(If you received this via email, please note that this essay may exceed the allowable email length due to the inclusion of images. I recommend reading this one on Substack.)

People used to speak of the three Transcendentals: Truth, Goodness, and Beauty. Most of us still recognise the importance of Truth and Goodness, even if we don't always agree on what's true or good. But somewhere along the way—as even a cursory look at our cities and cultural output will show—we seem to have collectively given up on Beauty as an ideal.

What is Beauty, exactly? I think it’s important to distinguish capital-B Beauty from ‘beauty’ as the word is typically used today. When a man meets an attractive woman, he might describe her as beautiful, meaning pretty or sexy. This is a part of Beauty, to be sure, but it’s not the full picture. Beauty, philosophically speaking, is the often indescribable quality of a thing that makes it emotionally and spiritually pleasurable to perceive. We can point to physical characteristics that contribute to a thing’s Beauty, but there is an experiential element that can never be fully captured. In this essay, I hope to defend Beauty in both its mundane and superlative forms.

I date the death of Beauty to the end of World War II. There were certainly rumblings of an anti-Beauty sentiment prior to this period, with Modern architecture’s asymmetry and rejection of ornamentation, Cubism and other more abstract forms of art, this nonsense, and the move toward more casual fashion trends in the 1920s. For the most part, though, this was limited to a kind of artistic experimentation. It wasn’t until after the war that this dismissal of the aesthetically beautiful became a much fiercer hostility to Beauty as an ideal.

The causes of this hostility were both cultural and material. Post-war Liberal enculturation led to a widespread suspicion of anything that seemed too fascist or traditionalist, including overeager celebration of one’s own national culture and artistic traditions. These traditions were further undermined by the philosophical strains of poststructuralism and postmodernism, which questioned the very foundations of Western values. Without strong values and traditions to fall back on, the emerging Brutalist and International architecture movements were able to dominate in the era of post-war reconstruction. Meanwhile, technological breakthroughs allowed people to explore experimental new artistic and musical forms (some great, many less so). These breakthroughs also led to changes in manufacturing, which allowed for the mass production of ever-more casual clothing styles. These new fashions and artforms, coupled with widespread cultural antipathy to traditional aesthetics and values, birthed counter-culture movements that prized rebellion above all else. Eventually this rebellion took the form of resistance to anything traditional, and anything Beautiful—including ‘traditional beauty standards’.

But didn’t these rebellious teens have a point? Isn’t Beauty in the eye of the beholder? Aren’t traditional European ideals just one conception of Beauty among many? Indeed, perhaps we should feel hostile. These works are, after all, the product of an imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy hell-bent on our oppression. Where’s the Beauty in that?

Beauty Is An Instinct

“The most serious charge against the modern world is its architecture.” - Nicolás Gómez Dávila (Don Colacho)

There are two assumptions that presuppose this perspective on Beauty. The first is that there is no objective standard for Beauty, that what constitutes Beauty is relative to our own preferences and cultural biases. The second assumption is that Beauty is not only relative, but a tool of oppression, in which case we are justified in rejecting Western Beauty norms. We’ll return to the second assumption later; first, let’s challenge the subjectivity argument by exploring Beauty in architecture.

Consider these two buildings:

Northern Ireland’s parliament building is an example of neoclassical architecture. It employs the classical architectural principles of symmetry and proportion, and includes traditional Greco-Roman features such as Ionic columns and a prominent, ornamented pediment. It’s relatively simple with respect to its ornamentation (the neoclassical movement was in part a reaction to the extravagance of the Rococo style), but it’s still beautiful, and in person, an impressive building1.

Scotland’s parliament building is an example of postmodern architecture. It deliberately breaks with tradition—no symmetry, odd shapes and proportions, and built from a variety of artificial materials. It was supposedly designed to “achieve a poetic union between the Scottish landscape, its people, its culture, and the city of Edinburgh”. Naturally, the building is situated in one of the oldest parts of the city, and stands in stark contrast to the traditional architecture of the area. It’s not beautiful; it’s not particularly impressive; one could be forgiven for calling it interesting.

