical events. Like the Book of Genesis, the Iliad, and the Enuma Elish, it’s a mythologised account of true history. Abraham, Agamemnon, and Marduk probably all existed in some form, and so did orcs and hobbits.

How could Tolkien have known about all of this? He wasn’t a geographer, and even the most well-read mythologist would be hard-pressed to construct stories and an accurate map of prehistoric Europe from mythological narrative fragments. No, an insight like this requires something more. If we’re looking for an explanation that keeps us within the realm of science, Andrew suggests that the concept of blood memories—in modern parlance, genetic memories—may be the key. We know through research on intergenerational trauma that traumatic events experienced by past generations can have a lasting impact on subsequent generations; one proposed mechanism for this phenomenon is epigenetic inheritance, whereby (as Andrew puts it) “extreme stress can leave a mark on the mind and DNA of an organism, thereby enabling these experiences to be passed down as instincts to its descendants”. Could humans have retained deep-seated emotional memories of prehistoric interactions with ‘orcs’? If so, it’s possible that Tolkien had a unique gift for accessing and interpreting these emotional memories, which allowed him to write myths that seem peculiarly ‘true’.

Is this as far as we can take the interpretation of myth? For the spiritless among us, it may well be. But Andrew, a Christian, is not satisfied with archetypal, historic, or scientific explanations. He goes on:

“If the universe is divinely ordered, if God weaves divine patterns and stories into it, the natural conclusion is that myths are real because they are our way of remembering - and perceiving - the fundamental truths of this cosmic pattern. But in this case we are not only dealing with ‘stories’. A divinely ordered universe following a sacred pattern implies that myths are not only present in the ‘background’ in some sort of symbolic sense (though they are there) but that they must also manifest in our actual, literal, material world. The material world follows the cosmic pattern, just as psychology follows the pattern, and just as our legends and folklore follow the pattern.”

In short: ‘as above, so below’. The fundamental message of The Cauldron of Reality is that “the patterns of reality are fractal”, meaning that everything that ever happens (or has happened, or will happen) is being replicated ad infinitum on the material, emotional, symbolic, psychological, mythological, and spiritual planes. Reality is not arbitrary; it can be likened to a great story with many recurring events and characters, some major and many more minor. There are stories within stories within stories, some mythical and many mundane, and all are variations on the one Divine Story.

“Just as our past was molded by the mythic patterns, so must be our present and our future. The myths are ongoing, as the “pattern” will continue to manifest itself as long as the cosmos exists. Myths are happening among us, our current events are just as mythic as the past.”

The story goes on! Our myths were never intended to just be read and discussed in obscure academic journals. They are iterations on the Divine Story, and the Author of this story has invited us to participate in it. Our myths are meant to inspire us to be heroes in our own lives, to add new chapters to this great book.

The essay ends on a hopeful note:

This should be a comforting thought: that no matter how bleak things may become, and no matter how far Man may fall into darkness and despair (and fall we will), the divine pattern goes on, and the myths will not die. No tyrant, no new world order, no governing body can do anything to change this. The flame may flicker, but it will not die. There will always be a seed ready to take root, even amidst the darkest of times.

And some little boy somewhere, unprompted, will take up a stick from the street, and something inside of him will know that it is a sword fit for slaying dragons. And years later, when that little boy is grown, he may find his true sword, and look the dragon of his day dead in the eye. And so long as he does, the great tales will never end.”

Commentary

This essay is a masterwork of research and imagination. It’s incredibly ambitious—to tie together so many different thought-strands from mythology, philosophy, theology, psychology, and science is no easy task—but the end product is an essay that is both inspiring and intellectually stimulating. I’ve read it several times over, and it never fails to fill me with a sense of wonder and heroic inspiration.

The Cauldron of Reality can be read as a natural progression of the ideas explored by Tolkien in his essay On Fairy-Stories (discussed in my previous Essay Club). Consider Tolkien’s conclusion:

“The Gospels contain a fairy-story, or a story of a larger kind which embraces all the essence of fairy-stories. They contain many marvels—peculiarly artistic, beautiful, and moving: “mythical” in their perfect, self-contained significance; and among the marvels is the greatest and most complete conceivable Eucatastrophe. But this story has entered History and the primary world; the desire and aspiration of sub-creation has been raised to the fulfillment of Creation.”

