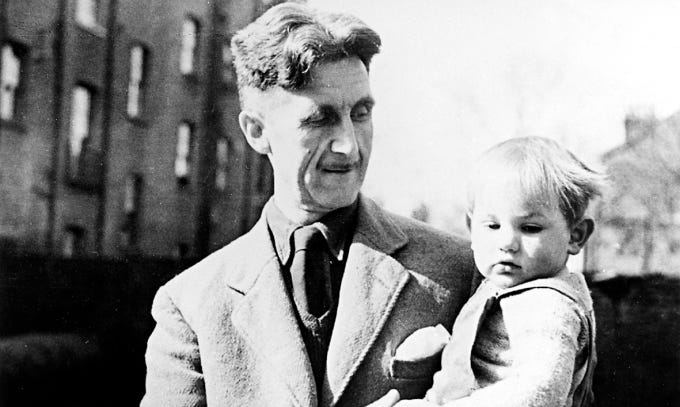

Essay Club: Politics and the English Language by George Orwell

"Political language is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable."

Essay Club kicked off in November of 2023 with George Orwell’s Why I Write. Why I Write is a rather personal essay in which the author lays out the different motivations for writing, admits to his own, and suggests that writing should always have a political purpose (which doesn’t necessarily mean what you think it means). It is one of Orwell’s most beloved essays, so it came as no surprise to me to find, when I looked back at that first Essay Club for inspiration, that it remains one of my most viewed and commented on posts.

In anticipation of the one year anniversary of Essay Club, I thought it might be fun to cover another of Orwell’s essays. This time I’ve chosen Politics and the English Language (1946), a piece that I’m sure many of you have already read. It’s one of the most popular essays of all time—if you haven’t read it yet, now’s your chance. It’ll take you no more than 25 minutes to read, and you’ll come away with a whole new perspective on writing (and maybe politics, too).

Politics and the English Language (1946)

People often say that the English language is getting worse. Some believe this decline is a natural and irreversible consequence of living in a decadent society; as long as society continues to degenerate, they argue, we should expect our language to follow suit. Orwell is more optimistic. While he agrees that our use of the English language has deteriorated, he thinks that language can be shaped, and thus improved. In doing so, we might even reinvigorate our culture. The problem we currently face is that we don’t think clearly:

“A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks. It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language. It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts.”

Orwell believes this decline in our thinking (and by extension, our language) is a consequence of our degraded politics. When certain political topics are broached, “the concrete melts into the abstract and no one seems able to think of turns of speech that are not hackneyed”. In other words, instead of using precise language and making relevant comparisons, we hide sloppy thinking under vague generalisations, and make juvenile attempts to tug at the reader’s heartstrings with overused metaphors. It is ultimately a problem of laziness—a laziness that, over time, turns occasional mistakes into all-pervasive, degenerative habits.

Orwell presents example after example of these bad habits, taken from real contemporary texts. These include outdated metaphors such as ‘toe the line’ and ‘swan song’; the use of ‘verbal false limbs’, short phrases that stand in for simpler words such as ‘militate against’ instead of ‘stop’; pretentious words and phrases meant to give an air of scientific, cultural, or technical elegance, such as ‘constitute’, ‘utilise’, and ‘status quo’; and words that have become entirely meaningless, such as ‘freedom’, ‘democracy’, and ‘fascism’. He is especially critical of the use of Greek- and Latin-derived words in place of their Anglo-Saxon counterparts, as native English words are usually shorter and more direct in their meaning (think aquarium versus fish bowl).

The high point of this section is Orwell’s parody of a verse from Ecclesiastes, using some of the bad habits above:

“I returned and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.1

Here it is in modern English:

Objective consideration of contemporary phenomena compels the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must invariably be taken into account.”

The meaning is the same, but the message is very different. Orwell calls it a parody, but it is not far from the kind of writing that is now commonplace in the American Journal of Psychiatry2.

Orwell warns us to be on guard for this sort of language when reading other peoples’ writing, particularly on the topic of politics. In his words, “political speech and writing are largely the defence of the indefensible”, where passive voice, cloudy language, and euphemisms are often used by politicians and their supporters to justify atrocities. Orwell references “British rule in India, Russian purges and deportations, [and] the dropping of the atom bombs on Japan” to demonstrate this point, and today we see the same rhetorical tricks used in discussions of the Israel-Hamas War and the war in Ukraine.

Orwell says a lot in this essay, and I won’t be able to do justice to it all here, but an important message throughout is that we need to reverse this process. That is, we need to be more intentional with our use of language if we want to improve our thinking and, by extension, our politics. We use vague words and the passive voice when we are not confident in (or want to distance ourselves from) the specifics of what we are discussing. We use foreign, fancy words to seem more intelligent and professional, or to soften the blow when discussing sensitive political topics. Again, this is laziness, and “if one gets rid of these habits one can think more clearly, and to think clearly is a necessary first step toward political regeneration”.

So what can we do specifically? Orwell urges us to write simply and clearly, to pick the right word with the right meaning for the job, and to invent new metaphors that actually make this meaning clearer. True to his word, Orwell is clear and direct in his advice, offering us a numbered list of ‘rules’ to follow:

“i. Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

ii. Never use a long word where a short one will do.

iii. If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

iv. Never use the passive where you can use the active.

v. Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

vi. Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.”

That last rule is worth remembering. To follow Orwell’s advice without exception is to miss the point; the point is to write with purpose, to make deliberate choices that support the message you’re trying to get across. In doing so, we will ensure that we are thinking more clearly about our chosen topic, and communicating this in a way that can be taken in good faith by our interlocutors.

I’ve always enjoyed Orwell’s prose style, so I think the practical advice he gives in this essay is worth following. I intend to re-read it many more times in the future, certainly before publishing any of my own work. I think his broader point is also very interesting, and has some merit. Politics at its core is a high-stakes game of us versus them, and political writing tends to reflect this. When politicians and political theorists write (or speak), they’re not thinking about what’s best for society, but about what society is best for them and theirs, and then saying what needs to be said to achieve their ideal. This is selfish, short-term thinking, and it leads to the kind of sloppy writing and cheap rhetoric that Orwell attacks so strongly in this essay. On the other hand, if we all commit to denouncing sloppy and dishonest writing, we might be able to force lazy writers to think more deliberately about their arguments. This, in turn, could lead to the flowering of a healthier and more considered political atmosphere, which would benefit us all.

Is this really possible? It’s hard to say. But as the 2024 US election date is fast approaching, I encourage you all to consider Orwell’s advice before getting dragged into yet another online political debate. Even if it doesn’t change the behaviour of your opponent, you can work to improve your own writing and thinking, which is worth pursuing for its own sake.

Final Thoughts

What did you think of Politics and the English Language? Did you like it? Hate it? Is there anything important that you think I missed? Share your thoughts in the comments below to get the conversation started!

If you enjoyed this, please give it a like and share it around. Sharing the post is particularly helpful—if more people see it, more people comment, and conversation is the whole point of Essay Club.

Also, you might like to…

November’s Essay Club will be a little bit different. Instead of discussing a single essay, I want to celebrate the first anniversary of Essay Club by revisiting the various themes and ideas we’ve discussed over the course of the year. So I invite you all to meet back here on the 9th of November for a meta-discussion of Essay Club by Dan Ackerfeld. Fun! See you then!

KJV, Ecclesiastes 9:11.

This is not to pick on AJP in particular—all academic journals are like this.