Psychology Finally Has a Unifying Framework

Gregg Henriques' Theory of Everything

Many scientists spend their whole lives digging deeper and deeper into the minutiae of their chosen sub-specialty. It’s thankless work. Millions of journal articles are published every year, only to be read by a handful of like-minded experts. Occasionally something like a global pandemic happens, and a lucky few become household names overnight. Some scientists even stumble upon something groundbreaking, like penicillin or the theory of relativity, and get their names added to the history books. Most, though, remain relatively obscure, and are quickly forgotten by all but their closest friends, colleagues, and family members.

This sounds quite cynical. I don’t mean it to be. This is just the way of the world, and without the worker-bee scientist doing this incremental labour to fill the gaps in our knowledge, science couldn’t progress. It’s truly important work. But I’m a big picture guy, so when I step back and think about how much work is being done for so little gain, I have to wonder: what does it all mean?

Gregg Henriques, a clinical psychologist and researcher at James Madison University, is someone who has tried to find an answer to this question. Over the past two-and-a-half decades Henriques has been developing a comprehensive ‘theory of knowledge’ which brings together ideas from fields as distant as physics, biology, and social science. It’s an incredibly ambitious project. What began as an attempt to unify psychology has been gradually expanding into a much broader ‘theory of everything’, and one wonders how far he can take it. But I love a grand theory, and I think this particular theory gets a lot right, so today I invite you to join me on a deep-dive into Gregg Henriques’ Unified Theory of Knowledge.

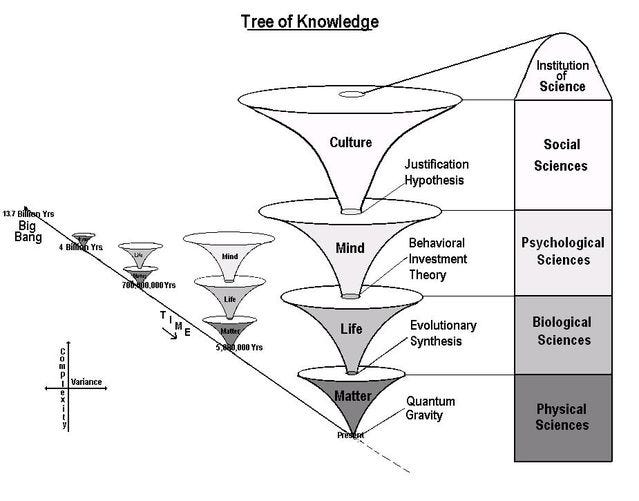

Foundations: The Tree of Knowledge

Henriques’ theory assumes that the physical laws of the universe pre-dated the emergence of biological, psychological, and cultural phenomena. This is the standard scientific view. Scientists estimate that the universe is about 14 billion years old; Earth is only 4.5 billion years old, has supported various forms of life for about 3.7 billion years, and has been home to animal life for, at best, 800 million years. Intelligent, minded animals emerged even later, and homo sapiens—distinguished as much by their culture as their intelligence—have only existed for about 200-300 thousand years. In this we see a clear progression from matter to life to mind to culture, which Henriques describes as an ‘evolution of complexity’.

This process occurred in four consecutive stages. Each stage began at a historical ‘joint point’, a crucial moment in which something fundamental about the nature of reality changed to allow for a radical leap in the complexity of matter on Earth.

Stage 1: In the beginning, what we now call the universe was a singularity of pure Energy. The first joint point was the Big Bang, where, through a series of complex physical processes, this Energy slowed and cooled into stable chunks of Matter.

Stage 2: The second joint point was the moment when Matter came alive. Over hundreds of millions of years, changes in the Earth’s chemical composition led to the emergence of “self-replicating chemical machines”1 (chiefly ribonucleic acid, RNA) which, under Darwinian selection pressures, gradually evolved into large-scale, multicellular organisms—Life.

The first two stages aren’t controversial. Most scientists would agree that these developments were crucial to the eventual emergence of human life. The third and fourth joint points, however, are where Henriques’ theory comes into its own.

Henriques suggests that Mind—the ability to think, perceive, remember, imagine—emerged in animals as a consequence of their capacity for movement. As animals began to move around, they came into contact with different environments, opportunities, and threats, and they needed to find a way to handle these new situations. Over time, they evolved internal control systems by which they could modulate their interactions with their environments (i.e., to pursue goals and avoid threats in efficient and effective ways). This marked a new era in the evolutionary timeline. Organisms were no longer entirely dependent on genetic programming for their survival; they could now “generate new behavioural outputs in response to novel environmental stimuli”2, meaning they could understand and adapt to the changing world around them. This, the evolution of the nervous system, was the third joint point.

