Essay Club: The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment by C. S. Lewis

"A tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive..."

Welcome back to Essay Club! Last time we discussed George Orwell’s Why I Write, a classic in the essay genre. Today we’ll be discussing The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment by C. S. Lewis. If you haven’t read it yet, I highly recommend you do so. It’s great, and it won’t take you more than 10-15 minutes.

If you’re short on time, though, don’t worry—I’ve got you covered. I’ll summarise Lewis’ thoughts here and provide my own commentary as I go.

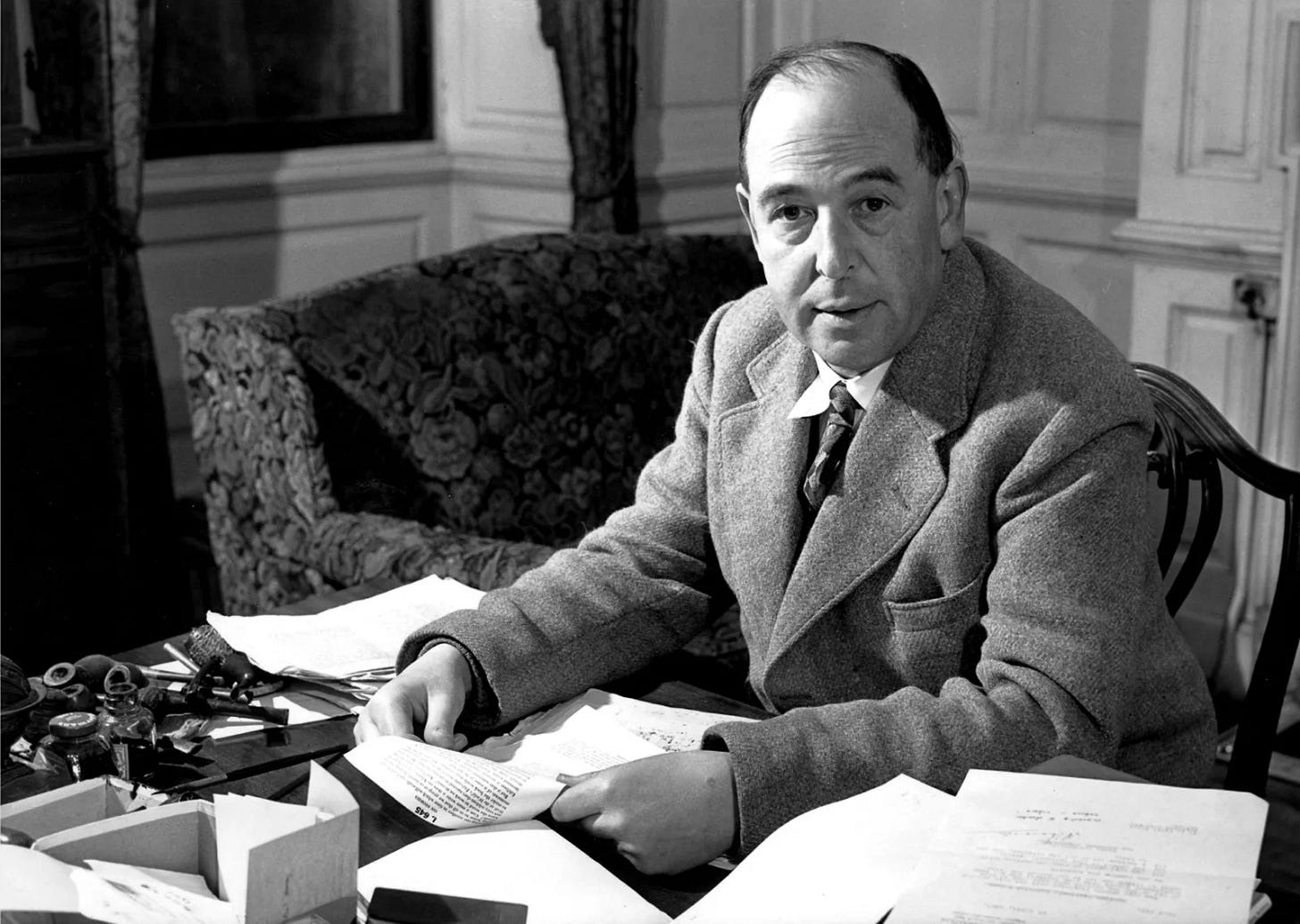

Clive Staples Lewis (1898-1963) was a British writer, literary scholar, and Christian philosopher/apologist. He is best known as the author of The Chronicles of Narnia, as well as The Space Trilogy and a variety of non-fiction works such as Mere Christianity and The Abolition of Man. I’ve always enjoyed Lewis’ style; he wrote in a very accessible, matter-of-fact way, while never shying away from some of the most difficult theological and philosophical topics. In The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment he discusses an issue that is arguably even more relevant now than it was in his day: retributive versus restorative justice.

