God Help Us, Let's Try to Understand the Self-Memory System

Conway and Pleydell-Pearce's influential model explained (probably)

Oscar Wilde famously proclaimed, through his character Algernon Moncrieff, that “the truth is rarely pure and never simple.” Never has this been more true than with Conway and Pleydell-Pearce’s Self-Memory System, a model of autobiographical memory that, unfortunately, is of central importance to the Mind & Mythos project.

I’ve spent the past few months trying to get my head around this thing. I’ve read several journal articles and a book chapter dedicated to the topic, and after all of this I can safely say that I kind of get it. Maybe. It’s hard to know whether my struggle is just due to my own limitations or the authors’ incomprehensible writing, but it hasn’t been easy, and I can’t promise I’ve gotten everything right.

Nevertheless, we’re doing this. Today I’m going to attempt to explain Conway and Pleydell-Pearce’s Self-Memory System. If this doesn’t interest you, jump ship now. Otherwise, tie yourself to something sturdy and read on.

What is Autobiographical Memory?

Before we discuss the Self-Memory System (SMS) itself, we first need to know what’s meant by ‘autobiographical memory’. Autobiographical memory refers to a person’s memory of their own personal history and experiences. Memories you have of your childhood, your time at school or work, your relationships, your achievements and failures—anything you’ve done, any experiences you’ve had—fit under this label. What this doesn’t include is purely factual information such as the names of famous figures, details of historical events, how to add and subtract, or how to cook lasagne—although, of course, we might have autobiographical memories tied to our knowledge of these facts.

Conway and Pleydell-Pearce suggest that autobiographical memories are recorded by the brain at three levels of specificity:

Event-Specific Knowledge, the basic sensory and perceptual building blocks of a memory, e.g., specific sounds, physical sensations, visual images, feelings;

General Events, which include single extended events (my 2022 trip to Europe) and repeated events (times I’ve visited Melbourne);

Lifetime Periods, broad autobiographical periods organised temporally or thematically, e.g., ‘high school days’, ‘university days’, ‘first dates’, ‘overseas trips’.

A key principle of the SMS is that autobiographical memories are not permanent, factual records of historical events. That is, they’re not simply recorded verbatim and then replayed later, but are constructed and re-constructed—constructed from the most important information at the time a memory is created, and then reconstructed in a similar way at the time of recall. Recalling a specific autobiographical memory, then, is less like picking up a novel and reading it cover-to-cover, and more like putting together a scrapbook from numerous magazine clippings.

Now consider this passage from Conway et al.:

“The SMS model postulated that autobiographical memories were the transitory mental constructions of a complex goal-driven set of control processes collectively referred to as the working self.” - The Self and Autobiographical Memory: Correspondence and Coherence

“Transitory mental constructions” essentially refers to the stuff we discussed above. But what are these ‘goal-driven control processes’? What’s the ‘working self’? This brings us to the SMS proper. Now that we have a basic understanding of autobiographical memory, let’s explore how the Self-Memory System bridges the gap between memory and the Self.

The Self-Memory System (SMS)

The SMS is a model that describes the relationship between our autobiographical memories and our self-concept. It has three main components: the Episodic Memory System, the Long-Term Self, and the Working Self, which mediates between the former two. I’ll describe each of these in due course. Before I do, though, we need to discuss two important concepts: adaptive correspondence and self-coherence.

Adaptive Correspondence (Factual Accuracy) vs. Self-Coherence

Consider this problem: whenever we create a new memory, our brains are tasked with striking a balance between ‘adaptive correspondence’ and ‘self-coherence’. Adaptive correspondence is essentially how well an autobiographical memory corresponds with reality (for simplicity’s sake, let’s just call this factual accuracy). A memory that is factually accurate is one that represents the remembered event as it actually occurred. Self-coherence is about how well our memories match up with our view of our Self. A memory that is self-coherent will be constructed or interpreted in a way that shows us acting (or intending to act) in-line with our self-concept—for example, someone who views themselves as a kind, compassionate person might recall giving a homeless person money, even if in reality they never did so. When we record or recall a memory, it’s constructed in a way that either preserves the factual accuracy or the self-coherence of the event. Sometimes it preserves both, of course, but there’s often a trade-off between the two.