The fourth joint point was the emergence of self-awareness in humans, and the subsequent need to justify our actions to others. This goes beyond mere intelligence. Many apes have demonstrated intelligent use of tools, and countless animals communicate by vocalising. What sets humans apart from other animals is our ability to ask why. Why did I do that? Why did you do that? Being social animals, we quickly realised that our actions could affect and be questioned by others. If the consequences of our actions were unpleasant for others, we needed to give a good reason for doing them. Over time, this need for justification led humans to develop elaborate systems of morality, mythology, philosophy, religions, laws, and scientific theories to answer these difficult questions. We created, in a word, Culture—“shared justification systems based on symbolic language”3.

As a psychologist, the third and fourth stages are, naturally, the most interesting to me. They are also the most controversial, in that they are not widely accepted as pivotal historical moments like the Big Bang or the beginning of the evolutionary timeline. I think Henriques is correct, though, and I think he offers a compelling case for his theory. The argument for joint points three and four rests on two ideas: Behavioural Investment Theory and the Justification Hypothesis.

The Third Joint Point: Behavioural Investment Theory

According to Behavioural Investment Theory, the nervous system evolved to ensure that animals could achieve their adaptive goals (chiefly, survival and reproduction) in ways that were maximally energy-efficient. This means that every basic function that we associate with the nervous system—sensory processing, memory, learning, emotion, behaviour, etc.—is in some way involved with this process of goal-driven energy investment. This Behavioural Investment System (BIS) is genetically hardwired, an adaptation built through natural selection over many generations, but it is also incredibly flexible, able to adapt to the changing environment and to new challenges encountered throughout an animal’s life.

To demonstrate how the BIS handles everyday events, Henriques asks his readers to imagine sitting down to watch TV at the end of a hard day’s work. Triggered by an Oreo cookie advertisement, you feel a strong desire for a glass of milk, and then:

“A small calculation takes place—almost subconsciously—as you decide whether it is worth the effort to get up and pour yourself a glass. Finally, the thirst wins out. You pull yourself up and head over to the refrigerator. But scanning the contents you find no milk, resulting in a glance over at the trashcan, where you see the empty container. Feelings of irritation follow the interruption of your goal. The thought briefly enters your mind to head to the store, but it is quickly quashed—that would clearly require too much time and effort. You settle on a glass of orange juice, with mild feelings of annoyance.”

Before we take an action, we need to feel that any potential benefit of that action will outweigh the effort required. In Behavioural Investment Theory terms, the expected gain must outweigh the expected energy investment needed to achieve it. In this case, the effort required to get a glass of milk is deemed worthwhile—right up until we realise that there is no milk left, at which point we feel (literally) frustrated. Notice my use of the word feel here. This is not a rational process. Much of the BIS’s work is impulsive, pre-rational, and feelings-driven. Also notice that the BIS is quite flexible, and willing to accept ‘good enough’ outcomes—something is better than nothing, after all, so we accept orange juice as a reasonable substitute for milk.

In his 2011 book, A New Unified Theory of Psychology, Henriques breaks down Behavioural Investment Theory into six foundational principles:

The principle of energy economics: “Animals must, on the whole, acquire more work-

able energy from their behavioral investments than those behaviors cost.”

For an animal to survive and pass on its genes, it needs to take in more energy over the course of its life than it expends.

The evolutionary principle: “Genes that tended to build neuro-behavioral investment systems that expended behavioral energy in a manner that positively covaried with inclusive fitness were selected for, whereas genes that failed to do so were selected against.”

Survival of the fittest. Only those animals with genes that produce adaptive BIS configurations survive to pass them on to the next generation. Genes that produce maladaptive BIS configurations (e.g., that lead to early death or failure to procreate) eventually get extinguished.

The principle of genetics: “Genetic differences result in differences in behavioral investment systems.”

All animals are born with different genetic predispositions and capabilities. In the same way, the default parameters (e.g., risk tolerance level) of the BIS will differ from creature to creature, even within the same species.

The computational control principle: “Represents the central insight from cognitive (or computational) neuroscience, which is the idea that the nervous system is the organ of behavior and that it functions as an information processing system.”

This describes the basic manner in which the nervous system functions. It is essentially a cybernetic/control system, meaning it is a goal-directed system that self-regulates in response to feedback4.

The learning principle: “Behavioral investments that effectively move the animal toward animal–environment relationships that positively covaried with ancestral inclusive fitness are selected for (i.e., are reinforced), whereas behavioral investments that fail to do so are selected against and extinguished.

Operant conditioning principles apply to behavioural investment strategies. Strategies that lead to better outcomes get reinforced, and then get used more often; strategies that lead to worse outcomes get punished, and then get used less often.

The developmental principle: “There are various genetically and hormonally regulated life history stages that require and result in different behavioral investment strategies.”

An animal’s needs and goals will change over the course its life. As a consequence, its behavioural investment strategies will change over time to accommodate these changing goals. For example, a younger, unmarried woman will invest far more energy into romantic pursuits than will an older, married woman.

