Cybernetics: The Key to a Unifying Framework for Psychology

First steps toward a unified psychological science. On Personality and Psychopathology, part 3

Psychology is sometimes criticised for lacking a unifying framework. To understand what I mean by this, think of evolutionary theory and its central role in the field of biology. Evolution provides a set of principles by which seemingly unrelated observations can be understood, and allows for more reliable hypotheses to be generated. Psychology doesn’t have this. Instead, what we have is a multitude of sub-disciplines that all have their own ideas about how humans act and why. Clinical psychology, which focuses on psychological dysfunction, is arguably the worst offender.

My goal in writing this series has been to lay the foundations of a solution to this problem. The theories and models I’ve covered so far are the building blocks of this solution, and in this final essay, I’m going to piece these together in a way that makes sense. For new readers, I’ve included a condensed recap of what we’ve covered to date. If you’re already caught up, feel free to skip ahead to Bridging Personality and Psychopathology below.

The Story So Far

Part 1: Understanding Human Personality

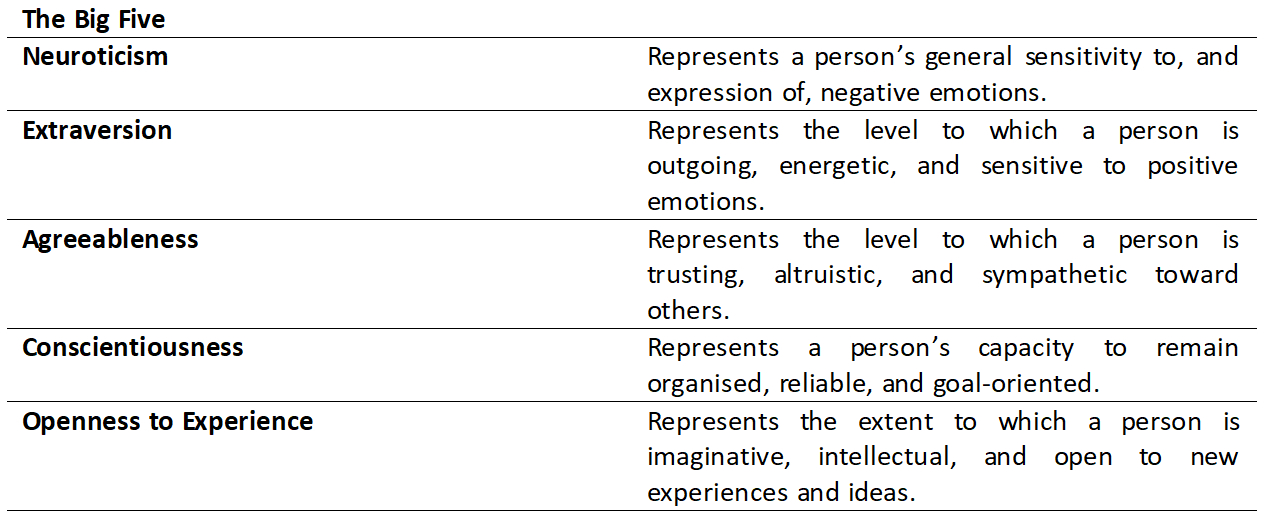

In part 1 (recently revised) I introduced the ‘Big Five’/Five Factor Model (FFM), a well-established model which describes human personality in terms of five key traits or dimensions: Neuroticism, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Openness to Experience. Each trait represents a relatively stable cluster of related cognitive, emotional, behavioural, and motivational tendencies, summarised below:

