Essay Club: Myth, History, and Pagan Origins by John Michael Greer

"Human beings are incurably mythic creatures."

Welcome back, and happy new year! In our final Essay Club of 2023, we discussed Vernon Lee’s In Praise of Silence, which prompted lots of interesting discussion (and even a poem). I’m excited to kick 2024 off with an essay by John Michael Greer called Myth, History, and Pagan Origins, which I thoroughly enjoyed. If you’re a regular reader of Mind & Mythos, you should have no trouble with this one. Greer’s writing style is very accessible, and the essay itself takes only about 15 minutes to read. Let’s begin!

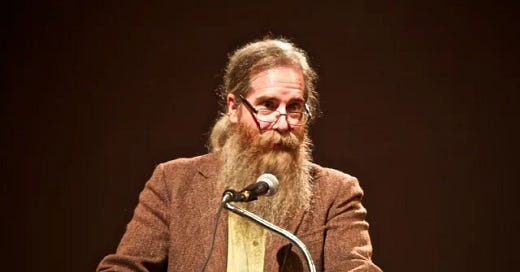

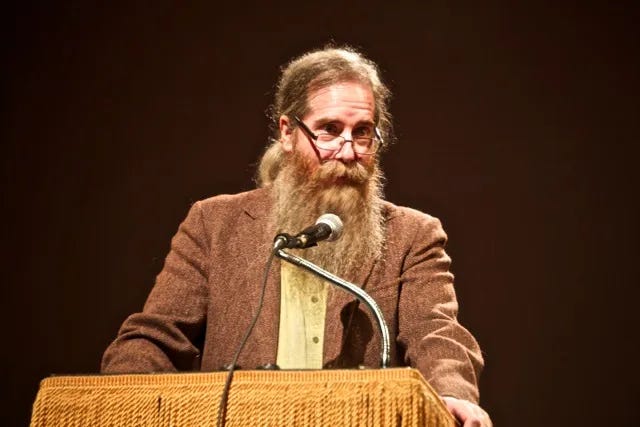

John Michael Greer (born 1962), Grand Archdruid Emeritus of the Ancient Order of Druids in America, is an American writer, occultist, and druid. He’s written over 40 books on topics related to occult spirituality, as well as numerous books and essays on history, economics, politics, technology, and ecology. He’s also an accomplished writer of fiction novels, many of which are based in the Cthulhu Mythos.

You may giggle at the concept of ‘druidry’, but Greer is quite serious, and his work is worth taking seriously. He’s a thoughtful and intelligent writer, and he has a strong foundation in the Western philosophical tradition. Greer is also fairly active online—if you enjoy this piece, I highly recommend following his work at Ecosophia, or catching one of his interviews on Youtube. He’s a regular guest on the Hermitix podcast, which is a great podcast in its own right.

Myth, History, and Pagan Origins is Greer’s response to a longstanding debate within the Pagan community on the origins (historic and mythical) of their movement. This may seem a tad obscure, but it’s really about much more than this, and may well be my favourite essay of those we’ve covered so far. Read on to learn more about Greer’s perspective on history, myth, ideology, and the implications of some of our most deeply held beliefs.

Myth, History, and Pagan Origins (1999)

Greer begins his essay with an observation: in debates about the origins of modern Paganism, discussions tend to be framed in terms of historical fact—for example, what did or did not happen, which figures did or did not exist. In Greer’s opinion, this is a mistake. What modern Pagans should instead be exploring are “questions of validity, of meaning and of ultimate concerns… not questions of history, in other words, but of myth.”

These kinds of topics are difficult to discuss in our modern society. We’ve been taught to interpret myths in a particular way, as Greer explains:

“To most people in modern Western societies, the word ‘myth’ means, simply, a story that isn’t true… The word ‘history’, in turn, is treated as an antonym of ‘myth’, and thus a synonym for ‘truth’ — or at least of ‘fact’. Myths are stories about events that didn’t happen, in other words, while history is what did happen. […]

That attitude comes out of the ideas and definitions of truth that came into fashion in the West around the time of the Scientific Revolution – ideas that restrict the concept of truth to the sort of thing that can be known by the senses and written up in newspaper articles.”

