“Quid est Deus? Mens universi.”

When I was a child, my mum would use car trips as opportunities to have serious discussions. I think it was a way to force conversations that she knew I didn’t want to have. How babies are made, how I needed to help out more around the house, how I needed to find a girlfriend who wasn’t so high maintenance… in retrospect, it wasn’t a bad strategy. For the fifteen-or-so minutes it took to get from our place to the local shops, the conversation was going to happen whether I liked it or not.

Every so often I flipped the script. My topics were more philosophical—e.g., “Hey mum, what happens after we die?”, “hey mum, what if we’re all just characters in God’s dream?”—and while I don’t remember many of her responses (sorry mum), no one actually knows the answers to these questions, so it probably doesn’t matter too much. What matters is the questions themselves, and the fact that this ten-year-old kid was starting to ask them.

“Today a young man on acid realised that all matter is merely energy condensed to a slow vibration; that we are all one consciousness experiencing itself subjectively, there is no such thing as death, life is only a dream, and we are the imagination of ourselves. Here’s Tom with the Weather.” - Bill Hicks

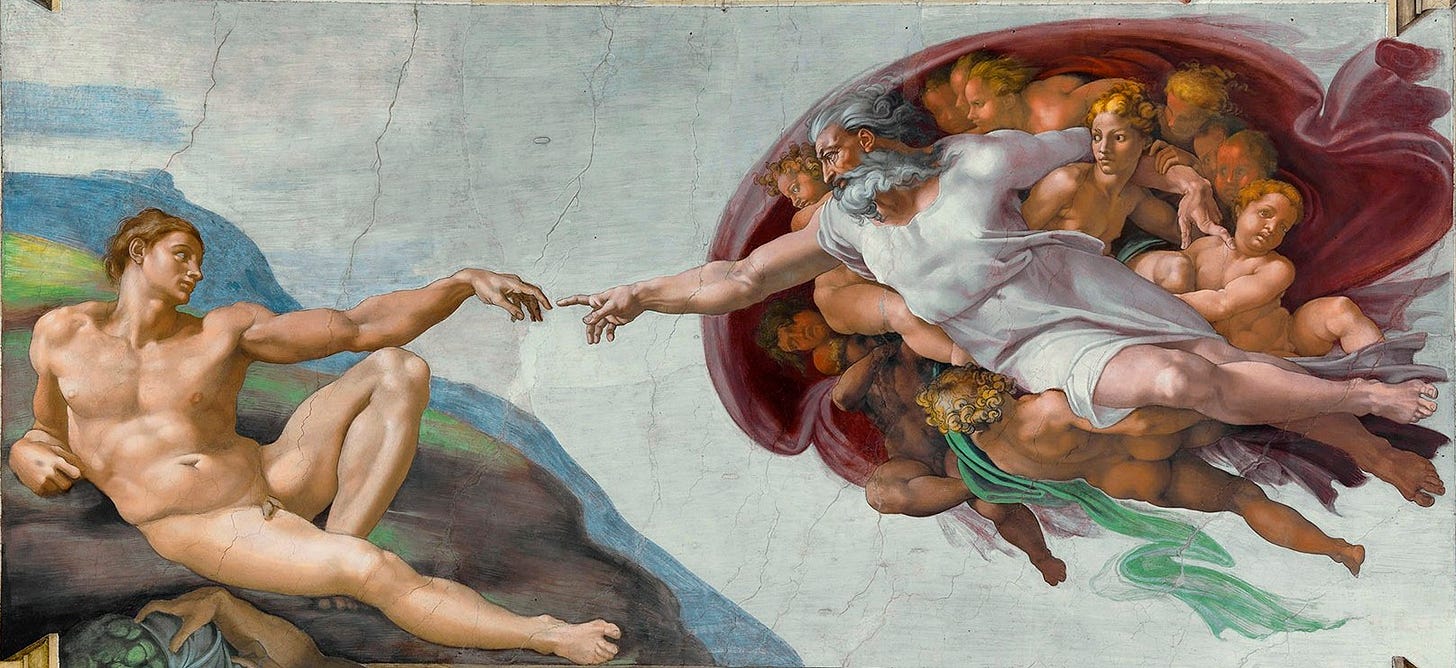

But that second question has always struck me. Where did I get the idea that God can dream? And why would we all be in it rather than outside of it? I certainly didn’t learn that in school. Twelve years of Catholic education taught me nothing about God’s nature except that He was exactly as The Simpsons portrayed Him: an old bearded dude, a tangible being who lived ‘up there’, someone who expected blind obedience and punished minor transgressions. It’s no surprise that I left school a committed atheist. It’s no surprise that I was so easily persuaded by figures like Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens. Their arguments were the logical conclusion of a reductive Materialist worldview that my teachers had failed to debunk. It’s worse than that, actually—my teachers were the ones who taught it to me.

So what’s the alternative? The Word; the eternal Logos. It’s easy to hold the Materialist perspective when it’s all you’ve ever known, but in truth, most of the great thinkers throughout history have defended some version of what we now call Metaphysical Idealism. That is, the fundamental substance of reality is not matter, but mind—spirit, consciousness—what philosophers call the Logos, and what theologians actually mean when they talk about God. God, being infinite spirit, is neither a finite being within reality (He is not ‘an old bearded dude’), nor is He separate from it (He is not ‘up there’). God is the source; reality flows from and in Him. This means that we truly are all part of God’s mind, only God does not have a mind, but is mind, just as He is not a being, but is Being itself (per Aquinus, ‘ipsum esse subsistens’). That curious ten-year-old wasn’t far off the mark.

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things were made through Him, and without Him nothing was made that was made. In Him was life, and the life was the light of men.” - John 1:1-4, NKJV

“All things come to pass according to the Logos.” - Heraclitus

