What the DSM-5 Gets Wrong About Mental Illness

Discussing the flaws of DSM-5 and how to solve them. On Personality and Psychopathology, part 2

In part 1 of this series, I introduced several theories that together explain how and why humans think and act the way they do. In this post, I want to explore the ‘dysfunctional’ side of human experience. Let’s talk about mental illness.

Mental illness, or psychopathology, is a breakdown in ordinary psychological functioning which causes marked distress or impairment. Psychopathology has long been understood in terms of diagnostic categories, outlined in manuals such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (currently in its fifth edition; DSM-51), which categorises mental disorders on the basis of observed or reported symptoms—cognitive, behavioural, and emotional abnormalities. Put simply, if a person experiences a certain number of symptoms (and consequent distress or functional impairment) they’ll meet criteria for a diagnosis. For example, under DSM-5 criteria, Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) requires five of a possible nine symptoms to be present for a period of two weeks, including low or flat mood, and/or diminished pleasure or interest in typically enjoyed activities.

As a mental health clinician, I find diagnostic labels very useful. They make it easier to understand the problems a person is experiencing and why, and they guide me in planning how best to help them. However, the categorical approach has received substantial criticism, and there is now a strong case to be made that it’s no longer viable. It could take another five DSM-sized books to list every criticism ever made of the DSM, so I won’t go too in depth on this—but before I can offer what I believe is a better alternative, let’s first discuss some of the main problems with the DSM-5.

Problems With the DSM-5

Humans traits are rarely binary

As models like the Five Factor Model (FFM; see my previous post) show, human psychology is typically not a matter of being one way or another. We are not either extroverted or introverted; we are not either neurotic or stable. In reality, human traits are more like sliding scales. We can set arbitrary cut-points to place people in one box or another, but people will vary a great deal depending on various day-to-day factors. Psychopathology is no different. We may feel more or less anxiety on a particular day, and some of us might experience it quite strongly, but no one goes through life without experiencing any anxiety at all. The categorical approach to psychopathology misses this nuance. By saying a person either does or does not meet criteria for a particular diagnosis, many people whose problems fall just below this threshold go unsupported. Others for whom a diagnosis is only temporarily appropriate might be put on medications that are at best expensive and unnecessary, and at worst actively harmful, with side effects such as weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and memory impairment.

Diagnostic ‘blurred lines’

As any mental health clinician can attest, if a person has a mental disorder, they’re likely to also show ‘co-morbid’ symptoms of other disorders. Researchers have suggested that this is “the rule, rather than the exception”, estimating that over 50% of people with a mental illness will meet criteria for at least one other diagnosis. There appears to be something like a general neurotic tendency that accounts for symptoms of anxiety, depression, and other related issues; this suggests that these seemingly distinct disorders may actually be different expressions of the same underlying problem, perhaps varying due to different internal and external factors.

A related problem is seen in the use of symptom counts to diagnose mental disorders. Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) provides a useful example. For a diagnosis of BPD, a person must show at least five of a possible nine symptoms - this means that two individuals could meet criteria for the same diagnosis with only a single overlapping symptom. If two people with the same diagnosis present in almost entirely different ways, what sense is there in giving them the same label?

With so many ‘blurred lines’ between and within diagnostic categories, it is difficult to take seriously the idea that diagnostic labels accurately represent the phenomenon of psychopathology.

Pathologising of ordinary human behaviour

Some critics have argued that healthy behaviours are sometimes labelled as ‘disordered’ simply because they don’t fit our culture-bound vision of normal behaviour. The most famous example of this, of course, is homosexuality. As late as DSM-III, homosexuality was classed as a ‘sexual deviation’, and could be treated by psychiatrists as a form of psychological dysfunction. It was removed from later editions in response to mounting pressure, but the problem arguably still remains in other areas. Consider Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), often first suspected on the basis of a child’s classroom behaviour or performance. Is it reasonable to expect a child to sit quietly and study for up to six hours per day? Obviously ADHD is a real phenomenon, and we need to take seriously those who struggle with it. But in my own clinical experience, this is a disorder that is now grossly over-diagnosed.

