Cognitive Behaviour Therapy: A Cybernetic Perspective

Bridging cybernetic theory and clinical practice.

The worth of a theory can be measured by its usefulness. I recently concluded my series On Personality and Psychopathology, which introduced several theories that together provide a coherent framework for understanding human psychology and psychopathology. A brief summary:

“Human personality is best described by the Big Five/Five Factor Model (FFM). Models that have emerged out of clinical research, such as the HiTOP and Alternative Model for Personality Disorders, seem to converge on the same five dimensions as the FFM. This suggests that mental illness isn’t like a foreign pathogen entering the body, but is in fact linked to internal personality processes. Cybernetic Big Five Theory (CB5T) posits that that these processes follow cybernetic principles, whereby personality traits act as the stable parameters (which predetermine the extent to which a person is motivated to avoid danger, approach opportunity, etc.) upon which a person’s context-specific goals, strategies, and interpretations (collectively, Characteristic Adaptations [CAs]) work to achieve important psychological goals. The Cybernetic Theory of Psychopathology (CTP) links this directly with the experience of mental illness, suggesting that psychopathology is essentially a failure to achieve one’s psychological goals due to a breakdown in these cybernetic processes.” - Cybernetics: The Key to a Unifying Framework for Psychology

How does this translate into treating psychopathology? In this post I want to explore this question through the lens of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT)1, a treatment approach I use in my own practice. CBT is a well-established therapy that’s been shown to treat a wide variety of mental disorders. It’s not a ‘cybernetic therapy’, but if cybernetic personality processes are at the core of psychopathology, then we should be able to identify principles of the Cybernetic Theory of Psychopathology (CTP) in effective therapies like CBT. I’ll begin by providing a basic overview of CBT itself, and then we can speculate on how cybernetics and CBT fit together.

The Basics of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy

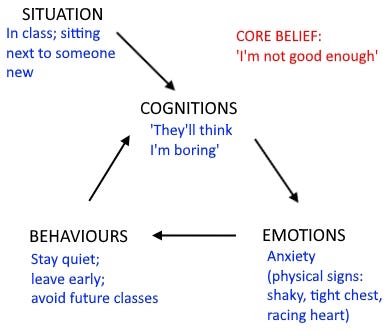

For this drive-by introduction to CBT, I’m going to focus on a disorder I often see in my work: Social Anxiety Disorder (Social Phobia). Social Phobia is characterised by “a marked fear or anxiety about one or more social situations in which the individual is exposed to possible scrutiny by others”2. The ‘core psychopathology’ is a fear of negative evaluation. From a CBT perspective, social situations trigger negative cognitions (thoughts) such as “I’ll embarrass myself” or “they’ll think I’m boring”, which ultimately reflect a distorted core belief about oneself or others (e.g., “I’m not good enough”, “people are judgemental”). Activation of these thoughts causes anxiety, which then leads to the use of unhelpful safety behaviours to cope. Safety behaviours provide short term relief, but cause long term problems; as a person becomes more reliant on these behaviours, they miss crucial opportunities to build social skills and learn that social interaction is generally harmless. This reinforces their fears and leads to more anxiety in the future.

In my own practice, I typically spend the first session getting to a know the client and assessing their presenting issues. I’ll then provide some psycho-education, and work with them to develop a formulation of their problem. Depending on the client, I might present a detailed formulation in terms of the ‘four Ps’ (Predisposing, Precipitating, Perpetuating, and Protective factors), but I’ll always do a more symptom-specific formulation of a person’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviours in triggering situations (similar to Figure 1), and the impact of these on their life.

In the first few sessions, it helps to teach an anxious client stress-reduction strategies they can use to regulate their anxiety. However, my main focus in these early sessions will usually be identifying and challenging negative automatic thoughts. For the anxious client, these tend to be very catastrophic or self-critical. The goal of this cognitive work is to reduce the person’s belief in the accuracy of these distorted beliefs and to help them to see that, even if their fears do eventuate, this won’t be so bad.