Which building do you prefer? If you're like most people2, you instinctively prefer the classical style. This isn't just a personal or cultural preference. For millennia, artists, philosophers, and scientists have thought deeply about aesthetics, and many have posited an innate human preference for certain shapes and forms. We seem to have a particular preference for forms that imitate nature (a phenomenon known as biophilia), and science suggests that our eyes fixate most on forms with a pleasing degree of ‘organised complexity’. Whatever the explanation, this is all instinctive and pre-rational. If the Stormont building was too wide, if the columns were too bulbous, if the windows were unevenly spaced, it just wouldn’t look right.

Now consider the following works:

These structures, which exemplify the unique aesthetic preferences of three very different cultures, were all built before Europeans had any significant influence over their nations. They display a variety of different shapes and forms, different colour schemes, unique ornamentation, and unique materials taken from their native areas. Nevertheless, many of the same architectural features are present. Close attention has been paid to symmetry, the repetition of motifs and patterns, and the use of distinct geometric shapes; pillars and arches are either included or hinted at, allowing the eye the glide comfortably up the structure; all three structures have somewhat triangular forms, narrowing toward the top; and each structure has multiple ‘levels’ at which we see subtle changes to the base design, which keeps the design fresh and allows for easier horizontal scanning. In short, even where superficial differences exist, beautiful buildings across the globe follow many of the same architectural principles. The fact that these far-flung cultures managed to independently settle on similar forms provides a kind of convergent validity to the idea of universal beauty standards, at least with respect to architecture.

But here's the thing. While all of these buildings have objectively beautiful, aesthetically pleasing features, none of them are truly Beautiful. That indefinable quality is still missing from them. I can only speculate on what this quality is, but my guess is that true Beauty aims at something higher. The glory of God, the deep resonance of myth and music, the grandeur of royalty; we feel an instinctual attraction to these things that cannot simply be explained away. No photograph will ever fully capture this quality, but if you’ve ever visited a place like St. Peter’s Basilica or Neuschwanstein Castle, you’ve no doubt felt it too. It’s sublime.

Beauty is Not About Power

The most dangerous illiteracy is not that of a man who disrespects all books, but that of a man who respects them all.” - Don Colacho

There is an uncomfortable implication in all of this. If a building needs to follow certain rules to be beautiful, then any structure that doesn’t follow those rules must necessarily be less beautiful. It’s here that people start getting defensive. To say that there are things that are more or less beautiful is to make a value judgement, to impose a hierarchy. Many consider this to be cruel and unfair. Wouldn’t it be nicer to simply say that all buildings are Beautiful in their own way?

Clearly, we’re not just talking about buildings anymore. No, what really bothers people is the idea that humans, especially women, might be more or less beautiful. Some have responded to this with outright denial (’all bodies are beautiful’), while others have taken a more critical approach, arguing that:

“modern beauty standards [are] nothing but another projection of patriarchal, heteronormative values, trapping women into an ever-unreachable and suffocating feminine ideal... beauty standards have been and continue to be sold to women as a way of catering to the male gaze, where what is considered to be beauty has been historically shaped by what heterosexual (white) men have desired.” - Are beauty practices liberating or oppressive?

The author (Tammara Lesko), taking the ‘eye of the beholder’ position on Beauty, argues that modern beauty standards have been imposed on women by a culture dominated by straight, white men3. Is this true? Once more, the concept of convergent validity is a useful tool. If a preference for certain physical qualities has been imposed by a dominant culture or group, we should see different preferences in places and time periods where this culture isn’t dominant. On the other hand, if a preference is observed across all (or even most) times and places, we would have to conclude that the preference—and the implied dis-preference—is innate. What does history show?