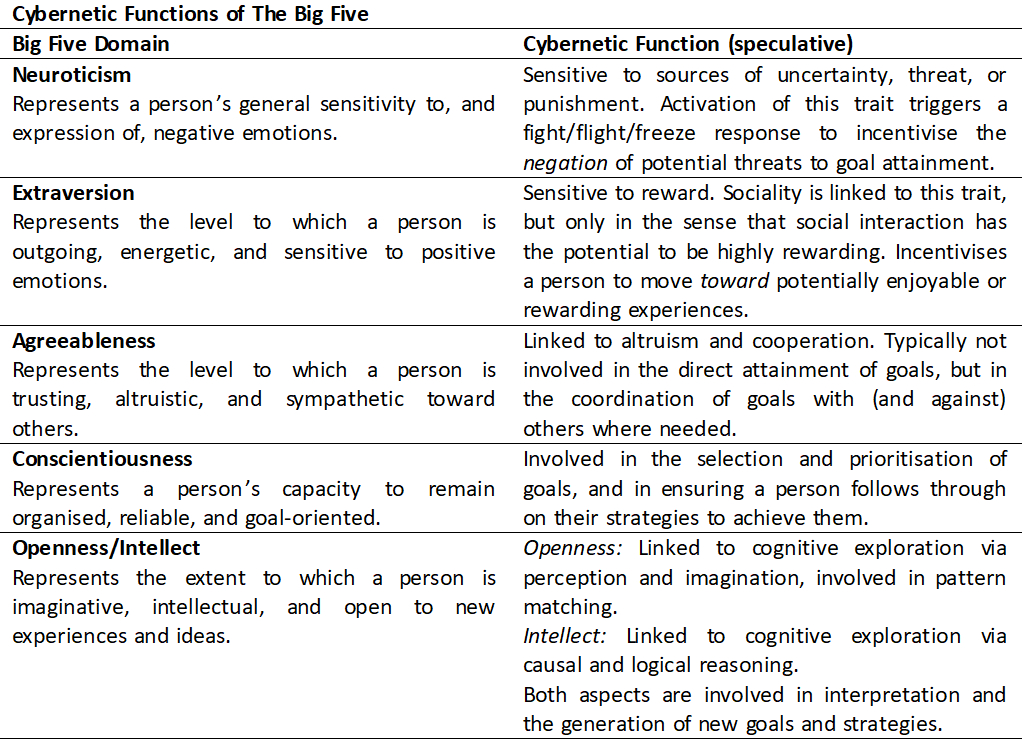

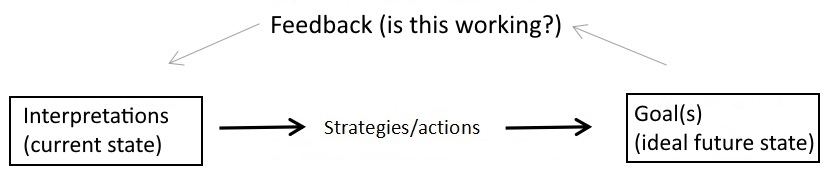

I also introduced DeYoung’s Cybernetic Big Five Theory (CB5T), which attempts to explain personality. CB5T is organised around cybernetic systems, “goal-directed systems that self-regulate via feedback”1. Big Five traits represent the stable parameters of these cybernetic systems, which trigger in response to broad classes of stimuli (think ‘danger’ or ‘socialising’) and generate active or inhibitory impulses to support the pursuit of core human needs (e.g., safety, social connection). When activated, these traits are expressed in a context-specific way (avoiding dark alleys, attending parties) called a Characteristic Adaptation (CA), a personalised, socio-culturally relevant expression of a Big Five trait that functions cybernetically. CAs involve a goal, strategies to achieve this goal, and an ongoing process of feedback and interpretation of information to assess whether progress is being made.

Although we might imagine the activation of a Big Five trait causing the expression of a single CA process, in reality, many of these processes are happening at once, and it’s not uncommon for the motivations driving them to conflict with one another (more on this later).

Finally, I briefly discussed the role of evolution in the development of these traits. In short, personality traits represent motivations and behaviours that have proven effective over evolutionary time to meet important human needs which emerged in response to environmental pressures.