In short, to the Western mind, a myth is something that is untrue, and a historical event is something that is verifiably true. The problem with this distinction is that it leads to a wholesale rejection of mythology (the study of myths), and in rejecting mythology, we deprive ourselves of a proper understanding of what actually feeds our beliefs and values. With this in mind, Greer offers an alternative, more traditional perspective:

“Myths can be made out of events that happened, of events that never happened, or a mixture of both. I propose that it’s not the source that defines something as myth, but the function; not whether the thing happened, but whether it is – whether it goes beyond the merely factual into the realm of meaning and ultimate concern, of the deep patterns of interpretation through which people comprehend their experience of the world.

Myths, according to this understanding, are the stories groups of people use to teach themselves about who they are and what the world is like.”

Myths are the stories people use to teach themselves about who they are and what the world is like. Their relevance and ‘truth’ depend not on historical accuracy, but on whether they speak to us on this deeper level. The challenge with these kinds of mythic stories is that they can’t be verified. Their truth depends on our subjective experience of them, so they force us to sit with a level of uncertainty that can be difficult to handle. Alternatively, people can become too wedded to their myths, even in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

Either way, we’re far more comfortable with the certainty offered by historical narratives and scientific theories, even if this is (as Greer notes) an illusory certainty:

“Human beings are incurably mythic creatures. Take away myths from a group of people, and they will quickly construct new ones; demand that they believe facts rather than myths, and they’ll construct their new myths using facts as the raw material.”

It’s not that fact-based narratives are bad or wrong. Greer acknowledges that factual accuracy has its place. But we delude ourselves if we think our contemporary histories and scientific theories lack a mythical element. When selecting stories, facts, and data to construct an ‘objective’ historical narrative, the historian necessarily selects material that fits the story he or she is trying to tell. Without an awareness of this, the historian is likely to dilute his supposedly objective historical narrative with a variety (a diversity, even) of modern mythical ideas. If nothing else, it makes for bad history.

So myths are important—“they shape consciousness, and therefore they shape behavior”—and even at our most objective, there’s no escaping them. Better to take them seriously, then, and develop a deeper understanding of our own modern myths. What are these myths, and what impact have they had on Western society?

Greer identifies the Myth of Progress (the idea that “progress has taken place, that we are experiencing the results of past progress, and that[…] progress will continue in the future”1) as one of the primary myths of our era. He then identifies the Myth of Moral Dualism as another, one that is apparently quite prominent amongst modern Pagans. The Myth of Moral Dualism is essentially a myth of good versus evil—we are the virtuous oppressed, they are the evil oppressors—and in all versions of this myth, there is a promise that some day the virtuous will be restored to their rightful place atop the hierarchy. Greer provides several examples, including the pagan myth (good pagans vs. evil Christians), the Communist myth (good Commies vs. evil Capitalists), and the Christian one (good Christians vs. evil Satan worshippers). No doubt you can think of others—good BIPOC vs. evil white colonists, good psychodynamic therapists vs. evil CBT practitioners—but in all cases this is a “myth of war”, with the implication that neither can live while the other survives.

It seems to me that many of the cultural and political problems we currently face are rooted in these mythic ideas. The eternal march of progress, the endless struggle against perceived oppression—where does it lead us all? To war, apparently. Right now it’s a war of the spirit, of culture and politics, but in the long run the fulfilment of these myths necessitate armed conflict. And why not? To let evil triumph—for good men to do nothing—is unacceptable. Whether or not the facts fit the myth is irrelevant when faced with such a powerful narrative.