First, let’s get our baseline. When we look at European history, a particular model of feminine beauty dominates. The 6th century poet Maximianus was the first to describe this ideal at length:

“I shudder[…] at the slender, I shudder[…] at the fat… a cheerful face suffused with pink that blossom[s] with distinctive roses… flowing golden hair… black brows, a confident expression, and black eyes… a bit of pout and sultry scarlet lips…” - The Elegies of Maximianus: Elegy 1

According to Maximianus, the ideal woman is neither too thin, nor too fat. Her eyes are dark, her brows are black; she has long locks of golden hair, rosy-red cheeks, and full red lips that form a cheerful (yet seductive) smile. In short, Maximianus’ ideal woman looks like Marilyn Monroe4.

We find a remarkably similar ideal throughout European history. In ancient Greece, beautiful women had “rounded buttocks, long, wavy hair and a gentle face… large breasts and a pear-shaped body”. Curvy, but not overweight. In the medieval era, we see “golden hair, black eyebrows, white skin, long neck[…], long arms, long thin milk-white fingers, very small waist…”; a thinner ideal, perhaps, but otherwise consistent. In the Victorian era we see a return of the ‘wasp waist’, the classic hourglass figure, with which Marilyn is so strongly associated. There are some superficial differences between cultures (e.g., the Greeks preferred red hair to blonde, the medievals preferred grey eyes to our blue), but all in all, the picture is clear. The beautiful European woman has long, lightly-coloured hair, dark eyebrows, full red lips (with a pleasant smile), white skin with rosy cheeks, and a slim waist with curves.

Does this ideal hold up across cultures? In places where historic beauty ideals are well documented, it certainly seems to. For example, throughout their long history, the Chinese have typically preferred narrow eyes and eyebrows, red lips, fair skin free of blemishes, and a ‘willow waist’ (slim waist)5. This is not a European look, per se, but many of the same traits are celebrated. In ancient Egypt, we see a preference for women who are slender (but not thin), with lighter skin, full red lips, dark almond-shaped eyes, and long dark hair. Unsurprisingly, different ethnic groups tend to prefer their own distinctive traits (e.g., Chinese vs. Egyptian eyes), but otherwise, there is a remarkable degree of cross-cultural agreement on what is considered beautiful. Modern research has also identified several less obvious traits, such as facial symmetry and averageness (“how closely a face resembles the majority of other faces in a population”6), that are universally preferred in both men and women.

The important takeaway here is that none of these preferences were imposed by any single culture or group. There is something about them that we all find inherently beautiful. Researchers argue that we are attracted to them for evolutionary reasons—they are markers of youthfulness, health, or fertility, all of which are important in a partner with whom you hope to procreate—but ultimately, the reason for our attraction is irrelevant. What’s important is that, just like with architecture, we feel in our bones that some traits, and thus some people, are more beautiful than others. It’s not about power—powerful groups may impose their own ideas for short periods of time, but they’ll never fully erase our instincts.