A purely intellectual understanding of this is rarely enough. To achieve therapeutic change, a person needs to actually experience the change on an emotional level. The behavioural side of CBT includes a variety of strategies that work to gradually re-expose a person to avoided triggers, reduce a person’s reliance on unhelpful short-term coping strategies, and reinforce more helpful behaviours. In doing this, the person gets to experience themselves coping effectively in difficult situations, which further reinforces a belief in their own competence and ability to cope. It’s easy enough to ignore evidence of one’s competence when it’s merely an intellectual exercise, but it’s much harder to ignore the evidence of first-hand experience.

Some clients do require additional skills development work on top of this (e.g., to build effective communication skills), but otherwise, this is CBT in a nutshell. More recent treatment manuals will include things like mindfulness meditation and values-based decision-making, and I include these in my own work too, but what I’ve outlined here are the fundamentals of CBT.

The Cybernetics of CBT

How do the principles of the Cybernetic Theory of Psychopathology apply to CBT? First, a quick primer on CTP. CTP emerged out of research on the cybernetics of personality. Big Five personality traits represent the stable parameters of a person’s Characteristic Adaptations (CAs)—their observable, context-specific goals, strategies, and interpretations that work to achieve key cybernetic/psychological3 goals. We have multiple psychological goals active at all times, and these goals are hierarchically structured, meaning they can be broken down into increasingly minute sub-goals (down to the level of individual motor and cognitive processes). Psychopathology is the result of increased uncertainty (‘psychological entropy’) regarding the possibility of achieving one’s psychological goals, typically after repeated failure to do so.

Take the example of 19-year-old Chad, referred by his GP for ‘depression and anxiety’. Chad is a university student in his second year of Economics. He thinks of himself as sociable and competent; he was popular in high school, captain of the football team, girls loved him, and he always managed to average Cs and Bs in ‘the subjects that mattered’. Since starting university, things have changed. He’s struggling to meet people (most of the other guys aren’t interested in sport), and without the structure and oversight of high school, he’s failing his classes. He feels anxious, unmotivated, and now spends most of his time playing video games alone.

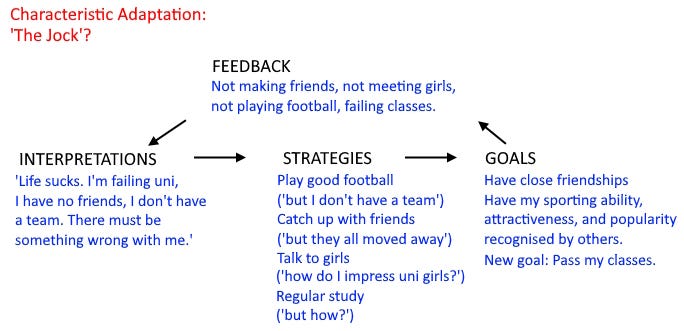

Chad essentially has the identity of a ‘Jock’ (although he probably wouldn’t call himself that). In CTP terms, the Jock identity is a CA.

Chad has pre-established goals of being popular and valued for his sporting ability. Academic success is important only insofar as it doesn’t conflict with these more important goals. He has developed effective strategies that, in a high school setting, work well for achieving these goals. He gets feedback in the form of athletic, social, and romantic success, and correctly interprets this to mean that he is achieving his goals.

So what changed? Chad has the same goals, but he now has another: to pass his classes. He’s getting feedback which indicates that, not only is he not achieving this goal, he’s not achieving any of his previous goals either. Psychological entropy (uncertainty) has increased to a point where his existing CA is no longer sufficient. The context has changed, and Chad’s strategies are no longer adequate. He’s beginning to interpret this to mean that he is inadequate, he is a failure, and that there’s no hope for future success. He is experiencing significant self-doubt (anxiety) and hopelessness (depression).

Assessment and Goal Setting

Most of this information would be identified in the first few sessions. Based on Chad’s symptoms, a psychologist or psychiatrist might go on to diagnose him with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and Social Phobia if additional criteria were met. A CTP-informed therapist wouldn’t necessarily give a diagnosis, but would want to assess Chad’s placement on the various dimensions of the HiTOP. This assessment would also include an assessment of Big Five personality traits, which (as regular readers will know) overlap significantly with the HiTOP dimensions. Most therapists don’t explicitly assess personality traits, so in regular CBT this part of the formulation would be largely speculative. Chad probably has Big Five scores of higher Extraversion, perhaps higher Agreeableness, and lower Conscientiousness; given the recent emergence of anxiety and depression symptoms, he may also be higher on Neuroticism.

