The Stories We Tell: Myth, Memory, and the Self

The Stories We Tell, Chapter 1

When someone asks you to “tell me about yourself”, what do you say?

Maybe you start with your social roles. “I’m an architect”, “I’m a father”, “I’m a member of the Rotary Club”. You might then tell them a little about your history. “I’m from Sydney”, “I lived in Germany for ten years”. If the conversation continues, you’ll eventually start to touch on more personal topics. You might share some of your hopes, hobbies, values, achievements, even some of your fears and failures. Over time, what will emerge is not just a list of facts, but a story—a story that tells the listener who you really are, and what matters to you.

I’ve previously suggested that stories are an important part of human psychology. Our brains use cybernetic systems to organise our knowledge and drive us to action, but we don’t consciously think in this way. It’s too cold, mechanistic, and inflexible. Stories are different—through storytelling we can catalogue and share a great deal of personal information in a way that is both efficient and emotionally engaging. Consider your own story. What challenges have you faced? What accolades have you received? Who are the key players in your life, and how have they shaped you? These are the kinds of questions that define us. They give us our why, without which our goals would lack purpose.

In this new series, The Stories We Tell, I hope to convince you of the importance of stories. I believe that we tell stories not just for entertainment, but to gain a better understanding of ourselves and the world around us, and to give our lives meaning. In this first chapter I’ll focus on the stories we tell about ourselves. In future chapters I’ll talk more about collective storytelling, including the myths and grand narratives that shape whole civilisations.

Memory and the Self

Let’s start with what we already know. One of the take-home messages of my series On Personality and Psychopathology was that humans are goal-driven creatures. We’re motivated by internal urges that compel us to do things like avoid danger, pursue pleasure, seek new opportunities, and maintain good relationships. We’re all ultimately motivated by the same things, but our priorities differ, depending upon our innate preferences, upbringing, and life circumstances. We call a person’s individual expression of these internal urges their personality.

Of course, a person is more than just how they act and what motivates them. People have histories, and in my recent post on Conway and Pleydell-Pearce’s Self-Memory System, I showed how these histories—our autobiographical memories—interact with our goals and sense of Self. The basic idea is that, when a person encounters something new, they record the details of the event in their mind and attach an interpretation of the experience. This interpretation is always made in relation to one’s goals—either the facts of the situation reflect progress toward one’s short-term or long-term goals, or they don’t; either the facts support one’s broader conceptual understanding of ‘who I am’, or they don’t. Irrelevant or inconvenient information is usually forgotten, especially in the long-term, because the long-term goal of identity stability (which sometimes clashes with the raw facts) is more important. Without a stable sense of Self, we simply cannot function.

So our self-concept is grounded in our autobiographical memories. We know who we are because we remember ourselves being that way. And not just once, but repeatedly, consistently, and in many different situations. This suggests that we hold a timeline of our experiences in our minds, one that is skewed in favour of achieving our future goals, from which we can draw conclusions about who we are and how we came to be that way. We call this our personal narrative, or life story.

Psychologist Dan P. McAdams, who has dedicated his career to the study of life stories, articulates all of this very well. He tells us:

“In late adolescence and young adulthood, people living in modern societies begin to reconstruct the personal past, perceive the present, and anticipate the future in terms of an internalized and evolving self-story, an integrative narrative of self that provides modern life with some modicum of psychosocial unity and purpose. Life stories are based on biographical facts, but they go considerably beyond the facts as people selectively appropriate aspects of their experience and imaginatively construe both past and future to construct stories that make sense to them and to their audiences, that vivify and integrate life and make it more or less meaningful.” - Dan P. McAdams, The Psychology of Life Stories (2001)

McAdams argues that narrative identity is the crucial third piece of the personality puzzle. Traits and character adaptations (which I’ve discussed elsewhere) are useful for describing and explaining how personality works, but trait descriptors are fairly generic when used out of context, and even context-dependent character adaptations offer only a vague picture of the Self. By drawing upon our unique life experiences, narrative identity allows our traits and character adaptations to become personal to us.

Narrative Identity and the Personal Myth

Narrative identity is “a person’s internalised and evolving life story, integrating the reconstructed past and imagined future to provide life with some degree of unity and purpose”1. It is a product of the human mind’s ceaseless desire to pattern-match and generalise; by drawing upon dominant cultural narratives, our interpretations of our experiences, and our imagined future, we are able to construct a coherent personal myth about who are and where we are going. This personal myth is something that is uniquely human—other animals have traits, and some even have character adaptations, but only humans can mythologise.