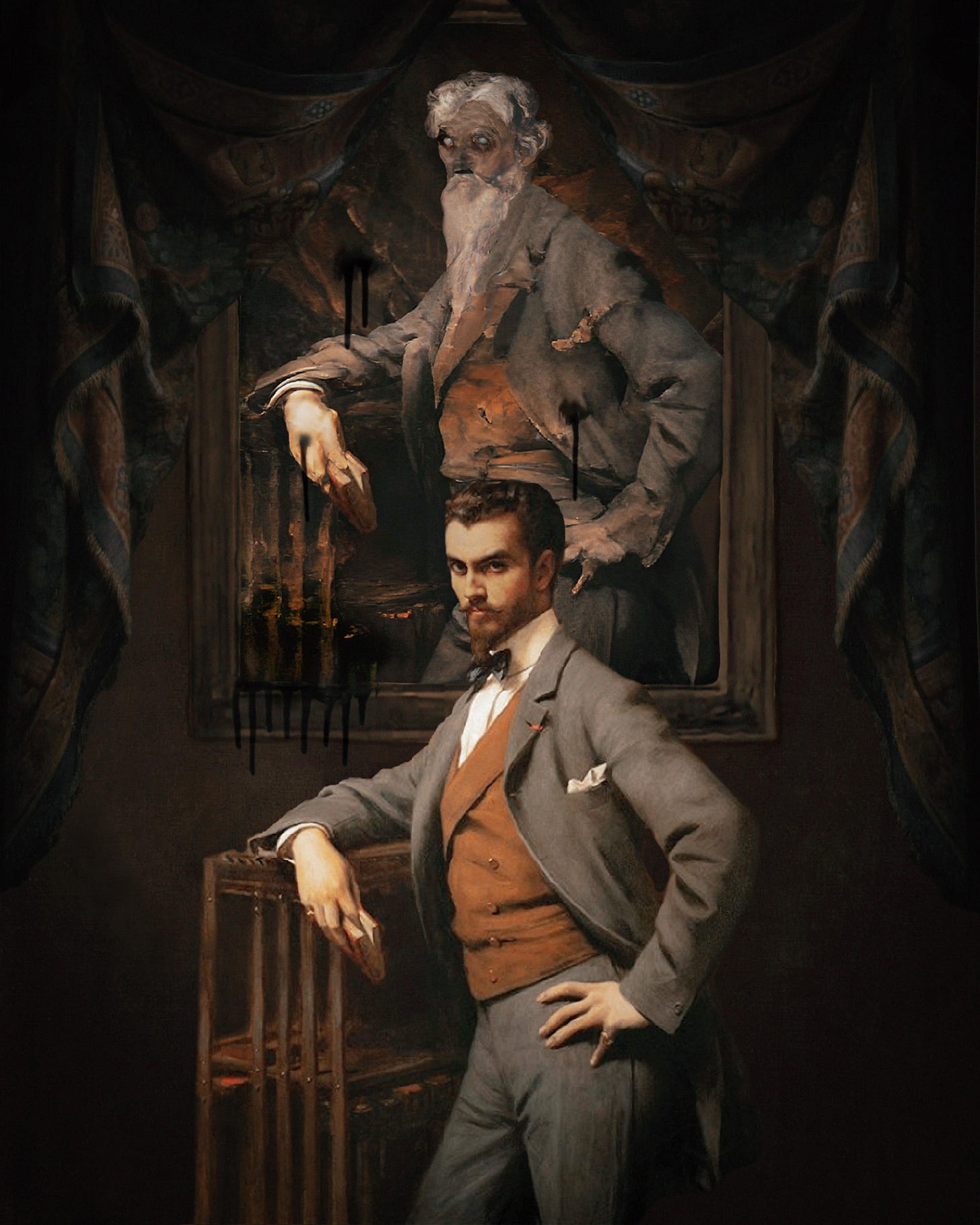

But what of Beauty? Similar to architecture, it seems to be possible for a person to be beautiful without being Beautiful. There are many people who are physically attractive who nevertheless lack a certain quality—an inner Beauty—that only a select few possess, and to which the rest of us cannot help but be attracted. Here again I can only speculate, but I believe this kind of Beauty reflects a person’s genuine pursuit or attainment of a particular virtue, such as kindness, courage, faith, or sincerity. When we see it, we often call it charm or charisma; whatever it is, it’s a reflection of a person’s aspiration, conscious or otherwise, toward something higher.

Final Thoughts

“Beauty is vanishing from our world because we live as though it does not matter." - Roger Scruton

Is beauty in the eye of the beholder? Clearly, the answer is no. Beauty has ‘rules’, and there are things that simply are and are not beautiful. There’s still room for personal preference, of course, but the fundamentals must remain largely the same. No amount of oppression or enculturation can change this instinct.