What Andrew offers is a stronger version of this idea. Stories like Parzival and The Odyssey are not the story, but merely a snapshot of something greater. We will never fully comprehend this bigger story, but by focusing on particular characters, particular events, and particular themes in its sub-stories (our myths and legends), we can meditate on a few key ideas and incorporate them into our own lives. In this way, we can align our own stories with the Divine Pattern without being overwhelmed by it.

Andrew also offers an explanation for something that Tolkien struggled to prove: that memories of our ancestral past can reassert themselves through our stories. We might quibble over certain scientific details—the idea that trauma can be passed on via epigenetic inheritance, for example, remains controversial in some circles—but I think this is a minor point of disagreement, one that will eventually resolve itself as science progresses. The larger point about the rediscovery of our past through stories seems intuitively right to me, and Andrew has provided a plausible, testable theory to explain this phenomenon in scientific terms.

Andrew’s conclusion speaks to one of the great tragedies of our age. We all know that men are in a bad way right now, facing declining grades in schools, higher dropout rates from universities, increasing rates of unemployment, higher rates of death by suicide, and a general sense that there is no longer a place for us in an increasingly feminised world. Many people are wondering why and how this happened. Andrew suggests that men have lost their way because they no longer have heroes to inspire them. The old heroes have been exiled from our curriculum—the Greeks were too sexist, the Romans too imperialistic, the Medievals too Christian, the Moderns too racist—so we are now raised to idolise lesser men, ‘men without chests’ for whom silence is a virtue.

Andrew’s solution: re-enchantment. We need to immerse ourselves once more in the old stories, and teach them to our sons and daughters. Not in the hope of reliving an imagined past, but in order to live new and better stories, stories that are worthy of being written into the Divine Story. I agree wholeheartedly. And whether or not you accept Andrew’s idea of the historicity of myth, or the historicity of Middle Earth, at the very least The Cauldron of Reality works as a powerful new myth through which to re-enchant the world. Any man whose cultural predecessors include Frodo and Aragorn alongside Odysseus, Alexander, Caesar, Charlemagne, King Arthur, and all the other great heroes will be well placed to become a hero in his own right.

For our children’s sake, it’s time to start writing new stories.

Conclusion

That’s all, folks! I hope you enjoyed this final instalment of Essay Club. I won’t be hosting a live discussion this time around, but as always, I welcome you to join the conversation in the comments. No doubt many of you have questions, comments, and critiques to offer. Also, if you enjoyed The Cauldron of Reality, consider a paid subscription to The Saxon Cross. Andrew has written some incredible essays—this was just the tip of the iceberg.

Before I wrap this up, I want to thank those of you who have participated in Essay Club over the past year-and-a-half. Whether you were a regular contributor or a one-time commenter, every one of you has made this worth doing, and I appreciate you all. If you can spare the time, I’d love to hear your thoughts on Essay Club itself. What did you like about it? What did you dislike? What could I have done differently? I’m not planning to redo this any time soon, but you never know who else might be interested in starting a similar project, and they might find your feedback valuable. Maybe you’re interested in starting an essay club yourself—if so, please get in touch. I’d fully support anyone who wanted to keep this going, and would be happy to share what I’ve learned.

As for me… it’s time to get back to what I do best. Au revoir, les amis!

Hm. To be honest, I'm not really impressed by this essay. Maybe it's because I'm in too rational of a frame of mind, but the truly extensive use of the question mark made the whole argument seem rather hand wave-y.

The author has clearly done his research, but the essay itself felt more like a tipsy friend telling you a wild tale than a well argued thesis. I would've liked to see more detail on the research into neanderthals and the other race he conjectured were dwarves, or into the blood memories. Small animal studies showing specific, simple sensory experiences can encoded in short time-frames into genetics just isn't that convincing that by some unfathomably complex mechanism some people are blessed with genetic memory of whole mythologies and stories.

I am quite sympathetic to the argument of the mythology being "more true than reality"/manifestations of divine order. Humans are very, very good at truth-seeking and I think it's intuitive that our most powerful narratives contain deep truths about the universe. Although I'm not Christian, I do have some faith in a sacred order to the universe, although I hold that faith weakly.

Interested why you consider this piece such a masterwork. Some of the speculations were just sorta outlandish and killed credibility for me, such as Star wars being a true or somewhat true divination of the future. Although I guess I am sure the heros journey will repeat many times if we humans spread among the stars (unless we fundamentally change due to ai).

Regardless, loved the essay club as a whole and although I didn't get to all of them I really appreciate what you did by putting these together!!! Sad it's ending but glad you're trying other projects!

Andrew is truly an incredible writer and has often inspired me.