The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment (1954)

Lewis begins by positioning himself firmly against what he calls the ‘Humanitarian theory of punishment’, which holds that:

“To punish a man because he deserves it, and as much as he deserves, is mere revenge, and, therefore, barbarous and immoral… the only legitimate motives for punishing are the desire to deter others by example or to mend the criminal.”

For Lewis, the problem with this idea is that a punishment handed down by a judge can only be deemed just if it is deserved—that is, if it could be deemed by a reasonable person to be appropriate and proportionate to the crime committed. By removing desert (deservedness) from the equation, the concept of justice is also removed. As for deterrents and cures:

“We demand of a deterrent not whether it is just but whether it will deter. We demand of a cure not whether it is just but whether it succeeds. Thus when we cease to consider what the criminal deserves and consider only what will cure him or deter others, we have tacitly removed him from the sphere of justice altogether; instead of a person, a subject of rights, we now have a mere object, a patient, a "case".”

The question to be asked about a punishment, then, changes from “is this just?” to “does this work (to deter or cure)?”. It becomes a question for psychologists, not jurists or judges. And therein lies the problem—while the convicted man will still be mandated to undergo whatever punishment is owed him, under a ‘Humanitarian’ regime the nature of that punishment becomes something very different. It would no longer be a clear and finite number of [dollars owed, years in prison, lashes], but ‘until the patient is cured’, or ‘until the patient is deemed fit for society’, which may never happen. We all have within us a sense of what kind of a punishment would be just for different kinds of crimes, but we cannot—indeed, are not qualified to—have an opinion on whether a deterrent or cure has been successful.

Turning to deterrents specifically, Lewis suggests that the reasoning for this is even more concerning:

“When you punish a man in terrorem, make of him an "example" to others, you are admittedly using him as a means to an end; someone else's end. This, in itself, would be a very wicked thing to do. On the classical theory of Punishment it was of course justified on the ground that the man deserved it…. But take away desert and the whole morality of the punishment disappears. Why, in Heaven's name, am I to be sacrificed to the good of society in this way?—unless, of course, I deserve it.”

But it gets worse. Without the concept of desert, we are led to a clear logical conclusion: “it is not absolutely necessary that the man we punish should even have committed the crime”. As long as the message gets across, as long as the masses are deterred from engaging in certain acts, why should it matter who stands in as the scapegoat? There is a sound Utilitarian justification for it, and “every modern State has powers which make it easy to fake a trial”. Our own rulers are hardly so virtuous that they’d shun such methods if they could get away with it—they are, in Lewis’ words, “fallen men… neither very wise, nor very good”.

Lewis is not entirely cynical, of course. He recognises that the Humanitarian position is usually based in a desire to do the right thing, and it’s only through the consistent logical application of Humanitarian policies that such an outcome could eventuate. But as history repeatedly shows:

“Of all tyrannies a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive… those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience.”

And as we turn from a system in which there are fair and reasonable consequences for bad behaviour to one that treats such behaviour as a disease to be cured, we need to pay particular attention to what we start to call a disease. As a Christian, Lewis expresses his fear that religiosity may come to be seen in this light, and “it will not be persecution. Even if the treatment is painful, even if it is life-long, even if it is fatal, that will be only a regrettable accident; the intention was purely therapeutic”. I’ve mentioned elsewhere the historic inclusion of homosexuality in earlier iterations of the DSM1, and this is a perfect (if somewhat ironic) example of the sort of thing Lewis means.

What are we to make of all this? I think Lewis’ core argument is right—punishment of criminal behaviour is a good and necessary function of society, and for punishment to be worth anything at all, this must be just punishment. Sentences need to be passed in accordance with what is deserved, not some other arbitrary measure. But I think to reject deterrent or curative methods entirely would be a mistake. It can be difficult (and expensive), but there is no reason why we shouldn’t aim to both punish bad behaviour and attempt to cure or deter someone from future crime. Some people cannot be cured or deterred, and this must be considered, but a system that only punishes merely perpetuates itself, as it offers no way out for those with the desire to do better.

