Understanding Human Personality

Exploring the whats, hows, and whys of human personality. On Personality and Psychopathology, part 1

A person’s personality, in everyday language, is who they are—what makes them unique and distinct from other people. We speak of people having particular traits, but also of being of a certain type; when a person is acting strangely, we say they’re not themselves, and after not seeing someone for many years, we might notice that they’re no longer the same person. All of this suggests that personality not only refers to who a person is, but who they are not, and that a person’s personality may change in certain situations or across time. To go a little further, many would agree that different groups of people can have personalities, reflected in terms like feminine, masculine, and national character.

Personality psychologists have gone back and forth on the question of whether personality can change. While most researchers view personality as largely stable, there are many exceptions—for example, the way personality is expressed can vary somewhat moment-to-moment (without lasting change to the underlying measured trait), and lasting changes do seem to occur over large spans of time or in response to major life events, like having a child. Where many researchers deviate from common wisdom is in their rejection of the concept of personality types, which have not been reliably identified statistically, and inherent group differences (more controversial; the statistical evidence is mixed, but for various reasons psychologists are generally hesitant to accept evidence of characteristic group differences not explained by social or environmental factors).

On the whole, I think it’s fair to say that personality researchers have largely confirmed what people already knew. Where they differ, it seems to be a matter of differing definitions and standards for evidence. For example, certain personality traits do co-occur more than others—it’s probably not just chance that there is a recognisable type of person who is, for example, more outgoing and more personable—but whether these trait clusters are distinct enough to be formally understood as personality types is a matter of interpretation. Researchers have also developed some useful models and theories to help us understand personality. The Five Factor Model (FFM) is one; DeYoung’s Cybernetic Big Five Theory (CB5T) is another, and one that I’ve found particularly useful when exploring these topics. These are important ideas, and ones I’ll return to in future posts, so let’s dig into them.

The ‘What’ of Personality: The Five Factor Model (FFM)

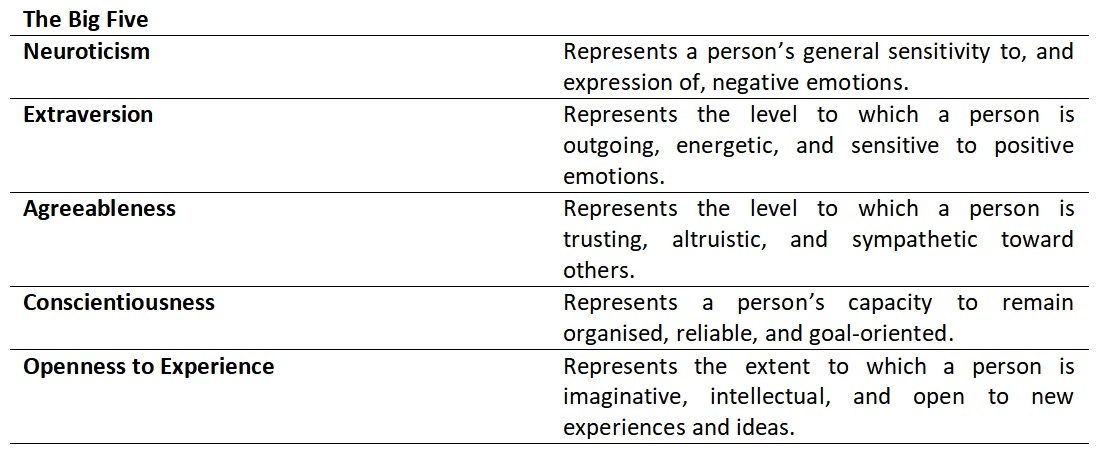

The FFM is a set of five key traits which represent relatively stable clusters of cognitions, emotions, behaviours, and motivations. These traits were first identified by researchers interested in the analysis of language, who noticed that adjectives used to describe human behaviour tended to cluster into groups of related words (e.g., ‘extroverted’, ‘outgoing’, and ‘social’). These groups were later confirmed through more advanced statistical methods, and most personality researchers now agree that personality is best described by the ‘Big Five’: Neuroticism, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Openness to Experience. The Big Five are best thought of as dimensions, or sliding scales, that represent how we are likely to act most of the time. For example, someone high on the Agreeableness dimension would tend to be more polite in conversation, and more likely to act in ways that account for the needs of others. There may still be circumstances under which this person would act in a disagreeable or hostile way, but these situations would be few and far between.