Part Two: What the DSM-5 Gets Wrong About Mental Illness

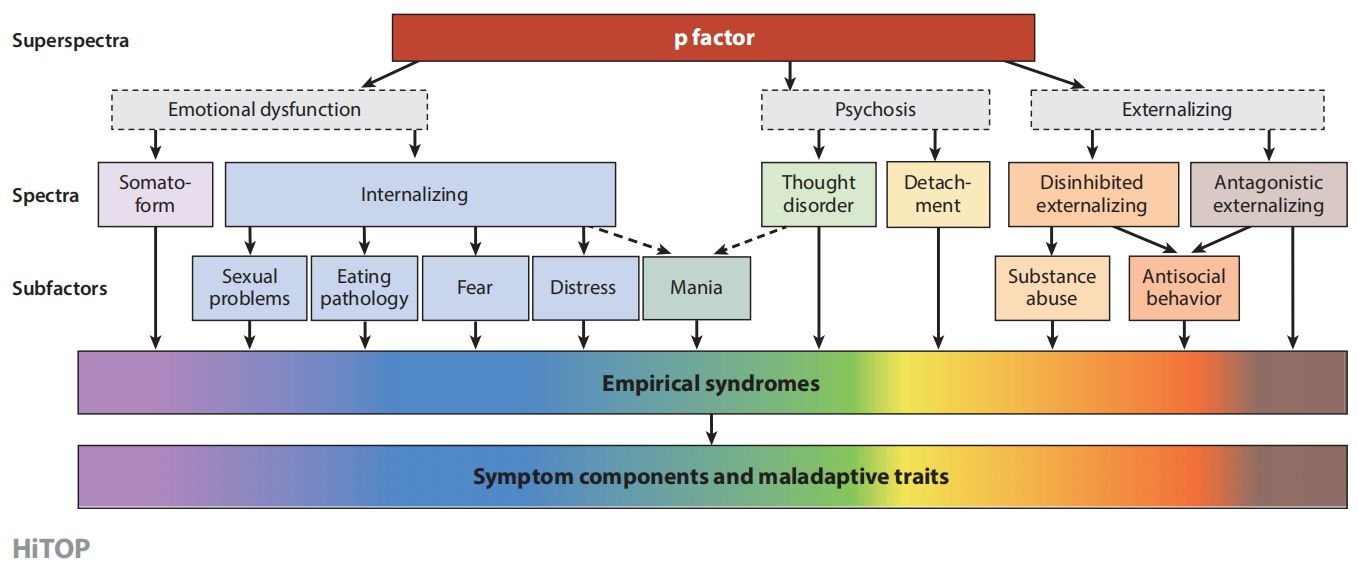

In part 2 (and its addendum) I discussed psychopathology, and introduced the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) as an alternative to the current DSM-5 diagnostic system. The HiTOP is the product of several decades of research looking at the co-occurrence of mental illness symptoms. In this sense, it’s similar to the FFM, which emerged out of research on the statistical co-occurrence of personality characteristics.

The HiTOP is organised around 5-6 core dimensions or spectra, which are situated in a hierarchical model of more specific and more generalised dimensions. Each spectra or sub-factor represents a cluster of related symptoms. For example, all eating problems are similar (showing similar behaviour patterns and cognitive distortions), so fit together within the Eating Pathology dimension. Eating Pathology symptoms and Fear symptoms have more in common than they do with Antisocial Behaviour symptoms, so fit together within the Internalising dimension.

No model or theory can ever fully capture reality, but the HiTOP offers a perspective on psychopathology (and human psychology in general) that is more consistent with contemporary research than previous taxonomies. It’s largely atheoretical, meaning it doesn’t assume the correctness of any prior theoretical model (such as psychoanalytic or cognitive theory); however, what has emerged is the realisation that psychopathology is best understood in terms of dimensions upon which we all sit, not categories into which we do or do not fit.

Keen-eyes readers will noticed that the HiTOP and FFM share many similarities. This is no accident! Now that we’ve covered the basics, let’s explore how these various ideas fit together, and what this means for our understanding of psychology and psychopathology.

Bridging Personality and Psychopathology

I previously defined psychopathology as a breakdown in ordinary psychological functioning that causes marked distress or impairment. What this means is that acquiring a mental illness isn’t like catching a virus. We can suffer psychological decline in response to life circumstances, but the change is ultimately internal, a kind of malfunction in previously functional cognitive and biological processes. The DSM-5 doesn’t deny this, but for the most part it isn’t organised in a manner that recognises this continuity between psychological function and dysfunction. At least, not in section II, the section that presents the main diagnostic criteria.