Why is this? I’ve described elsewhere how humans are essentially goal-driven creatures, and when it comes to memory, it’s no different. A core assumption of the SMS is that autobiographical memories are constructed to facilitate goal attainment. In the short-term, our goals are generally quite practical—make breakfast, drive to the shops, email the boss—and factually accurate memories are needed to keep track of our progress. But in the long-term, once these goals have been achieved, the memories attached to them stop being useful. At this point we either forget them, or their purpose becomes one of supporting our longer-term goal of maintaining a consistent sense of Self. If this corresponds with reality, then great—nothing changes—but if I think of myself as someone who’s health-conscious and assertive, and I remember too many instances of eating unhealthy snacks or avoiding emailing the boss, my concept of Self is going to suffer. I’ll soon face a major identity crisis. To avoid this happening too frequently, the Working Self acts as a kind of information filter, and ensures that our recollection of events is consistent with our Conceptual Self.

I’m starting to throw around some unfamiliar terms now, so let’s stop and take a closer look at the three components of the SMS: the Episodic Memory System, the Long-Term Self, and the Working Self. The usual rules about modelling human behaviour apply here—the map is not the territory, etc.—but for those interested, Conway et al. do make a compelling case that these categories map quite well onto human neurobiology. I won’t cover this here, but you can read more about it in the links at the end of this post.

The Episodic Memory System

The Episodic Memory System is arguably the easiest component of the SMS to understand. This is the part that holds specific, factual details about our experiences in the short- to medium-term—sensory and perceptual information, what we thought and felt at the time, what was objectively observed. In other words, Event-Specific Knowledge.

According to Conway et al., we retain this information so that we can make effective progress toward our (primarily short-term) goals. Without an accurate recall of what we’ve done before, we can’t know our next step. Without this, it would be impossible to achieve anything beyond the most basic of tasks. Once these tasks are achieved, though, the memories often become less relevant—at this stage the SMS either allows these memories to be forgotten, or they are integrated into the Long-Term Self.

Put simply, the Episodic Memory System is the part that fulfills our need for factual accuracy in the short-term.

The Long-Term Self

In the words of Conway et al.:

“[The Long-Term Self] contains the knowledge required by the Working Self to organise and instantiate active goal processes… the Long-Term Self consists of the Autobiographical Knowledge Base, and the Conceptual Self.”

To understand what this means, let’s work backwards. The Long-Term Self consists of two parts: the Autobiographical Knowledge Base (AKB) and the Conceptual Self.

The AKB is the more factually accurate part of the Long-Term Self. It holds autobiographical knowledge about Lifetime Periods and General Events, including experiences that occurred over an extended period of time, repeated events, and events organised temporally or thematically. Factual information retained by the Episodic Memory System that remains relevant to our long-term goals is held here, and this information is used to inform both our ongoing goal attainment and the development of our Conceptual Self.

Conway et al. suggest that the AKB might also hold another kind of information: the Life Story Schema. The Life Story Schema “consists of even more global personal history information than lifetime periods”, and draws on socio-cultural narratives to inform a person’s understanding of how their own life story fits within the wider culture. Conway et al. don’t say too much about this, only that it includes “generalizations about ‘life chapters’ and themes, as well as connections to cultural myths and narrative structures”.

In contrast with the fact-focused AKB, the information held by the Conceptual Self is much more abstract. Conway et al. suggest that the Conceptual Self “consists of abstracted knowledge about the self, contextualised in terms of a person’s life by autobiographical knowledge and ultimately grounded in episodic memories of specific experiences”. Stated differently, the Conceptual Self is our understanding of the kind of person we are, generally speaking, based on what we remember of our actions and experiences. A person who grew up on a farm and now works as a builder might think of themselves as ‘hardworking’ and ‘practical’; a person who did well in school and went on to become an academic might think of themselves as ‘studious’ and ‘intellectual’.

The Conceptual Self has an interesting two-way relationship with the AKB. Obviously, the Conceptual Self needs to have some grounding in actual autobiographical experiences; a person who’s never read a book in their life couldn’t realistically view themselves as ‘intellectual’. But a person’s Conceptual Self also influences the kinds of memories that are more readily generated by the AKB. A person who thinks of themselves as ‘compassionate’ will have a much harder time recalling times when they were cruel or impatient.

