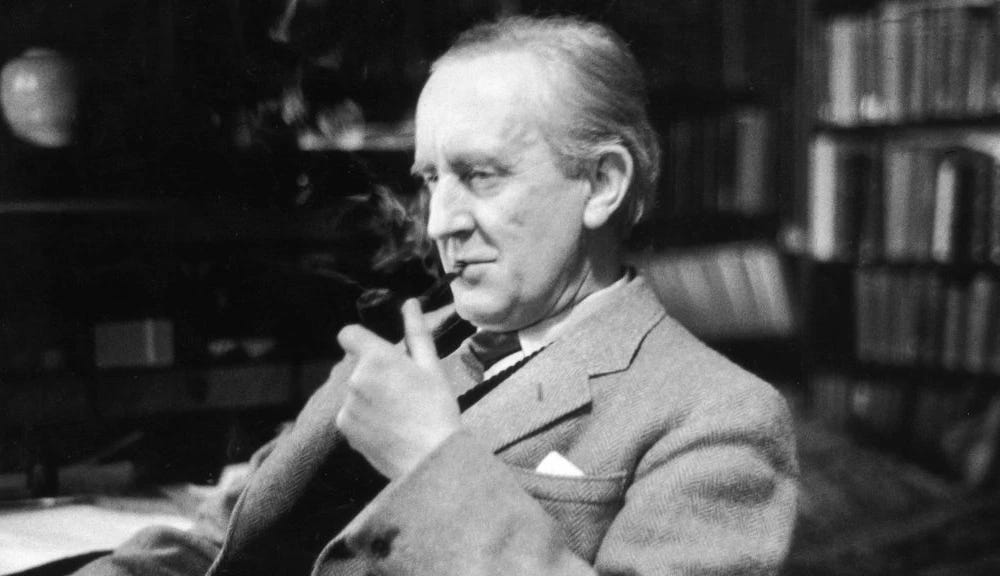

Essay Club: On Fairy-Stories by J. R. R. Tolkien

"The adjective: no spell or incantation in Faerie is more potent."

Speculative fiction (fantasy, science fiction, etc.) is often viewed as less worthy of serious attention than so-called ‘literary’ fiction. Critics will claim that they differ on certain important metrics—quality of writing, artistic experimentation, historical importance, philosophical depth, exploration of the human condition—and in some cases this may be true. But when I compare some of the most popular works from each category, I think speculative fiction holds its own on many of these metrics. Indeed, if I were tasked with writing a list of the best works of 20th century fiction based on these elements, Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings would rank well above (to name just one example) Camus’ The Stranger.

Fairy tales get a worse rap. Stories like Hansel and Gretel and Little Red Riding Hood are generally dismissed as mere children’s stories, valuable only for putting overtired kids to sleep. I strongly disagree. Fortunately, I’m in good company; today’s essay, On Fairy-Stories (1947), written by the great English author and philologist J. R. R. Tolkien, makes a compelling case for viewing fairy tales (or fairy-stories, as Tolkien calls them) as important in their own right. In Tolkien’s view, they are every bit as rich and reflective of our human condition as our greatest novels and philosophical treatises—perhaps even more so.

Is Tolkien right? Let’s find out.

On Fairy-Stories (1947)

Summary

On Fairy-Stories is Tolkien’s attempt to answer three questions. What are fairy-stories? What is their origin? And what is the use of them?

He begins by presenting several prior definitions and ideas about fairy-stories, and ultimately concludes that none of them are satisfactory. The problem is that these ideas don’t get to the heart of what a fairy-story really is: a story “which touches on or uses Faerie, whatever its own main purpose may be: satire, adventure, morality, fantasy.”

What is Faerie, exactly? It’s not an easy concept to pin down. Tolkien defines it as “the realm or state in which fairies have their being”, sometimes called The Perilous Realm. It is both a place and a state of mind; it involves a magic “of a peculiar mood and power”, very different from the popular books-and-wands magic practiced by D&D-style wizards. Its function seems to be to enchant the natural world. Tolkien adds:

“It is at any rate essential to a genuine fairy-story, as distinct from the employment of this form for lesser or debased purposes, that it should be presented as “true.” […]

“Since the fairy-story deals with “marvels,” it cannot tolerate any frame or machinery suggesting that the whole story in which they occur is a figment or illusion.”

A fairy-story, then, is more than just another genre of fiction. It is a portal into the Perilous Realm, a realm in which the natural world is infused with a wondrous kind of magic that we experience as utterly real.