We see the first glimmers of narrative identity in childhood. Studies have repeatedly shown that, as children begin to speak, the ways in which parents respond to their children’s stories influence their narrative development later in life. Parents who encourage detailed elaboration and reflection, who focus on emotion, causation, and overall meaning, raise children who are better at constructing more complex and emotionally compelling personal narratives in adolescence and beyond.

In our teenage years, the writing of the personal myth begins in earnest. We start to see ourselves as unique individuals, no longer beholden to the narratives instilled by our parents. For most people in the West, adolescence and young adulthood are periods of significant self-exploration; our stories begin to take on a more ideological tone, and we come to define ourselves either in terms of, or in opposition to, dominant social groups and cultural narratives. Through our interactions with friends and other important figures, we process, interpret, and re-interpret our life story, eventually forming a coherent personal myth. This story continues to develop and change throughout our adulthood, even into very old age.

What does a fully developed personal myth look like? In his 1993 book The Stories We Live By, McAdams discusses the various findings that have emerged out of his research on life stories. One of his key discoveries is that people narrate their personal myths using many of the same basic elements found in well-written fiction. For example, personal myths have settings, in both the physical sense and in the sense of a ‘social milieu’; they have characters, including a protagonist, antagonists, and ‘sidekicks’; they have a recognisable tone, such as optimism, mistrust, resignation, or curiosity; they have major themes, such as the quest for power, love, or freedom; and of course, a well-constructed personal myth will have an overarching plot, including conflicts, story ‘beats’, and an imagined conclusion.

When it comes to personal myths, these elements are more than mere aesthetic preferences. McAdams and colleagues have found that people whose stories have a high degree of narrative coherence, and which feature them heroically overcoming difficult circumstances, tend to experience higher levels of happiness and a stronger sense of meaning in life. On the other hand, stories that are incoherent, that feature the narrator succumbing to their suffering, or that never resolve the narrator’s difficulties2, are associated with worse outcomes. We only have so much control over the circumstances of our own life, but when it comes to maintaining good mental health, what we focus on and the interpretation we attach to our experiences (the themes and tone) are far more important than the experiences themselves (the setting and plot). A well-told personal myth can fill us with joy and a powerful sense of purpose, but a badly told myth can be debilitating, even fatal.

What this means in practice is that the way we tell our story matters. Earlier in this essay I asked you to consider your own story—now consider the way in which you tell it. If you’ve faced great challenges in your life, how do you interpret these experiences? Do you see yourself has having overcome these challenges, or succumbed to them? What about your failures? Do you continue to kick yourself for your mistakes, or do you acknowledge and learn from them? If you’ve been let down by the people around you, do you take that to mean that there are no trustworthy people in the world, or that there are simply a few bad apples (best avoided in future)? Our answers to these questions say a lot about our story and its eventual conclusion. If your own narrative is starting to sound more like a tragedy than a comedy, it might be time for a rewrite.

Rewriting Your Personal Myth

All of this psychological theory is very interesting, but what can we actually do with it? How does somebody transform the mundane events of their life into a myth so powerful that it generates meaning and purpose? For what follows, I’ve drawn from research on narrative identity, narrative approaches to therapy and personal growth, as well as my own experience as a practicing psychologist and human.

To begin, you need to have a clear idea of what you’re working with. The first step, then, is to know your own story. Take the time to write it out—spend a few days, even a few weeks if needed—and include all of the most important events and details, all the way from birth through to the present day.

Once you’ve laid out the narrative of your life, and you’re certain that you’ve included every important detail—throw it away! Now you’re going to write it all again, but this time with a focus on the feelings and interpretations you attach to these events. For personal myth-making, the raw facts of your grade twelve Formal (‘Prom’ in American) are less important than what that event meant for you. For example, how did you feel that night and why? Do you recall this being a good or bad experience, overall? What did you learn from it?

As you write and re-write your story, pay careful attention to any themes that emerge, as well as the overall tone of the narrative. Is yours a tragic tale of repeated losses and failures? Do you walk away with feelings of hopelessness, anxiety, and anger? Perhaps yours is a more uplifting story, one of progression and hard-won wealth that leaves you feeling satisfied and self-assured? Often the themes will be obvious, but it’s not always so clear. If you find yourself in this position, try working backwards—reflect on your life as it is right now, consider how you feel most days and why, and see whether you can identify a pattern of similar experiences over the course of your life.