The Conceptual Self also seems to change over time. For example, at age 30, I think of myself as a very different person to my 15-year-old self. As a teenager I was more moody, I had different interests, different beliefs. At age 30, I like to think that the extra 15 years of experience has made me more mature, more knowledgeable, more emotionally stable. What’s interesting about this is that the memories I have of those earlier years haven’t changed, but my interpretation of them is very different—I now view many of my most important memories in a very different light.

To sum all of this up: the Long-Term Self is the part of the SMS that organises the various memories and self-concepts that contribute to our longer-term goals. Some of these goals are quite practical, but many are more abstract, having more to do with the maintenance of a consistent identity and life narrative. These parts interact with one another in complicated ways, with the AKB informing the kind of Conceptual Self that can realistically be generated, and the Conceptual Self influencing which autobiographical information is more readily accessible by the AKB. All of this changes over time, depending on the long-term goals that are most relevant over the course of our lives.

The Working Self

One of the main problems faced by the brain is one of goal management. That is, identifying and prioritising our goals, ensuring that they’re compatible and realistic, and coordinating our actions in order to achieve them. This isn’t a simple task. Our lives are motivated by many goals, often multiple at once, all of varying complexity and importance. We now know that our short-term goals rely on information drawn from the Episodic Memory System, and our long-term goals draw from the Long-Term Self. Conway et al. argue that there’s a third part, the Working Self, that coordinates all of this.

The Working Self is always active. As we go about our days, and especially when we experience something new, the Working Self is there making sense of it all. It does this by comparing what’s currently happening to what we already know (our memories) and what we hope and expect will happen (our goals). Depending on our ‘goal-activity status’, i.e., the goal that’s active and most salient to us at the time, we might interpret the current situation in a more factual manner (drawing upon information from the Episodic Memory System and/or the AKB), or in a way that’s informed more by our self-concept (the Conceptual Self). The outcome—our response or non-response to the situation at hand—will depend upon the Working Self’s interpretation of events.

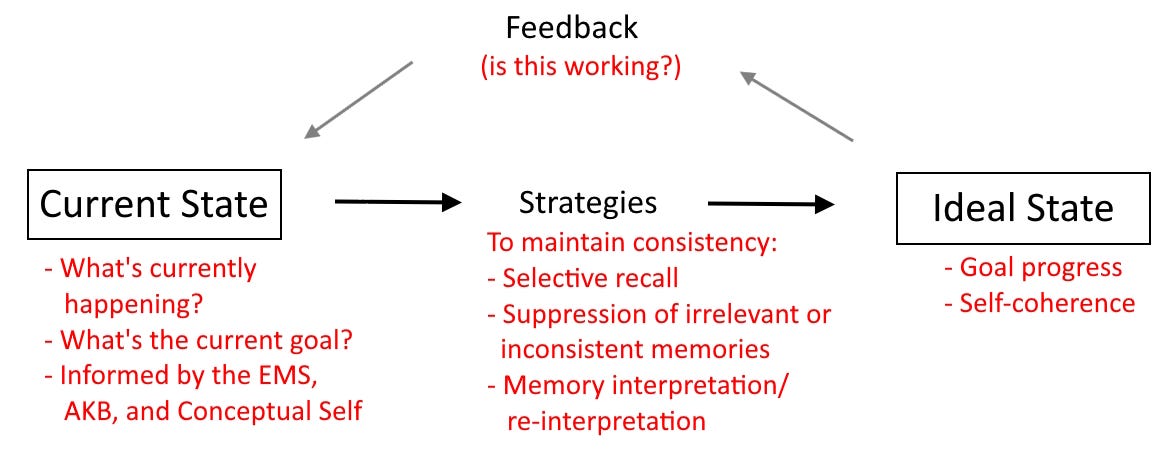

If this is sounding familiar to you, it should! What I’m describing is basically a cybernetic system. I’ve talked about cybernetics before in relation to human personality and psychopathology, so it should come as no surprise to find that the cognitive systems governing autobiographical memory and self-identity function in a similar manner. The Working Self is, in essence, a cybernetic system.