Where do fairy-stories come from? This question has been answered in many ways. Some believe that the various gods and heroes of mythology were originally invented as explanations for natural phenomena (storms, floods, planets, the seasons, etc.), while others say that they began as real historical figures whose stories were mythologised over time. Some thinkers, in an attempt to explain the many cross-cultural similarities between various myths and fairy-stories, argue that these stories spread through diffusion from a single source culture; others argue that these similarities are pure coincidence or, at best, a product of universal human experiences. What all of these theories neglect is the importance of the inventor, or the sub-creator. No matter which theory you believe, in all cases there was an initial moment of sub-creation, the creation of something new from the existing elements of our world. Tolkien gives the analogy of an eternally boiling ‘Cauldron of Story’, into which new settings, ideas, characters, motifs, historical figures and events, and other elements are regularly added by a succession of expert ‘cooks’ (storytellers) to create exciting new ‘soups’ (stories). No cook, no meal.

This brings us to Tolkien’s final question: what are the values and functions of fairy-stories? He has already hinted at some of this, but now he brings it all together. He organises the functions of fairy-stories into four categories: Fantasy, Recovery, Escape, and Consolation.

The first function of fairy-stories is Fantasy. By Fantasy, Tolkien means an act of sub-creation that uses imagined images in a way that ensures the final product maintains an overall sense of internal consistency. Fantasy can be contrasted with other strange phenomena like dreams (imagined images that are internally inconsistent) and other non-fantastical forms of fiction (mundane images that are internally consistent). Fantasy also refers to the unique feeling of strangeness and wonder produced by a fairy-story. This is something that is “best left to words, to true literature”—visual and dramatic arts are unable to create the same effect, because they tend to produce fantastical images that appear too silly or unbelievable. Only imagination, inspired by story and communicated through language, can do Fantasy right. The fairy-story is important because it is the exemplary form of this.

With respect to Recovery, Escape, and Consolation: Earlier in the essay, Tolkien observes that the creation of new ‘soups’ in the Cauldron of Story produces a unique effect: it “open[s] a door on Other Time”, allowing us to “stand outside our own time, outside Time itself”. In other words, reading fairy-stories allows us to experience a transcendent, trans-historical view of capital-T Truth, distinct from the distracting trivialities of ideologies, current events, and strict historical facts. Recovery, Escape, and Consolation are all reactions to this Truth.

Recovery is a “regaining of a clear view”. By this Tolkien means something like “seeing things as we are (or were) meant to see them… as things apart from ourselves.” The strangeness of fairy-stories is important here. It allows us to step outside of the ordinary, and thereby see things that we would otherwise miss under ordinary conditions. Seeing this Truth is the first step toward Recovering it.

Escape is exactly what it sounds like—escapism, the seeking of reprieve from the perils of ordinary life. For Tolkien, this meant escape from the industrialised hellscape of modern England. He notes that critics will often conflate escapism with cowardice, but he’s not swayed by this “tone of scorn or pity”. After all, sometimes escape is necessary:

“Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls?”

Furthermore, Escapism doesn't need to be passive. Recovery and Escape are often the first steps in a more active response to a degraded world:

“Escapism has another and even wickeder face: Reaction.”

This brings us to the last of the four functions, Consolation. Consolation is a feeling produced by fairy-stories in response to our “oldest and deepest desire… the Escape from Death.” Fairy-stories allow us to seek an imaginative reprieve from death through what Tolkien calls the eucatastrophe, the ‘good catastrophe’, a “sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur”. He tells us:

“It is the mark of a good fairy-story, of the higher or more complete kind, that however wild its events, however fantastic or terrible the adventures, it can give to child or man that hears it, when the “turn” comes, a catch of the breath, a beat and lifting of the heart, near to (or indeed accompanied by) tears, as keen as that given by any form of literary art, and having a peculiar quality…

“The eucatastrophic tale is the true form of fairy-tale, and its highest function.”

This is the fairy-story’s greatest achievement: it allows us, just for a moment, to know how it feels to conquer death.

