Essay Club: The Origins of Cognitive Thought by B. F. Skinner

"Extraordinary things have certainly been said about the mind... but what it is and what it does are still far from clear."

Welcome to the third instalment of Essay Club! Last time we discussed C. S. Lewis’ The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment, which prompted some insightful reflections on the nature and morality of punishment in contemporary society. Today we’ll be reading The Origins of Cognitive Thought by psychologist B. F. Skinner.

This one’s a little more technical than our previous essays. If you’re not someone who makes a habit of reading academic psychology papers, feel free to stick with the summary below. However, if you do have a genuine interest in psychological science, I recommend reading it yourself. It only takes about 20-25 minutes, and it’s quite interesting. I suspect you’ll leave with a newfound respect for Skinner’s philosophy.

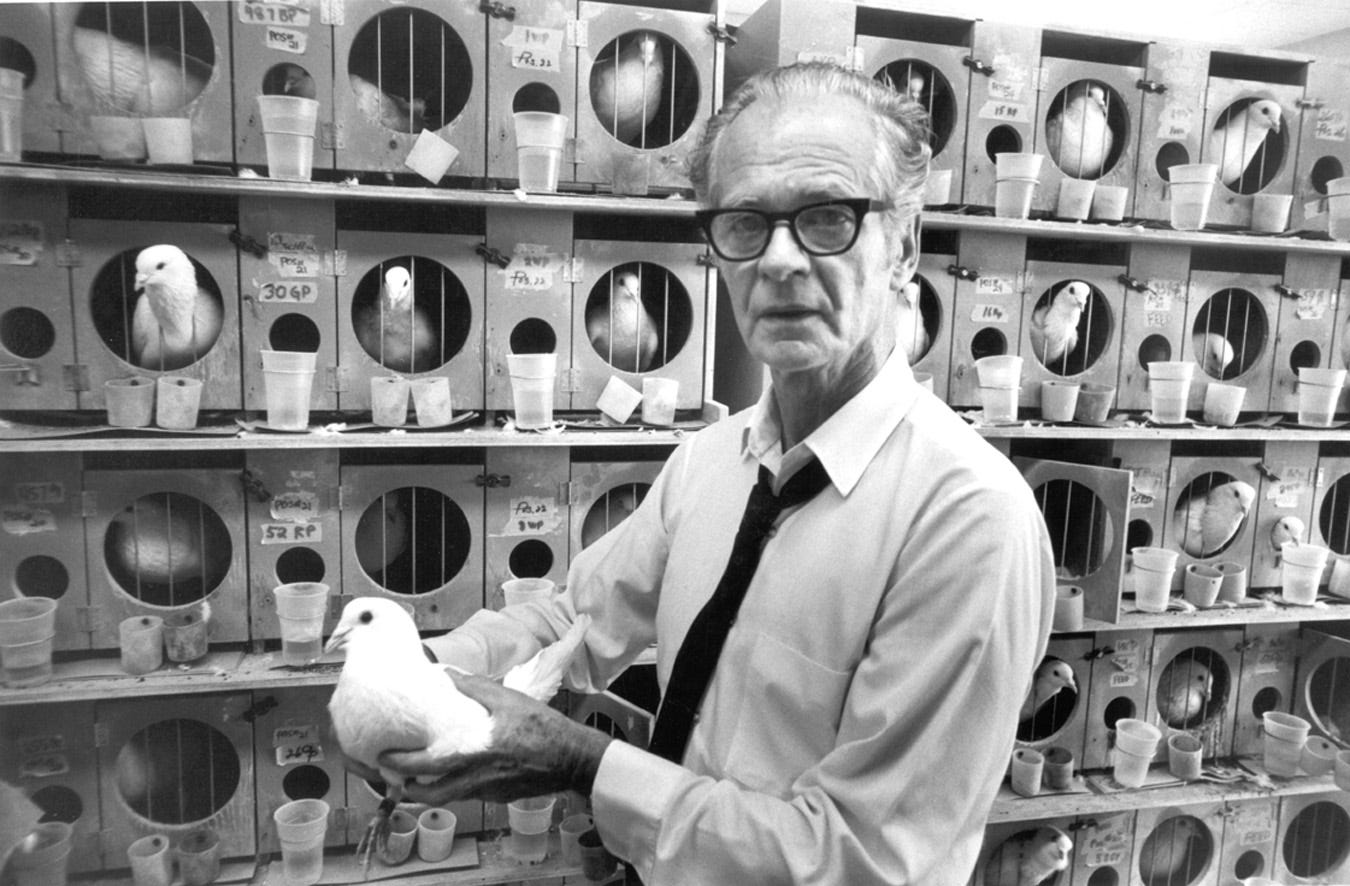

Burrhus Frederic Skinner (1904-1990) was an American psychologist, philosopher, writer, and inventor. He’s a fascinating figure—the more I read about him, the more interesting he becomes. As a writer, he primarily published academic works, but was also the author of a utopian fiction novel: Walden Two (published just a year before Orwell’s 1984). As an inventor, he developed a popular experimental tool called the ‘Skinner Box’, and also proposed a variety of other innovative inventions which included a high-tech baby crib and a pigeon-guided missile (I’m not joking).