The FFM is useful because it allows us to measure the influence of personality on our lives. Personality differences are known to predict future physical and mental health, relationship quality, job choice and performance, values and political ideology, and much more. Personality has also been shown to differ between various demographic groups, which has huge implications for social and political dynamics. For example, certain gender stereotypes seem to hold true: men tend to be less agreeable and nurturing, but more emotionally stable than women; men prefer to work with ‘things’, whereas women prefer to work with people. On the other hand, cross-cultural differences have been found that often contradict common stereotypes. African nations tend to score higher on Conscientiousness, Agreeableness, and emotional stability (reversed Neuroticism), while East Asian nations tend to score lower on Agreeableness and Conscientiousness, among other differences. Some reasons for these differences are provided in the linked article, but this is a big (and controversial) topic, so I’ll discuss this more in a future post.

Are the Big Five a product of ‘nature’ or ‘nurture’? As with most human traits, there’s a strong genetic component, with researchers estimating that personality is around 50% heritable. We certainly don’t enter the world as ‘blank slates’. Beyond this, though, things get tricky; our genes predispose us to looking, acting, and perceiving in particular ways, and as we interact with our (very social) environments, we invite different responses which may reinforce or punish particular gene-driven behaviours. Furthermore, we’re subject to additional social/environmental pressures that are entirely unrelated to us as individuals, yet influence us in countless explicit and implicit ways. In short, when it comes to nature vs nurture, the truth is an almost impossible to quantify combination of the two.

The ‘How’ of Personality: Cybernetic Big Five Theory (CB5T)

Cybernetics and Personality

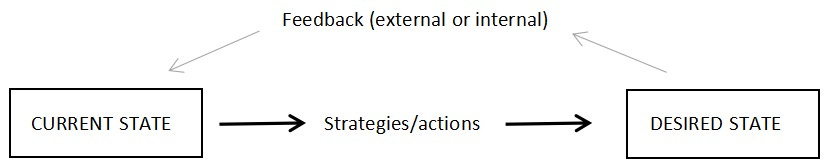

One of the more comprehensive of the various theories developed to explain how personality functions is DeYoung’s Cybernetic Big Five Theory (CB5T). In CB5T, ‘cybernetic’ is used to refer to “the study of principles governing goal-directed systems that self-regulate via feedback”. It’s used in a manner not dissimilar to the word ‘homeostatic’, e.g., as in the regulation of temperature, hunger, and wakefulness. In short, humans are made up of many cybernetic systems; in each of these systems, we maintain a concept of our current state, a desired future state, and what we need to do to get there. We then keep ourselves to task based on positive or negative feedback. The basic cybernetic process looks like this:

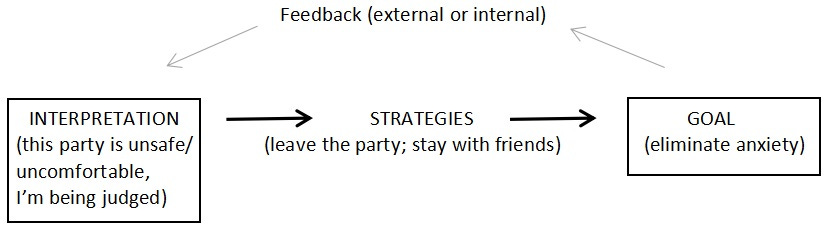

And in practice, looks something like this:

For DeYoung, personality traits (as measured by the FFM) represent key parameters in these cybernetic systems. Our position on a particular Big Five dimension represents the strength and direction of our motivation toward a particular goal or state of being (e.g., social, free from danger) and predisposes us to think, feel, and act in certain ways to achieve these goals. The FFM trait Neuroticism, for example, is characterised by sensitivity to negative emotion, and reflects our cognitive and behavioural tendencies in response to threat, punishment, or uncertainty. Someone higher in Neuroticism will generally experience the ‘fight-flight-freeze’ impulse sooner or more intensely, and will be quicker to act on this impulse.