Questions and Housekeeping

Question time! As always, you’re welcome to pose your own questions in the comments, but here are a few to consider:

What did you think of this essay, generally? Intellectually, aesthetically, morally?

Do you agree or disagree with Lewis’ main point? Is it possible to have a just system without consideration of what is deserved?

What did you make of the rhetorical strategies employed by Lewis in this essay? Were you persuaded? Did they put you off?

If you weren’t already familiar with it, did reading this essay change your view of Lewis and his work?

Essay Club is a fortnightly affair, so please join me in two weeks to discuss The Origins of Cognitive Thought by B. F. Skinner. This essay was by far the most popular of the three options, and it’s sure to be an interesting one. See you soon!

If you enjoyed this, please consider sharing it around and subscribing to Mind & Mythos:

And if you want to see this continue, please share your own essay suggestions in the comments, and vote for the next pick below:

Religion, Heuristics, and Intergenerational Risk Management (PDF) by Rupert Read & Nassim Nicholas Taleb

A proper understanding of religion through the lens of rational philosophy—not a collection of senseless rituals, but a set of practices that emerged to provide quick rules for good living and protection against intergenerational risks.

In Praise of Silence by Vernon Lee

An essay in defence of the comfortable, familiar silence. Written by Vernon Lee, the pseudonym used by writer Violet Paget. I suggest reading this one on your mobile browser—the desktop website is a horror of web design.

My Own Life by David Hume

A brief reflection on life as a writer and philosopher, written by one history’s greatest thinkers. Thanks to Jonah Dunch for the recommendation!

The Most Precious Resource is Agency by Simon Sarris

On the importance of cultivating agency in our children. A short but very good essay written by Substack local Simon Sarris.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, one of the manuals used by psychiatrists and psychologists to diagnose mental disorders.

This is a humdinger of an essay. Wonderful, intellectual food. I'm taking my time responding to this one because the contents are important and as relevant if not more today than they were when it was written. That's what I think of the essay. This is brilliant argumentation, brilliant writing. The union of moral consideration of man with civic justice is important and he walks the line very well.

Do I agree? Yes. I believe all authority flows to man from God. That means it sits on the apparatus of government before it reaches us, and that our nobility qua creations of God cannot be subdivided from our responsibility qua citizens and subjects. This is the tension CS Lewis is exploring--what happens when we stop treating man as having an inherent dignity qua creation, and start treating him as only deserving dignity conditionally if he obeys the law. If he doesn't, he abrogates all his rights to humanity and can be whisked away to be treated, punished, etc. CS Lewis avoids some of the hard rubber-meets-the-road discussion by disclaiming in the first paragraph that he's not talking about that. Which is fine, that's not what he was arguing. But there's a good argument to be had there, too.

Rhetorical Strategies: I was persuaded, TBH on first read I couldn't tell you which strategies he used, probably due to my own confirmation bias. He was speaking a language I know how to speak and he simply and forthrightly laid down his arguments using the parameters which I have already heard and understand. However, if I was to look at this from an antagonistic point of view: probably my biggest argument against Lewis would be "What do you propose?" And that's where Lewis avoided controversy by his disclaimer in the first paragraph. He is arguing against something, not putting forth an argument for something. Is the death penalty just? Is imprisonment just? What is the justice system *supposed to do*??? Lewis doesn't touch that with a ten foot pole, and that's the more practical problem. The philosophical problems are important and certainly prior to the practical problems, but there are people *right now* in jeopardy and arguing philosophy doesn't help them. So that's the approach I would take if I was positioned opposite Lewis: What should we do *right now*?

I was not already familiar with this essay, but this to me seems a much more argumentative side of Lewis than I had encountered before. It was fun honestly. I read the essay out loud to myself because it's the morning and I needed help to stay focused--and I found myself getting fired up. There's some excellent zingers, and I don't associate Lewis with rhetorical spiciness, I always consider him level headed though very very clever.

This was great. You might have seen the note I posted, but I want to reiterate: You are doing a GREAT service with this essay club, and it is one of my new favorite things on substack. Thank you very much for doing this!