Skinner was most well known for being one of the leading proponents of Behaviourism. As researchers, Behavioural psychologists rejected introspection and theoretical speculation on internal thoughts and feelings, preferring to study human behaviour through careful experimental manipulation, measurement, and observation. They argued that all behaviour is conditioned, meaning it emerges in response to external influences such as reward and punishment. Skinner’s stance was even more absolutist. Calling himself a Radical Behaviourist, he proposed that:

“behavioral events may be understood and analyzed in relation to past and present environment and evolutionary history without residue. That is, accounts of behavior with respect to environment and evolution leave nothing out: no internal states, intervening variables, or hypothetical constructs are required. Neurophysiology may be omitted too, not because it is hypothetical, but because it reveals only mechanism and not how present behavior came to be. No amount of understanding of mechanism can substitute for an understanding of [evolutionary and environmental1] history.” - What is Radical Behaviorism? A Review of Jay Moore's Conceptual Foundations of Radical Behaviorism

What this means is that even very cognitive ‘behaviours’ like language (which Skinner referred to as verbal behaviour) are a product of our conditioning. The basic idea is that language is merely a series of muscular movements to which we have given meaning, and learned to repeat. In infancy, we naturally experiment with our newly developing muscles, trying out new movements and sounds, and some of these sounds are reinforced by the people around us. We have no predisposition to saying or understanding the word ‘hello’, but a baby makes an ‘eh-oh’ sound, dad smiles and says ‘hello!’, and the baby learns that this series of muscle movements is significant and should be repeated.

Skinner’s ideas faced substantial criticism in his time, and they continue to be debated today. I mention all of this because to understand The Origins of Cognitive Thought, some background is needed. Skinner’s essay forms part of his ongoing defence of Radical Behaviourism, and while his ideas never fully took hold in psychology, they have been highly influential. Clearly, he was on to something—and in this essay, written toward the end of his life, I think we see a little bit of this ‘something’ shine through.

The Origins of Cognitive Thought (1989)

Skinner begins his essay with a proposition: “Etymology is the archaeology of thought”. He elaborates:

“What is felt when one has a feeling is a condition of one's body, and the word used to describe it almost always comes from the word for the cause of the condition felt. The evidence is to be found in the history of the language—in the etymology of the words that refer to feelings… To describe great pain, for example, we say agony. The word first meant struggling or wrestling, a familiar cause of great pain. When other things felt the same way, the same word was used.”

In other words, to understand the origins of any internal human condition—any feeling, any impulse—we need only study the history of the words used to describe them. In this essay, Skinner will argue that the same is true for the words used to describe our thoughts and mental processes. What follows is an exploration of the etymologies for many of the words used to describe various cognitive processes.

I won’t list every word examined in the essay, but it’s worth highlighting a few notable examples. When we experience a strong urge to do something, we say that we are inclined to do it, meaning we are leaning in the direction of doing it. When we understand something we comprehend it, from the Latin prehendere, meaning to seize or grasp. The words anguish, anxious, and worry all have origins in words that mean to choke; to be perplexed is to be entangled. When we remember, we are not simply recalling a stored image, but are [being] mindful of again, literally re-living our experience of the remembered thing (and all of the thoughts, feelings, and action tendencies associated with it).

On and on it goes—and what we begin to notice is that these words are all describing either the causes or consequences of human behaviour, or parts of the moment in which action occurs (immediately before, during, or after). In Skinner’s own words:

“No account of what is happening inside the human body, no matter how complete, will explain the origins of human behaviour. What happens inside the body is not a beginning. By looking at how a clock is built, we can explain why it keeps good time, but not why keeping time is important, or how the clock came to be built that way. We must ask the same questions about a person. Why do people do what they do, and why do the bodies that do it have the structures they have?”

The answer, according to Skinner, is that the origins of all human action, whether cognitive or behavioural (if such a distinction can be made), are to be found outside of the person, not within. Our sensations, perceptions, expectations, motivations, fears, desires, and the actions they generate don’t occur spontaneously. They are a product of our environment, conditioned into us over the course of our life.

Even those cognitive processes which we think of as ‘pure thought’ are merely a part of behaviour. Skinner lists a few examples: When “no effective stimulus is available” we discover or search for one, in order to have something to do; we collate our understanding of seemingly unrelated things by concentrating on them, which allows us to act more effectively; when we finally decide, we have determined the correct course of action. In short, “to think is to do something that makes other behaviour possible”.