Returning to the point—it’s important that we take our own cultural biases into account before we pathologise what may be natural human behaviour. While the presence of bias and stigmatisation alone are not enough to suggest that a diagnostic category is incorrect, we need to be careful about labelling harmless behavioural quirks as problems.

Searching For a Solution: The HiTOP

These criticisms aren’t new. The DSM has been under fire since its first publication in 1952, and dimensional measures of psychopathology have been around for almost as long. Without a comprehensive and evidence-backed alternative, however, the DSM has remained the reference manual for psychiatric diagnosis.

This began to change in 2013. The publication of DSM-5 saw significant backlash, and one influential organisation—the US National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)—publicly expressed dissatisfaction with the manual. They began to encourage (and fund) research centered around the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC), a more biologically-based approach to understanding psychopathology. In 2017 another large research group, the HiTOP Consortium, introduced their own model, the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP), which offers an empirically-based approach involving methods similar to those used to uncover the FFM. These are quite distinct approaches, but not necessarily opposed. In time, I suspect there will be convergence on a mutually agreeable model.

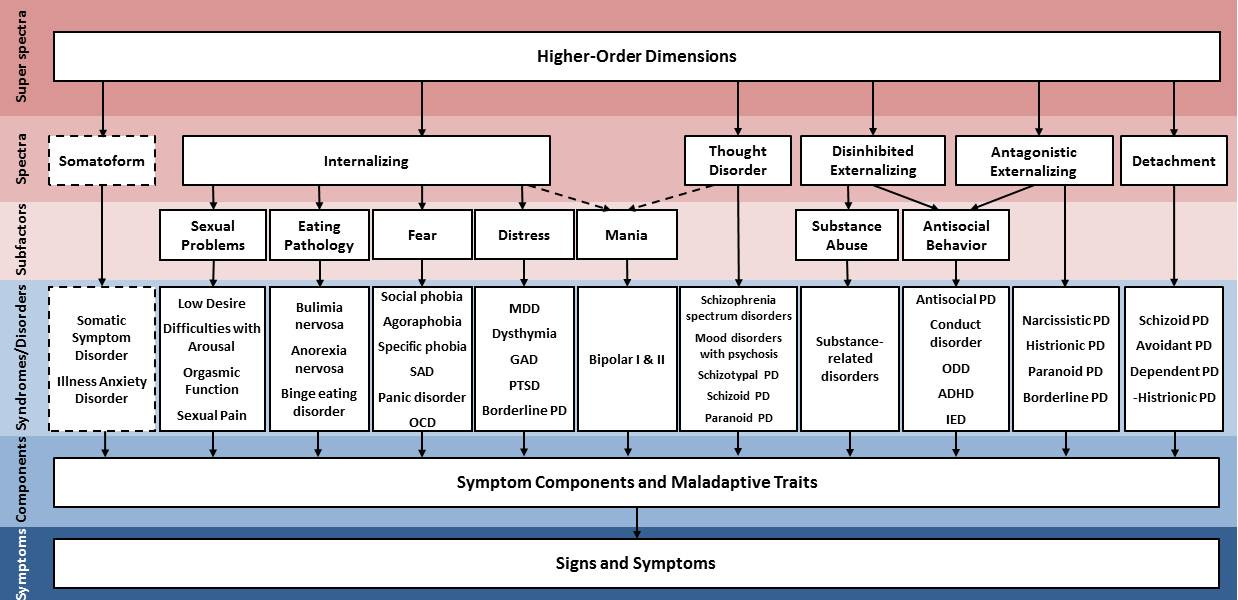

Of the two models, I’ve found the HiTOP to be the most compelling. At the core of the HiTOP are two well-established, ‘transdiagnostic’ (encompassing multiple diagnostic categories) dimensions of psychopathology: Internalising and Externalising. The Internalising dimension reflects a tendency to respond to emotional distress with inward-focused behaviours, such as emotion suppression and avoidance; Externalising refers to a tendency to ‘act out’ distress, e.g., aggressive behaviour, substance misuse. Internalising accounts for co-morbidity between traditional diagnoses such as mood, anxiety, and eating disorders, while Externalising accounts for substance use disorders (SUDs), antisocial behaviour, and similar issues.