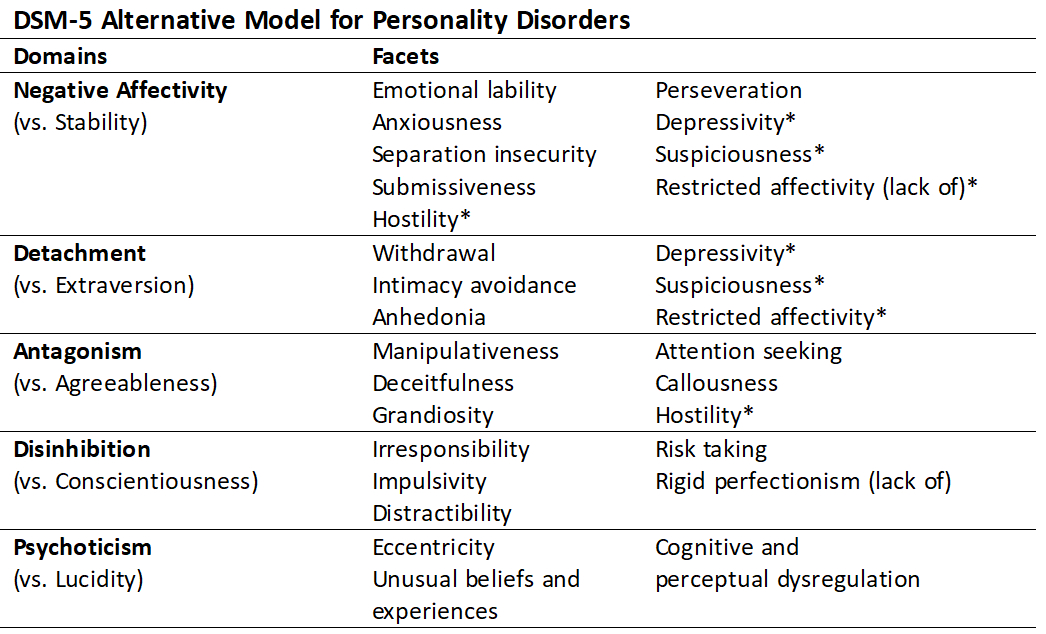

Section III of the DSM-5 tells a different story. Here, nestled alongside a number of ‘Emerging Models and Measures’, is an Alternative Model for Personality Disorders. Instead of describing personality dysfunction in terms of diagnostic categories, this Alternative Model posits five primary domains of dysfunction which cover a further 25 sub-dimensions:

By now you’ve no doubt noticed the pattern. The Alternative Model, like the HiTOP, converges on five core dimensions that seem to correspond with the Big Five. The DSM-5 section on the Alternative Model does go a little further, providing guidelines on how to diagnose personality disorders using this model, but the five domains of the Alternative Model are essentially extreme expressions of the Big Five. Negative Affectivity corresponds with FFM Neuroticism, Detachment with Extraversion, Antagonism with Agreeableness, and Disinhibition with Conscientiousness. In other words, whether we’re looking at ordinary personality traits, personality disorders, or other forms of psychological dysfunction, we seem to always be measuring the same thing.

There is one interesting exception. So far, personality researchers have been unable to establish a clear link between the Alternative Model’s Psychoticism domain and FFM Openness to Experience. Several researchers have suggested that, to properly understand this relationship, we instead need to look at this trait’s sub-dimensions. Openness to Experience can be sub-divided into two distinct dimensions (or ‘aspects’): Openness, which involves cognitive exploration of perceptual and sensory stimuli, and is associated with the experience of apophenia (inaccurate pattern matching, as in psychotic delusions); and Intellect, which involves exploration of abstract and semantic information, and is linked to intelligence/IQ. Psychoticism seems to be best predicted by a combination of higher Openness but lower Intellect; in others words, it is the combination of over-active pattern-matching and a reduced capacity for reasoned interpretation of this information that seems to cause psychosis and similar symptoms.

Again, no model can fully capture the complexity of human behaviour, and these ideas are not without their critics. But our understanding has come a long way, and the important takeaway here is that these different models of normal and abnormal human functioning seem to be measuring the same few things. This suggests that what we think of as psychopathology is ultimately a breakdown in the processes underlying ordinary human personality characteristics.

The Cybernetic Theory of Psychopathology (CTP)

When I first started researching these topics, I encountered the now well-established finding that psychopathology is associated with extreme scores on several of the Big Five traits. For example, many studies identify high Neuroticism, low Extraversion, and low Conscientiousness as predictors of Internalising disorders. Early on, I assumed that higher Neuroticism or lower Extraversion caused psychopathology. But this explanation proved inadequate—we’ve all met people who are incredibly introverted or disagreeable, and though some people may struggle as a result, others live perfectly happy lives this way. So what’s happening here?