With this idea still fresh in our minds, Tolkien makes one final, surprising leap. In the epilogue to On Fairy-Stories, he notes that “it is difficult to conceive how [a writer can achieve an ‘inner consistency of reality'], if the work does not in some way partake of reality.” The implication is that, if a fairy-story is able to successfully pull of a eucatastrophe (and produce within us the feelings associated with it), it must actually be tapping into something true. The ultimate version of this Truth, in Tolkien's view, is that which is transmitted by the Christian story. This is an important point—Tolkien’s final, most radical point—but one to which I can’t do justice in my own words. So I’ll let the man himself conclude:

“The Gospels contain a fairy-story, or a story of a larger kind which embraces all the essence of fairy-stories. They contain many marvels—peculiarly artistic, beautiful, and moving: “mythical” in their perfect, self-contained significance; and among the marvels is the greatest and most complete conceivable Eucatastrophe. But this story has entered History and the primary world; the desire and aspiration of sub-creation has been raised to the fulfillment of Creation. The Birth of Christ is the Eucatastrophe of Man's history. The Resurrection is the Eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation. […]

There is no tale ever told that men would rather find was true, and none which so many sceptical men have accepted as true on its own merits.”

Commentary

On Fairy-Stories is one of Tolkien’s greatest non-fiction works. It’s by far the longest essay we’ve covered for Essay Club, and Tolkien’s archaic prose style isn’t easy on the modern mind. But it makes an excellent case for what can be achieved through the medium of fantasy, and if we accept his basic position, we must also accept that certain myths, fairy tales, and perhaps even some modern works of fantasy are equal in quality and importance to some of the less fantastical works of the Western literary canon. The Lord of the Rings, at least, is worthy of this honour.

The standout message in Tolkien’s essay is the power of fantasy to take the reader out of ordinary life, to reenchant the world, and thereby grant them a glimpse of a higher Truth. This is something I’ve understood for a long time, and it was gratifying to see it articulated so well by the father of high fantasy himself. By way of comparison, we are also offered an alternative perspective on reality when we read history books—but this perspective stays grounded in material reality, so it misses something important. This ‘something important’ is exactly what fairy tales are about, the world behind the world, a place of spirit and the divine. I was reminded of Simon Sarris’ essay In Praise of the Gods, discussed previously in Essay Club, which celebrates myths, rituals, and traditions as sources of meaning and vitality in an increasingly lifeless world.

I was also reminded of another Essay Club favourite, T. S. Eliot’s Tradition and the Individual Talent. Like Tolkien, Eliot is well-read in his chosen field (poetry), and like Tolkien, he feels that the Tradition of great poetry should be understood as more than merely the sum of its parts. Like great poets, great storytellers in the mythological tradition have what Eliot calls the ‘historical sense’, an innate sense of how their own work relates to the broader Tradition. The best storytellers are able to humble themselves before this Tradition; to extend Tolkien’s metaphor, instead of attempting to make a new soup from unfamiliar ingredients, a wise cook will take inspiration from old soups, borrow certain key ingredients from them, and then ‘make it new’ by adding something novel and important of his own.

On Fairy-Stories is an essay that rewards re-reading. It’s incredibly rich, and it would be impossible for me to comment on everything here. But regardless of whether you agree with this essay or enjoy the works of Tolkien more broadly, you can’t deny that Tolkien was a first-rate thinker, one of the greatest minds of the 20th century. He is, I think, as deserving of a place among the Greats as any other prominent 20th century writer. I place him alongside Eliot, Joyce, Kafka, and the rest.

Housekeeping (and Announcement!)

This was a long one! A big thank you to those who made it to the end. I hope you found Tolkien’s essay as interesting as I did. Your reward: an announcement.

Unfortunately, in June I’ll be bringing Essay Club to an end. It’s been a fun and rewarding year-and-a-half, but it takes a lot of time and work to put these together, and I just can’t commit to writing both my own essays and monthly Essay Club posts anymore. From June onwards I’m going to dedicate myself once again to publishing original essays, ideally at a rate of one per month. Songs of Sarenthé fans might also want to keep their eyes peeled over the coming months—it’s been a long while, but there are still more songs to be sung…

The last Essay Club post will be published on Saturday, June 14th. I want to go out with a bang, so the final essay has been carefully selected for three reasons: (1) it’s written by a Substack native, and I want to celebrate the locals; (2) it touches on several ideas that I personally find very interesting; (3) it references several works and authors that have previously been discussed in Essay Club. Who will it be? Come back in June to find out!

If you enjoyed On Fairy-Stories (or my summary), consider joining my live discussion on the topic. You’re all invited—it will take place one week from now. Details below:

Date/time: Sunday 25th of May, 7:00am Australian Eastern Standard Time [please cross-check this with your own time zone!].

Access link: https://join.freeconferencecall.com/mindandmythos

Simple as—but if you encounter any difficulties with the link, or just want to know more ahead of time, feel free to DM me.

Finally, if you enjoyed reading this post, don’t forget to comment, like, share it around, and subscribe. See you in the comments!

Also been looking into this essay and been analysing. Good essay!