But these two dimensions only account for a fraction of DSM-5 diagnoses. What of the others? The HiTOP proposes an additional 3-4 transdiagnostic dimensions, collectively referred to as ‘spectra’: Thought Disorder, which accounts for Schizophrenia spectrum and similar disorders; Detachment, which includes several personality disorders (most characterised by severe emotional or interpersonal detachment); and Somatoform, a currently provisional dimension that covers disorders with a significant somatic component (the physical manifestation of psychological distress). The Externalising dimension can be further divided into Disinhibited and Antagonistic spectra.

Don’t worry—I’m not expecting anyone to memorise this. The key thing to note about this model, aside from its focus on dimensions rather than strict categories, is its hierarchical nature. Like the FFM, the primary spectra can be further divided into sub-dimensions that include more specific symptom clusters, which themselves can be broken down into individual symptoms, and so on. Imagine the branches of a tree (such as that shown in the header of this post) and you’ll have a fair visual representation of what’s happening here. By thinking about psychopathology in this way, we can explore a person’s difficulties at the level of the root—the core of the presenting issue—or at the level of the twigs and leaves, the every day behaviours and symptoms that don’t fit neatly within a particular diagnostic box.

With all of that said, I want to emphasise that the map is not the territory here. No theoretical model can ever describe the phenomenon of psychopathology 100% accurately because, in reality, there’s more complexity beneath the surface than can be neatly summarised in this way. However, what the HiTOP offers is a more accurate representation of psychopathology that is consistent with the best statistical methods currently available. It also addresses many of the criticisms above. The problem of high co-morbidity is accounted for, as the common underlying factor between symptom clusters is now clearly identifiable; there are no binary categories (depressed vs not depressed), leading to less stigma and a reduced reliance on arbitrary cut-points; and instead of pathologising culturally-incongruent behaviour, we can shift our focus to subjective distress or impairment, and use this more generalised map of human psychology to identify the sources of these.

What Does This Mean for Clinicians and Clients?

Ultimately, mental health clinicians want to find the best methods possible to assess and treat psychological difficulties. Therapy can’t be successful without a solid understanding of the client’s problem(s), and the current approach used to assess and diagnose psychopathology simply isn’t up to scratch. A better system for conceptualising mental health issues will go a long way toward improving the effectiveness of treatment options, and I believe the HiTOP is a big step in the right direction.

Recall my original definition of psychopathology: a breakdown in ordinary psychological functioning which causes marked distress or impairment. In part 1 of this series, I introduced a number of important theories that together explain much of ordinary human psychology. What the HiTOP gives us is a model to understand what it looks like when these systems go wrong—and given my definition above, it won’t surprise you to discovered that the HiTOP actually has a lot in common with the FFM and cybernetic theory. In part 3, we’re going to bridge these seemingly disparate theories and, in time, revolutionise the mental health industry. Subscribe below to be a part of it.

(This is part 2 of a 3 part series On Personality and Psychopathology. I wrote an addendum to this post here. The third and final part of this series can be viewed here.)

Actually, this is a lie. A revision to the DSM-5 has recently been released. Rest assured, everything in this essay applies to DSM-5-TR as well.

Have you seen Slime Mold Time Mold's "The Mind in the Wheel" or Powers' Perceptual Control Theory?

Justifying calling two entirely different symptom presentations as BPD may be possible by asserting that these presentations share a common etiology or may benefit from being treated the same way. But the DSM isn't generally concerned with etiology, or treatment for that matter...