In any given situation, the Working Self generates a working model of the present moment, and compares this with the currently active goal (the goal that’s most important and relevant to the situation), as well as autobiographical information drawn from the Episodic Memory System and the Long-Term Self. If nothing about the current situation conflicts with our expectations of goal attainment or our sense of Self, all is well. We go on as usual, perhaps even eventually forgetting the event entirely. If there is a conflict, alarm bells ring—we feel anxiety, sadness, fear, or anger—and then the Working Self jumps into action.

The Working Self is the gatekeeper between our conscious mind and our unconscious memories. Its job is to reduce any discrepancy between what’s currently happening and what’s already known, so that we can live our lives with relative certainty. It has a few tricks1 to do so (most of which can be reasonably described as self-deception), but if this mental wizardry fails, and reality continues to not meet our expectations, the Working Self brings this to our conscious attention. At this point, it becomes necessary to either reevaluate our goals and plans, or (if things get really out of hand) reevaluate our concept of Self entirely. In the latter case, this typically involves reaching back into our past and reinterpreting old actions in new ways that support a more robust picture of oneself.

The Working Self, then, is best understood as the part that works to maintain consistency between current experience, our goals, and our sense of Self. It’s relatively conservative, and works hard to maintain our pre-existing goals and narratives, but if this becomes unviable it also works hard to find or reinterpret memories that can re-establish a sense of stability. All of this relies on information drawn from the Episodic Memory System and the Long-Term Self, which we can now think of as something akin to a ‘filing system’ for the Working Self.

Putting It All Together

Is this making sense so far, or is it all nonsense? To make things a little more clear, let’s try removing the jargon and simply talk about the basic concepts.

There’s a part of our brains that keeps short-term, factual autobiographical details; a part that keeps long-term, factual autobiographical details; and a part that maintains a long-term, stable, conceptual understanding of our Self. These aren’t particularly ‘active’ parts—think of them as a kind of filing system. There’s also a part that plays an active role in deciding what information about our experiences should be kept and how it should be interpreted (both in the moment and upon recall), which works to coordinate all of this information with our short-term and long-term goals.

When we experience something new, factual details are recorded, and an interpretation is attached. This interpretation is made in relation to our goals—either the facts of the situation reflect progress towards our short-term or long-term goals, or they don’t; either the facts support our broader conceptual understanding of ‘who I am’, or they don’t. Irrelevant or inconvenient information is more likely to be forgotten, especially in the long-term, because over time, the long-term goal of identity stability supersedes all else. If we can’t maintain a stable sense of Self, everything else falls apart.

At a later date, a memory of our experience might be triggered in response to the activation of a relevant goal. When this happens, the memory isn’t recalled verbatim, but pieced together from all the fragmented sensory-perceptual, factual, and conceptual information stored in our file drawers. If it hasn’t been too long since the event occurred, the re-constructed memory will probably still be fairly accurate—short-term goals tend to rely more upon factually accurate information—but if it’s been a long time since the event, there’s a good chance that the memory will be somewhat distorted to fit better with our self-concept. The end result is a person with a slightly self-serving but internally consistent life narrative, who is still able to achieve his or her practical goals.

So—that’s the Self-Memory System! I trust that all of this made sense, and I’ve left you with no further questions. I’ll be talking about the Self-Memory System again soon in my upcoming series The Stories We Tell (it’s coming soon, trust me bro, please, it’s coming), but probably not using the explicit terminology I’ve included in this post, so this will be here if you get confused and need more background.

Thanks for reading—if you enjoyed this, I invite you to subscribe below for more. If you didn’t, consider sharing it with someone who will!

Further Reading

Conway & Pleydell-Pearce (2000), The Construction of Autobiographical Memories in the Self-Memory System

Conway, Singer, & Tagini (2005), The Self and Autobiographical Memory: Correspondence and Coherence

Conway (2005), Memory and the Self

Conway, Justice, & D’Argembeau (2019), The Self-Memory System Revisited: Past, Present, and Future (from The Organization and Structure of Autobiographical Memory by John Mace)

Wilde (1895), The Importance of Being Earnest

These ‘tricks’ include filtering which memories can and can’t be accessed (selective recall and memory suppression), determining how new memories should be interpreted, and determining whether a new memory should be remembered at all. In the latter case, forgetting might simply occur due to irrelevance/unimportance, but it can also happen if an experience conflicts too strongly with our internal narrative and sense of Self.