But maybe there’s another path. By reevaluating our myths and considering others, it might be possible to rewrite this story. Greer offers one possibility:

“Imagine a Pagan version of the myth that eliminated these features – that presented the relation between Paganism and Christianity (or patriarchy, or whatever) as a creative balance between equally positive forces; that saw, let’s say, the two of them as incomplete without each other, or forming some kind of greater whole in their union…”

Perhaps our enemies are not so unreasonable. Perhaps we can find a way to stop fighting and write a new myth, one that sees us working together toward a greater good. Honestly, I’m not optimistic. The in-group vs. out-group story is hardwired into us—it keeps us alive—and until we encounter real-life aliens, other humans will remain our greatest threat.

I do think it can change, though. It’s happened before. In Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morality, he lays out how Western morality changed from a ‘good vs. bad’ narrative (good = noble, beautiful, successful, wealthy, etc.; bad = low-born, ugly, unsuccessful, destitute, etc.) to our current ‘good vs. evil’ (oppressor vs. oppressed) one. This is a bit beyond the scope of this discussion, but it’s worth noting that mythic change has happened at least once, so could probably happen again.

Let’s finish up.

Questions and Essay Selection

What did you all think of John Michael Greer’s Essay? Here are a few questions to mull over:

How does Greer’s writing style compare to that of some of the other authors we’ve read? Is it more Vernon Lee or George Orwell?

What do you think of Greer’s main thesis? Is myth more important than history to our overall understanding of ourselves and the world?

Where have you noticed these mythic themes—the Myth of Progress, the Myth of Moral Dualism—in real life?

Is it possible to have a foundational myth without an in-group/out-group dynamic? What might this look like?

As always, please share your own thoughts and questions in the comments. If you enjoyed this, I’d also love it if you’d share this around and subscribe (if you haven’t already done so).

And of course, Essay Club continues! We’ll reconvene in a fortnight to discuss Christopher Hitchens’ Fragments From an Education. A very different thinker, and a very different topic. I look forward to discussing it with you all.

Before you go, don’t forget to vote for the next Essay Club pick below (you can also suggest others in the comments):

The Myth of Progress (PDF) by Theodore L. Shay

A relevant follow up to Greer, this essay places the ‘Myth of Progress’ in its historical context.

A Reconception of Destiny by Dawson Eliasen (Orbius Tertius on Substack)

Dawson’s review of The Soul’s Code by James Hillman. Here he reflects on the concept of the ‘daimon’, one’s calling or destiny, and how intentional myth-making can help us to craft and realise our destinies.

The Death of the Author (PDF) by Roland Barthes

A classic of literary criticism. In this essay, Barthes argues that literary works should not always be read with the author’s intention in mind—sometimes more can be discovered by discarding this single interpretation.

The Narrative Microbiome by Heliotroph (Heliotrophy on Substack)

Heliotroph introduces the concept of a ‘narrative microbiome’, the “selection of stories and logics that a person has absorbed and integrated into their own mental functions”. He suggests that our current narrative environment is not a healthy one, and provides a model for how we can fix this.

Shay, 1957, p. 5. Here ‘progress’ tends to refer to some ambiguous combination of technological and moral progress, and generally involves the rejection and/or overthrowing of traditional religious beliefs, societal norms, etc.

I like how Greer encourages us to examine the premises or cultural currents that undergird our belief systems. I don't think the myth of moral dualism is inherently flawed. Yes, history has demonstrated terrible abuses of the us/them groupthink, but going with the spirit of examining myths rather than ignoring them, perhaps the us/them theme (with humanitarian guardrails) provides a way to foster a sense of identity. Clear boundaries of this is me and this is you doesn't need to lead to war. I think his suggestion of two belief systems becoming incomplete without the other actually erases identity, and if humans have craved a sense of identity from the beginning of storytelling time, then it seems unrealistic to try to remove that. Instead, fostering an understanding of our differences and a celebration of each other with an acknowledgement of differences seems a more feasible goal. But maybe I'm wrong---maybe people out there want to meld together into one happy mutually compatible belief system where no one is right or wrong.