In 2018, using CB5T as their foundation, DeYoung and Krueger published an article outlining the principles of a Cybernetic Theory of Psychopathology (CTP). CTP defines psychopathology as “persistent failure to move toward one’s psychological goals due to failure to generate effective goals, interpretations, or strategies when existing ones prove unsuccessful”2. Stated differently, psychopathology is a failure of the cybernetic processes underlying Characteristic Adaptations (CAs), the socioculturally-influenced, context-specific expressions of human personality traits.

Psychological Goals

CTP emphasises that psychopathology is a failure to achieve psychological goals. The human body relies on countless cybernetic processes to survive, including many that don’t require any psychological input, such as those involved in temperature regulation. For DeYoung and Krueger, the only goals relevant to psychopathology are those that involve the (conscious or unconscious) mental representation of a desired state, and can be voluntarily acted upon. This doesn’t discount that extreme conditions, hunger, or tiredness can impact a person’s mental well-being, but it recognises that it is our interpretation of these experiences that contributes to the development of psychopathology, not the experience itself. This is by now a pretty well established psychological principle. It’s the basis of many popular psychotherapy modalities (e.g., cognitive behaviour therapy), and also has roots in many ancient philosophical and spiritual traditions, such as Stoicism and Buddhism.

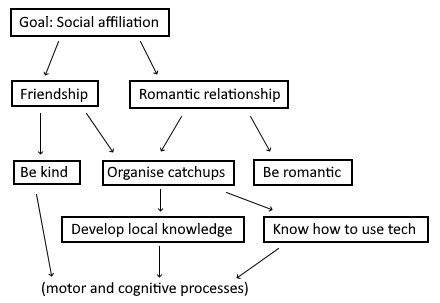

Psychological goals are organised hierarchically. To explain this, the authors give the example of social affiliation, the desire to interact and cultivate meaningful connections with others.

Social affiliation is quite a broad goal, so it requires gradual attainment of a series of sub-goals. A person may wish to cultivate both platonic and romantic relationships; to maintain these, they need to develop certain qualities such as kindness and romance, as well as more practical habits like organising dates. To organise dates, they need to have sufficient knowledge of local restaurants, know how to use a phone to book a table… and so on, all the way down to the level of motor and cognitive processes. Linking this back to cybernetics, a person with the goal of social affiliation will interpret their current social situation as undesirable, their desired future state as one in which they have fulfilling social and romantic relationships, and to achieve their goal, will engage in actions that push them further toward this goal. If this shows promise, they’ll continue along this path; if they receive feedback that’s discouraging (e.g., being rejected or ‘left on read’ too often), they’ll be forced to review this process and make changes.

The Uncertainty Problem: Psychological Entropy

What happens when someone is repeatedly unable to reach their psychological goals? In CTP, this is the key to psychopathology. Cybernetic dysfunction (and thus psychological dysfunction) is caused by an increase in unpredictability or uncertainty over the possibility of achieving one’s goals. This is referred to as psychological entropy. As entropy increases, a person can become too fearful or uncertain to continue (fear, anxiety), overcompensate in a desperate attempt to succeed (anger, obsession), or lose hope entirely in the possibility of moving forward (depression).

Psychological entropy increases for a number of reasons. One reason is that goals sometimes clash with one another. As this tension grows, a person becomes less able to compromise or prioritise their goals, and eventually becomes stuck. Entropy can also grow if the current state seems to difficult to escape (perhaps due to flawed interpretations), if one is unable to generate effective new strategies, or if a goal proves too difficult too achieve (leading to too many failed attempts). Even without these problems, entropy is always increasing. The world is in a constant state of change, so while our current goals, strategies, and interpretations may be adequate, this is unlikely to continue indefinitely into the future.

Personality Traits and Cybernetic Dysfunction

Each Big Five trait is believed to play an important role in the cybernetic process:

We can now start to understand the role of extreme personality traits in the development of psychopathology. Although unusual personality characteristics alone are not enough to cause mental illness, they can cause problems which increase entropy, and eventually result in cybernetic dysfunction (psychopathology). For example, a person high in Conscientiousness is usually able to achieve their practical goals, but if this causes a person to neglect other important goals (e.g., family obligations, personal well-being), they might eventually develop depression. In other words, extreme personality traits cause mental illness through their impact on the cybernetic system.