You should now have a clear narrative laid out before you. If you don’t, it’s arguably even more important that you follow the next steps. Either way, you are now faced with a choice: do you accept this story as it is, or try to change it?

If you want to change your story, you must now turn a critical eye on what you’ve written. Consider the interpretations you’ve made about your experiences—are they true? Are they useful? Are you holding yourself to the same standard as you do others? Does thinking in this way lead to better outcomes? If your answer to any of these questions is no, consider alternative explanations. Instead of explaining away abuse or neglect with “I was a bad kid who deserved it”, try “I had bad parents who were unwilling or unable to meet my childhood needs”. If after a breakup your response was “I’m eternally unlovable”, consider instead that you were “just not a good match”. Then seek out memories that have been ignored, experiences that challenge these assumptions and provide a more balanced perspective. As you work through your past, you’ll start to notice common generalisations—e.g., ‘I’m a failure’, ‘the world is unsafe’, ‘nobody can be trusted’—that simply don’t hold up to scrutiny. The core memories associated with these ideas can then be rewritten as obstacles that were overcome, and that made you stronger, wiser, and more resilient.

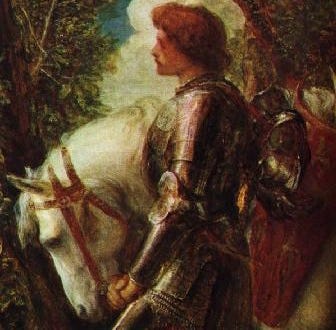

If your problem is one of narrative coherence, it might help to use a template, at least to begin with. Benjamin Rogers and colleagues have identified a 7-part ‘Hero’s Journey’ structure that is common to the stories of many people who report higher life meaning and emotional wellbeing. Even if you view your own life as too mundane to be called ‘heroic’, identifying these seven elements—the Protagonist, the Shift, the Quest, the Allies, the Challenge, the Transformation, and the Legacy—can help you to construct a myth that makes sense and clarifies your life’s purpose.

The final step in rewriting your personal myth is to seek out opportunities to reinforce your myth. Tell and re-tell your story to others, try new activities in which you can embody the strengths and virtues of your story’s Hero, and surround yourself with people who’s own stories and values match your own. Storytelling is fundamentally a social activity—I will have a lot more to say about this in chapter two, but for now, consider the impact that having your story recognised by others might have on your sense of Self.

Final Thoughts

Stories are fundamental to the way that we understand ourselves and generate meaning from our experiences. Like a well-written novel, a good life story can fill us with joy, satisfaction, and a lust for life. The personal myth is just one of the types of stories that can impact us in this way. In the next chapter of The Stories We Tell, I’ll introduce another kind of story, the cultural myth, which I believe provides many of the basic ingredients for our stories. Like the personal myth, the cultural myth organises our collective memories, and can provide a profound sense of meaning and a collective identity for whole groups of people.

Thanks so much for reading! If you enjoyed this, please share your thoughts in the comments, subscribe, and if you have the means, consider upgrading to a paid subscription. This essay has taken a lot of work—I’ve spent the better part of a year drafting and re-drafting it in different forms—so knowing that people enjoy my work helps me to stay motivated. Either way, the next instalment will be published soon. Until then…

Further Reading

McAdams (1993), The Stories We Live By

Esterling et al. (1999), Empirical Foundations for Writing in Prevention and Psychotherapy: Mental and Physical Health Outcomes

Conway & Pleydell-Pearce (2000), The Construction of Autobiographical Memories in the Self-Memory System

McAdams (2001), The Psychology of Life Stories

Conway, Singer, & Tagini (2005), The Self and Autobiographical Memory: Correspondence and Coherence

Fivush, Haden, & Reese (2006), Elaborating on Elaborations: Role of Maternal Reminiscing Style in Cognitive and Socioemotional Development

McAdams & McLean (2013), Narrative Identity

McLean & Syed (2016), Personal, Master, and Alternative Narratives:

An Integrative Framework for Understanding Identity Development in Context

Rogers et al. (2023), Seeing Your Life Story As a Hero’s Journey Increases Meaning in Life

I often see clients with trauma, and I’ve come to view PTSD as fundamentally an inability to ‘resolve the story’. My job as a therapist is to help the person rewrite their story in such a way that it both makes sense, and eases any guilt/shame/regret/grief left over from the event.

I absolutely loved this Dan - thanks for sharing it! So much power in rewriting personal myths. Have you ever done past, present or future authoring programs by Jordan Peterson?