Characteristic Adaptations (CAs)

Characteristic adaptations (CAs) are a person’s behaviours, emotions, thought processes, and motivations that we actually see in the world. CAs are socioculturally dependent; where an underlying personality trait (e.g., Neuroticism) is activated in response to broad classes of stimuli (such as ‘threat’ or ‘uncertainty’), the CA is the expression of that trait in response to the specific circumstances under which it was activated (e.g., running away or fighting back against a mugger). Whereas FFM traits are universal, CAs differ across cultures and situations. This explains individual differences in the expression of a trait even where two people score the same on a measure of that trait.

DeYoung takes issue with the ‘laundry lists’ of CAs developed by previous personality theorists, and prefers to simplify these into three categories: interpretations, strategies, and goals. In this way, CAs map easily onto the basic cybernetic model. Goals are desired (socioculturally-dependent) future outcomes based on core human needs, interpretations are the ways in which a person interprets the world in relation to a particular goal, and strategies are the plans and actions taken to achieve that goal. The goal acts as a reference point by which the whole process is measured; if a goal continues to go unmet, a person must revise their interpretation of the current situation, modify their strategies to improve their chances of success, or decide on a new goal that is more achievable. Thus, the goal for a person higher on Neuroticism is safety or emotional security; the strategy is to escape, lash out, or freeze up in some socioculturally relevant way; and the interpretive frame is one in which there is a generally heightened threat of punishment, judgement, or similar.

TL;DR

This is a lot, so to summarise: CB5T asserts that human personality can be understood by reference to cybernetic systems, goal-directed processes that self-regulate via feedback. Personality traits—the Big Five—represent the level and direction of a person’s motivation toward core human needs (e.g., safety, social connection), as well as the behavioural/emotional/cognitive tendencies expressed in order to meet these needs. CAs are the specific behaviours, emotions, thought processes, and motivations we actually see in the world; CAs are understood as cybernetic systems, whereby a person will have socioculturally-influenced goals and interpretations, and contextually-dependent strategies which allow them to achieve these goals. In cybernetic terms, the Big Five are the basic parameters that determine when and how these CAs will be expressed. All of these processes are influenced by both genetic and environmental factors, and remain relatively (though not entirely) stable across a person’s lifespan.

The ‘Why’ of Personality: Evolutionary Theories

In many sciences, the ‘why’ question is typically answered by reference to Evolution. Why did finches develop differently shaped beaks? Why did giraffes develop such long necks? Why did humans develop such large brains? In all cases, it seems to have been evolutionarily advantageous to do so.1 Or, more accurately, the trait was a mutation that happened to be better suited to the organism’s environment at the time, the organism survived, and the trait stuck around.

When it comes to personality, many theorists believe something similar. There are a finite number of core needs that all humans require (sustenance, safety/survival, etc.), and through trial and error over many thousands of years, we stumbled upon behavioural tendencies that helped us to meet these needs. Threat sensitivity, social connection, adherence to group norms, impulse control, innovative problem solving—all humans have the capacity for these things because they proved beneficial at some point in our ancestral past. Of course, few traits are exactly the same from organism to organism. Some giraffe necks are shorter, some are longer. Some human brains are smaller, some are larger. There is variation, an element of randomness that generates a spectrum of possible behavioural tendencies, and more adaptive variants of a trait will tend to get passed on. So it is with personality traits. Some people score higher on Neuroticism than others, which in certain historical environments likely kept them safer, leading to the proliferation of this trait. In the same way, lower Neuroticism provides other benefits to a person (to speculate a little: the ability to remain calm under stress, an aura of [sexy] confidence, and the ability to mask emotional distress), and so this too has remained in the human toolkit.

There’s a lot to say about evolution as it applies to human behaviour. Personality traits may indeed have developed through adaptation, but they may instead be ‘spandrels’, harmless by-products of other more adaptive features. I’ll return to these topics in a future post, but for now, I’ll leave you with a few questions: Why do we have these traits and not others? What happens when a trait stops being adaptive? What happens when a person’s core needs (or strategies to meet them) conflict? Are there other, non-evolutionary explanations for why we have personalities? Stay tuned!

(This is part 1 of a 3 part series on Personality and Psychopathology. See part 2 here)

Edit 18/02/23: I revised several sections of this post to better define traits and make the relationship between traits and CAs more clear. I also slightly altered the title.

Presumably - I haven’t actually fact-checked these.

This series is so illuminating - just reading through the whole thing now. I’d appreciate your thoughts on this comparison:

Would you say FFM is analogous to genotype and CB5T more like phenotype?