As part of the initial assessment, Chad and his therapist would identify treatment goals. These may or may not correspond with Chad’s cybernetic/psychological goals, but a thorough CBT-based assessment of Chad’s situation should do a reasonable job of matching these up. Chad’s stated goals are to ‘feel happy again’ and ‘make new friends’; the therapist would help him to specify what achieving these goals would actually look like (in other words, what feedback they should be looking for; e.g., he’d be skipping fewer classes and making new friends), and also identify whether the problem is related to faulty interpretations or feedback processes, or due to a lack of skills. In the latter case, a full 10+ sessions of CBT may not be needed. Instead, therapy would focus more on building communication skills or good study habits. In Chad’s case, it’s probably a combination of both.

Challenging Faulty Interpretations

The ultimate goal of CBT is to challenge and modify negative automatic thinking patterns that maintain a person’s emotional symptoms. As someone with Social Phobia, Chad believes that he is socially defective in some way (e.g., boring, awkward). He might catastrophise over perceived interpersonal failures, causing significant rumination or anticipatory anxiety, or he might fixate on his own mistakes and physical symptoms of anxiety in social situations. In any case, he’s like to ignore or dismiss any evidence to the contrary. These are all problems of interpretation, and CBT is arguably most effective in addressing these kinds of problems. Chad’s therapist could engage him in a cognitive restructuring exercise, in which he would (for example) compare the evidence for and against the idea that he’s ‘socially awkward’. This would provide an opportunity to view the situation from a more neutral perspective, and with consistent practice, would reduce his automatic tendency to think of himself as ‘awkward’.

Negative interpretations can also be challenged behaviourally. Chad’s therapist could guide him through behavioural experiments to directly test out his fears (e.g., by acting intentionally awkward in social settings and reflecting on the outcome), or through a process of graded exposure, whereby he would ‘face his fear’ in a series of increasingly anxiety-provoking situations to gradually build his tolerance. Over time, Chad would come to interpret these situations as harmless, lessening his anxiety.

What about Chad’s depression? Cognitive strategies can help with this too. However, in CBT there’s a behavioural intervention—Behavioural Activation (BA)—that is particularly useful for depressed clients. Where anxiety tends to be a problem of excessive worry, depression is characterised by pervasive hopelessness. In cybernetic terms, the person is either so overwhelmed by external feedback (or their interpretations of this feedback) that they can’t envision new ways forward, or they believe so strongly that their strategies will fail (“I’m not good enough”) that they view any attempt to act as fruitless. For Chad, BA would involve scheduling activities that generate a sense of enjoyment or achievement (such as seeing old friends or joining a football team) to reignite hope that he can enjoy life again, and that he can achieve things and prove himself a capable person.

Final Comments

This is a rough first attempt to integrate CTP with an existing psychotherapeutic modality. I’ve skipped over the feedback portion somewhat—this post is already long enough—but as I see it, contingency management and mindfulness techniques are best positioned to target this part. I’ll return to this another time.

The big takeaway here is that the mechanisms of CBT can be effectively understood in cybernetic terms. This suggests that the psychological processes targeted by CBT might themselves be organised in a cybernetic manner. If we want to develop more effective treatment methods, I believe we need to incorporate cybernetic principles more explicitly; CTP provides an excellent model upon which to start building new formulations and interventions.

This said, I maintain that cybernetics alone is insufficient for understanding human psychology or psychopathology. Take Chad above—his identity as a ‘Jock’ wasn’t fully formed at birth. There’s a whole history and context in which this developed (his ‘backstory’), and when Chad attempts to understand or express who he is, these are the details he shares. This is the narrative portion, the story to which I alluded in my previous post. It’s the cognitive framework through which all of these cybernetic processes make sense to ourselves and others.

I plan to explore this idea further in my upcoming series The Stories We Tell. Stay tuned.

There are countless popular and clinical manuals on CBT. David Tolin’s Doing CBT is a great introduction for clinicians.

DSM-5, p. 202.

In CTP, these are the same thing.

I like the cybernetics concept as a model here, but the use of the term psychological entropy is confusing. Is this equivalent to an error signal we would typically talk about with cybernetics?