So why is this important? In psychology, there is a lot of research and speculation on internal human experiences. Countless theories have been proposed to explain our thoughts and feelings, and a variety of different methods have been developed to measure these experiences in laboratory settings. But these methods are imprecise. If not administered carefully, their use can lead to sloppy research practices and flawed results. Skinner was a true scientist, and at its core, this is what Behaviourism represented—a focus on only those aspects of human experience which can be directly observed and measured, and the use of empirical methods and scientific language that lend themselves to this approach.

I agree that there is value in this, and feel that many psychologists would benefit from stripping their research back to these fundamentals (especially those who rely too heavily on survey data, which has many drawbacks). On the other hand, I disagree with Skinner’s apparent belief that all of human behaviour can be explained in this way. Radical Behaviourism represents a true ‘blank slate’ theory of human psychology, and this perspective has proven to be simply untrue. Human intelligence (measured by IQ) is a clear example. While it’s possible to maximise a person’s intellectual potential through good upbringing, nutrition, and education, no one has yet found a replicable behavioural strategy for increasing a person’s base level IQ. The implication of this is that there is a strong biological basis to human intelligence, and there is therefore a hard limit to what can be achieved through conditioning.

Questions and Essay Selection

Let’s discuss! As always, please share your own questions and thoughts in the comments. Here are a few questions to kick things off:

What do you make of Skinner’s core thesis? Can (or should) all human cognition be described in behavioural terms?

For those who read it, how did you find Skinner’s written style? Was this easier or harder for you than the essays we’ve covered in the past?

Language is incredibly important to contemporary psychology and philosophy. Do you agree with Skinner’s assertion that “etymology is the archeology of thought”?

Is this a topic you’d like to discuss more in future?

The response to Essay Club has been amazing so far. Thank you all for your support and comments. If you enjoyed this, I invite you to return in two week’s time to discuss In Praise of Silence by Vernon Lee.

Please consider subscribing, and if you have suggestions for future Essay Club picks, feel free to share them in the comments.

You can vote for the next essay pick below:

Religion, Heuristics, and Intergenerational Risk Management (PDF) by Rupert Read & Nassim Nicholas Taleb

A proper understanding of religion through the lens of rational philosophy—not a collection of senseless rituals, but a set of practices that emerged to provide quick rules for good living and protection against intergenerational risks.

My Own Life by David Hume

A brief reflection on life as a writer and philosopher, written by one history’s greatest thinkers. Thanks to Jonah Dunch for the recommendation!

Myth, History, and Pagan Origins by John Michael Greer

An essay by America’s foremost druid on the similarities and differences between history and myth, ideology, and the myth of moral dualism—all through the lens of modern Paganism.

Fragments From an Education by Christopher Hitchens

Many of you will know Hitchens as one of the ‘four horsemen’ of New Atheism. In this essay he reflects on his time in English boarding school, and concludes that there might still be something worth preserving in this old system.

Added by author DA for clarity.

I am finally getting around to reading this essay, Dan--or rather, I read your Summary, as the essay itself looked intimidating. Your summary was excellent though, and I don't feel like I have missed anything other than hearing things in Skinners own words.

Q1: What do you make of Skinner’s core thesis? Can (or should) all human cognition be described in behavioural terms?

I don't think so. One of the things that the Enlightenment brought us is the Scientific Method and Empiricism. I don't think Empiricism can capture the sum of all human experience, and anecdotal evidence is required. I think this is why there are many hypotheses and tests and experiments about a humans interior life, and yet human behavior can be quite intuitively understood between fellow humans who have known each other a long time. There's no need to look for stimuli or patterns.

I think the "babies are random-process generators" trying out every combination until they try something that gets a reaction is overblown. It feels like trying to retcon an explanation for a phenomenon we observe. I think also that a spiritual component is missing--namely because this is the lens through which I view the world. Behavior alone cannot explain everything human, and our souls and grace work in our lives from the moment of our conception. We are unique persons from the very beginning, and I truly believe that some aspects and idiosyncrasies that result from that cannot be explained.

Q3: Language is incredibly important to contemporary psychology and philosophy. Do you agree with Skinner’s assertion that “etymology is the archeology of thought”?

I think this is a really interesting idea but again, I feel like he is working backwards. He sees a phenomenon and is inventing an explanation for it, rather than really observing anything unique. Language is as much a function of time as it is of place, and encoded into etymology is a context that we cannot access except obliquely. So I think to say that we adopt terms that resemble physical phenomena is to ignore the context of words. I would say especially--the existence of synonyms becomes problematic. Why would not people in the same culture at the same time use the same word? What did the study of etymology look like for the ancient romans? The ancient greeks?

Q4: Is this a topic you’d like to discuss more in future?

Yes! This is really interesting, and especially it's something I'm not very knowledgeable about so it would be interesting to learn through these essays some different schools of thought on the subject!

Thanks Dan! This was fantastic!

I’m most struck by the ‘etymology is the archaeology of thought’ concept. I’ve long been fascinated by the development of language, from when I first got into Tolkien, through today as I observe corporate jargon and its odd poetics. The idea that the roots of our behavior can be excavated by looking at how we use which words to describe it is fascinating to me.