It’s the same for Beauty. There are certain virtues and moral qualities that, when aspired to, can elevate something mundanely beautiful to a position of transcendent Beauty. But not all values are equal. If we believe things that are morally wrong, attempting to make art from them can only produce ugliness.

In researching this topic, I found myself moved in two directions. I’m now more certain that there is an objective basis for Beauty. The historical and empirical evidence is clear on that. At the same time, I can’t shake that there’s still a degree of personal taste that is not only undeniable, but necessary. If all art, buildings, and people needed to look exactly alike to be called Beautiful, there would be no point in making new art or meeting new people at all.

I’ve also encountered many more questions. Where do we draw the line between beauty and fashion (with which we remain obsessed)? What does Beauty look like in men? Do women agree with men on what is beautiful in women? Given that men have historically held the dominant role politically and culturally, do we have a full or accurate picture of Beauty from all perspectives? These are all interesting questions, and I’m sure you (dear reader) have many more, so please share them below. Perhaps I’ll write more on this topic in a future post.

To conclude: I believe that the pursuit of Beauty is not only preferable, but necessary to the flourishing of human society. Right now there is a general feeling that our culture is in a dire state; no doubt the solution is complex and multi-faceted, but to my mind, re-orienting ourselves toward to elevation of Beauty can only be beneficial. The reason is simple—Beauty never denigrates. It only uplifts. If we can once again surround ourselves with Beautiful things, and aspire to be Beautiful within ourselves, the virtues this inspires—honesty, goodness, courage, charity, hope—might return as well. Time will tell.

Impressive, but far from the most impressive classical/neoclassical work. What makes the Stormont building such a good comparison here is how subdued it is. It’s relatively unremarkable, and yet compared to the Scottish building, an architectural marvel.

There is research to support this, of course, but here’s something even more compelling: upon asking my 10-year-old stepdaughter which of the two buildings she preferred, she immediately chose the first, describing the Scottish building as “trash” and “like a construction site”. Clever girl!

I’m not suggesting that this is an original idea proposed by Lesko, but the ideas espoused in her essay are (to my knowledge) fairly representative of those held by most contemporary feminists.

Marilyn was a natural red-head, of course, but we won’t fault her for that.

Much is made of the apparent preference for plumpness during the Tang Dynasty, but this seems to have been related more to a desire to reverence or imitate the ruling class at the time, who were from a lineage of more opulent, meat-eating steppe peoples. Power and status can certainly influence beauty standards in the short term, but in the long term, the traits pushed by those in power need to actually be beautiful. Otherwise, as we see in China after this period, the true ideal eventually re-emerges.

Little et al., 2011, p. 1640.

I enjoyed this essay very much and found it to be persuasive.

I have two comments.

I thought of the Golden Ratio when you mentioned the attraction of things found in nature.

I thought as well that as I've aged I've found more mature women more beautiful. Perhaps it's because I'm no longer looking for a child bearing mate and so when I see a woman (like my wife of 38 years) who carries her maturity and her beauty in one inseparable piece, I find that more beautiful than a twenty something year old. It's an interesting question, and I wonder if that shift is typical. I also wonder if women shift their ideals of a beautiful man as they grow older.

What a fantastic essay. Thank you for sharing these thoughts. Beauty is indeed something that uplifts, and something we need to recapture in our lives in this modern world. People behave differently depending on the beauty in the environment. Beauty calls us to a higher plane of existence.

One thought on beauty definitions being oppressive for women. As a woman, I will say that for me personally, it is not a definition of beauty or a culturally informed beauty ideal that is oppressive. In ancient cultures, if you were a working class woman in the fields, your skin was dry and cracked and darkened, you wouldn't dream of a world where you compete in a beauty contest on Instagram. Beauty (capital B) was a luxury of kings and queens. (I like how you referred to capital B Beautiful and lowercase b beautiful.) We working class women are not barred from any measure of beauty (lowercase b), but our beauty is a pale image of the radiance that is possible---something that leads us to stretch our vision beyond ourselves.