One of the key differences between us and God is that we are finite. We exist within reality (we are beings), but we are not reality itself (we are not Being). Even so, we seem to play a particularly important role in all of this. As far as we know, God doesn’t speak to tigers and willow trees, and they don’t build cathedrals to Him. So why are we different? What makes us so special? To put it another way: what does God lack that we offer?

The standard answer to this question is nothing. God, in His perfection, lacks nothing. He doesn’t need us. This is correct, I think, given that we exist in and through God. After all, anything that we could offer God is only possible through Him. But this answer misses something important. One of the defining features of our species—what separates us from tigers and willow trees—is our ability to ask questions, to reflect on the nature of reality. In More Than Allegory: On Religious Myth, Truth and Belief, Idealist philosopher Bernardo Kastrup suggests that, if all of reality is mental rather than physical, our unique capacity for reflection might be the very purpose of our existence. This idea is best expressed in a scene from Kastrup’s own ‘modern myth’, wherein the protagonist meets a character he calls the Other:

‘Do you know everything?’ My interest in the Other was directly proportional to how much I thought he knew.

‘Potentially yes, but I only truly know what you or another living being asks me.’ […]

‘So before I or someone else asks you a question,’ I insisted, ‘even you don’t know the answer?’

‘I do know the answer always, but only in potentiality. In other words, I know it, but I don’t know that I know it. The answer remains latent, like the light of a non-ignited match, and doesn’t illuminate my experience; or yours.’

This was fertile ground and my thoughts were running wild:

‘Why don’t you ask yourself all relevant questions? You could then illuminate the whole of existence and eradicate ignorance!’

‘Because I am incapable of asking myself questions. […] Asking myself questions would require a particular cognitive configuration that arises exclusively within clusters like the human mind. Only the dense internal associations of a cluster enable one layer of cognition to become an object of inquiry to another layer of cognition. In other words, they enable you to think about your thoughts. And only by thinking about your thoughts can you formulate the probing questions required to make sense of existence. The reason is that all reality is in mind. Therefore, to understand reality one needs to inquire into the multiple subtle layers of hidden assumptions, expectations, and beliefs in one’s own mind. To do so, mind must turn in upon itself. ’ […]

‘This is the meaning of life! The human purpose is to light up the match of your latent knowledge!’

‘That’s a fair way to put it…’

The Other is clearly Kastrup’s substitute for God. Through the Other, Kastrup makes an interesting claim: that God cannot ask Himself questions, meaning that He is unable to self-reflect. This is quite an assertion, but it’s not unfounded; God doesn’t ask these kinds of questions anywhere in the Bible. He asks questions that invite moral reflection and deeper connection from His followers, but He does not (or will not, or can not) ponder over His own nature.