Wrapping Up

This series has been pretty information-dense, so let’s recap. Human personality is best described by the Big Five/Five Factor Model (FFM). Models that have emerged out of clinical research, such as the HiTOP and Alternative Model for Personality Disorders, seem to converge on the same five dimensions as the FFM. This suggests that mental illness isn’t like a foreign pathogen entering the body, but is in fact linked to internal personality processes. Cybernetic Big Five Theory (CB5T) posits that that these processes follow cybernetic principles, whereby personality traits act as the stable parameters (which predetermine the extent to which a person is motivated to avoid danger, approach opportunity, etc.) upon which a person’s context-specific goals, strategies, and interpretations (collectively, Characteristic Adaptations [CAs]) work to achieve important psychological goals. The Cybernetic Theory of Psychopathology (CTP) links this directly with the experience of mental illness, suggesting that psychopathology is essentially a failure to achieve one’s psychological goals due to a breakdown in these cybernetic processes.

That’s it! 7000-ish words summed up in a single paragraph. So what’s the point of all of this? In the introduction to this post I mentioned that psychology lacks a unifying framework. The concepts we’ve discussed in this series provide a coherent foundation upon which to start building this framework, especially with respect to clinical psychology. It’s my belief that most psychotherapeutic approaches are reinterpretations of the same few ideas. I want to use this framework to start comparing and contrasting these different models, to see if we can identify the necessary elements of good therapy (and perhaps the ‘good life’).

This brings us, finally, to my interest in stories. I believe stories are the way we organise our knowledge of ourselves, others, and the world. They are the missing piece—under the surface we have countless cybernetic processes motivating our actions, but we don’t consciously think in this way. It’s too cold, mechanistic, and inflexible. Stories are different. They can transmit a great deal of explicit and implicit information while remaining emotionally-engaging, and thus incredibly motivating. In my upcoming series, The Stories We Tell, I want to expand on this idea. We’ll explore everything from the internal tales we tell ourselves through to the grand narratives that comprise our mythologies, religions, and cultural traditions.

This is going to get very interesting. See you soon.

(This is the final part of a 3 part series On Personality and Psychopathology. Click here to view part 1 and part 2. I also wrote a follow up to this post integrating CTP with Cognitive Behaviour Therapy here.)

DeYoung & Krueger, 2018, p. 117.

DeYoung & Krueger, 2018, p. 121.

Great article - my interest was piqued at its conclusion, in particular. I wrote my dissertation on the importance of stories for human development, understanding, and mental health - on both an individual and broad societal scale. As a result - I wrote a novel as methodology. You can find its sequel https://karijanz.substack.com/p/episodes (if at all interested). The dissertation novel is in publication so it has not been posted but the series as a whole integrates/weaves features and symptoms outlined in the DSM-V into the lives of story characters. It focuses on existential and narrative therapies/theories as well as classic mythology as praxis. Excerpts from my study:

“Myths are healthy, necessary, and growth facilitating while providing structure for the development of meaning in one’s life (Hoffman et al., 2009). Stories are a way of being that evolved to reflect the structure of reality and all its patterned manifestations. A Darwinian-like feature of humanity, mythological interpretations of the world transcend history and have proven to be the most effective path to survival. There are standard occurrences in daily life that are portrayed and acted out universally. It turns out that the stories we tell have exactly the same structure, or core elements, that we see in Western mythology and the classic archetypes (Brunel, 2015). These have been developed as a way to deal with a world that is complex beyond comprehension, and one that often shifts in unpredictable ways.”

“We learn, grow, and understand our own stories through the stories of others, something Carl Jung (2014) believed to constitute a collective unconscious, one that is shared by all. Stories and mythology in Western culture evolved to have a common structure that is made up of the classic archetypes.”

“We all live in a story whether we realize it or not, and it is up to each of us to write it, otherwise we end up with a bit-part, living out the malevolent tragedy of someone else. When our personal story has been denied or rejected, mental health challenges emerge. Healing, then, requires the reintegration of story and self.”

Looking forward to your new series!

Big fan of the theory and the paper, insofar as one can be for academic stuff.

I feel like you got the descriptions turned around here(?):

Openness, which involves cognitive exploration of abstract and semantic information, and is associated with the experience of apophenia (inaccurate pattern matching, as in psychotic delusions); and Intellect, which involves exploration of perceptual and sensory stimuli, and is linked to intelligence/IQ.