Now, let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Kastrup’s books are interesting, but they’re not the Bible. We shouldn’t take them as Gospel. But if we really are ‘called to know God’, at some point in that process we’re going to start asking why, and maybe this is it. George Berkeley famously concluded that ‘to be is to be perceived’, meaning that to exist at all, we must logically exist in relation to something else that perceives and acknowledges our existence1. Maybe our role in God’s grand plan is just this, to be His perceivers. It’s not that God can’t self-reflect; rather, we are the tools he uses to do so. “We are all one consciousness experiencing itself subjectively” might sound like hippy nonsense, but that doesn’t mean it’s incorrect.

“I know the resurrection is a fact, and Watergate proved it to me. How? Because 12 men testified they had seen Jesus raised from the dead, then they proclaimed that truth for 40 years, never once denying it. Every one was beaten, tortured, stoned and put in prison… Watergate embroiled 12 of the most powerful men in the world and they couldn't keep a lie for three weeks.” - Charles Colson

Here’s a fun question to ask your priest: “How did Jesus rise from the dead?”

One of the virtues of Metaphysical Idealism is that it offers an explanation for certain dubious but well-attested events, such as the resurrection of Jesus. Consider: under Materialism, physical death is all there is. Mind emerges from matter, so without a body, there can be no consciousness. Under Idealism, however, matter emerges from mind. This means that consciousness extends beyond matter, so an individual soul can theoretically live on after the death of its body.

We don’t have a good scientific theory to explain Jesus’ resurrection (yet), but in Kastrup’s view, there are multiple ‘layers’ of the universal mind (the Other, or God), and physical laws are held at a deeper layer of this mind, one that is currently inaccessible to us. Jesus, being the avatar of God, had the power to access and alter the laws of reality at this deeper layer. This allowed him to cure diseases, walk on water, and in his final moments, even deny death itself.

If Kastrup is correct, this deeper layer is as much a part of reality as anything else, so scientific advances could one day grant us access to it. We might even develop tools to modify the source code of the universe, and thereby achieve immortality (a kind of technological theosis). Incidentally, I think this would be a mistake2. We were never meant to achieve physical immortality, and unless this is God’s plan, I think we would live to regret it. But we split the atom, so who knows how far we’ll go? We might just meet our maker.

To sum up: God exists, but He’s not what we think He is; He invites us to participate in His existence, but we’re hubristic, so in the end we’ll probably just mess it all up (as we always do). Maybe this is why forgiveness is so central to the Christian faith. God doesn’t set arbitrary rules because He likes to punish us for breaking them—quite the contrary. The rules of a well-ordered universe, like God Himself, are what they are, and in His mercy God offers us a corrective for when we defy them.

This is all just educated speculation, of course. Who can truly know the mind of God? But there’s a logic to it, and I’ve found these ideas incredibly valuable in my own spiritual journey. Perhaps they will be of some use to you, too. If not, feel free to ignore them.

“And what is God? The universal intelligence. What is God, did I say? All that you see and all that you cannot see. His greatness exceeds the bounds of thought. Render Him His true greatness and He is all in all, He is at once within and without His works. What, then, is the difference between the divine nature and the human? In us the better part is spirit, in Him there is nothing except spirit.” - Seneca the Younger

By way of analogy, if a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, the tree never existed at all.

Consider: "Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic." Consider, too, that we might already be using magic, and the Bible condemns this. Why? See Genesis 11:1-9 and Kaczynski (1995).

Love the development of these ideas since our conversation. I’ve been thinking about Kastrup’s own fixation on suffering in the world. Both manmade horrors like the war in Ukraine and nature itself (how many animals go peacefully?).

I suspect being hung up on the problem of evil is a misunderstanding of the nature of the universe (ie, God). I don’t really have an answer for evil, but view that as my own limited view.

If God isn't able to be self-conscious how or why would He create beings who can be self-aware or ask questions, and so forth? This seems to be just another way of formulating the current belief that humans are lumps of protoplasm brought into being by per chance.