Readers familiar with biology, cognitive science, behavioural economics, and related fields will recognise these principles. Indeed, very little in Behavioural Investment Theory is new. It’s more like a restatement of a few key, shared presuppositions held by leading researchers in these fields. What Henriques offers is not a new theory, but a simpler, more unified framework for understanding animal behaviour in the broadest sense. For Henriques, it’s the combination of the aforementioned principles that matters. Evolution acting on genetic combinations alone would not be enough for Mind to emerge.

In short, it was the evolution of the nervous system, a behavioural control system capable of achieving complex goals and adapting to challenges, all while ensuring that energy is expended in efficient ways, that initiated the great leap from mindless organisms to intelligent animals.

The Fourth Joint Point: The Justification Hypothesis

The Justification Hypothesis5, put simply, posits that human self-consciousness evolved to allow us to better justify our actions, a need that arose with the development of complex language. This, in turn, led to the emergence of Culture.

To elaborate, language evolved in humans because it provided an outsized advantage to those groups who learned to use it effectively. It allowed us to share important information quickly and easily, it facilitated greater cooperation between individuals, it allowed for the gradual accumulation of information across generations, and it allowed humans to manipulate and make connections between different ideas, which led to technological and cultural advancements. In Behavioural Investment Theory terms, communicating in language significantly reduced the amount of energy people needed to invest to stay alive and birth the next generation.

As we got better at expressing our experiences through language (an ability that was supported by our advanced neurological capacity for self-reflection), we realised that language gave us access to other peoples’ inner experiences as well. This was an important step in the development of human consciousness, but it led to a couple of problems. First, once we understood that actions have intentions, people who acted in unpopular ways—people who were violent, selfish, or who simply did things differently—began to face difficult questions. Anyone who couldn’t give a satisfying justification for an unwelcome act risked social ostracism or even death. This introduced selective pressure into the social arena. Those who learned to use language to negotiate these tricky social dilemmas survived and passed on their linguistic abilities, while those who did not—did not.

Second, we discovered that peoples interests don’t always align. This forced us to find new, socially acceptable ways to deal with differences of opinion. People either had to get better at convincing others to agree with them (rhetoric), or had to find ways to work together to achieve mutually agreeable outcomes (diplomacy). To ensure that our societies didn’t fall apart, we developed rules and customs which could be collectively enforced (law and order), many of which were justified through increasingly elaborate religious and philosophical systems. Put simply, our need for self-justification and collective moral norms forced us to create Cultures, defined by Henriques as “large-scale collective systems of justification”6.

Are you following so far? Now that we’ve covered the basics of Henriques’ Unified Theory, let’s see how well it explains what we already know about psychology.

Psychological Science and the Unified Theory

If Henriques’ is right, everything we know about psychology—every replicable observation made by psychologists since Wilhelm Wundt first opened his lab in 1879—should fit with the Unified Theory. To actually sit down and cross-reference every experiment with the Unified Theory would be a tedious affair, of course, but Henriques does attempt to demonstrate this cross-compatibility by comparing his theory with two well-established models of human cognition: the Dual Processing Model championed by researchers like Daniel Kahneman, and an updated Tripartite Model based on Freudian/post-Freudian ideas.

The Dual Processing Model7 divides human cognition into two distinct information-processing systems. The first, which I’ll call System 1 as per Kahneman, is described with words like fast, nonverbal, implicit, emotional, holistic, and instinctive. System 2 is described as slow, analytic, logical, sequential, conscious, and explicit. Popular psychology books will sometimes link System 1 to our ‘reptilian brain’, which refers to those more ‘primitive’ regions of the brain associated with basic biological functions and emotional impulses (e.g., the basal ganglia and the amygdala). This is an oversimplification, but there is truth to the idea that certain brain regions responsible for our ability to reason, create, problem-solve, and think critically (e.g., the prefrontal cortex) developed later in the evolutionary timeline.

Henriques believes that System 1 is fully explained by Behavioural Investment Theory. Similar to System 1, which relies on older brain regions that are also found in less intelligent animals, the BIS is believed to have emerged prior to our more advanced capabilities for social coordination and complex problem solving. Also like System 1, which seeks quick, ‘good enough’ answers that satisfy our emotions and instinctual urges, the BIS often prioritises behavioural strategies that can achieve immediate gratification of its energy needs. The BIS and System 1 both function in a more direct, ‘experiential’ way, compared with the more self-reflective, meaning-focused System 2. I won’t belabour this point—read Henriques’ work for more—but Behavioural Investment Theory does seem to explain System 1 well, and also accounts for many of the problems that arise from System 1 thinking (e.g., various cognitive biases and other forms of flawed reasoning).

System 2, on the other hand, is a more intelligent beast. It’s capable of rational argumentation, and it can handle social complexity and long-term thinking. These capabilities go beyond those of the impulsive energy-conservation machine described by Behavioural Investment Theory, so they must have evolved to meet a different need than that met by System 1. Henriques believes that the Justification Hypothesis fully explains the existence of System 2. Consider: If a tribe of individuals with enough insight to recognise antisocial behaviour had no way to limit this behaviour, or if tribe members had no way to settle disputes without resorting to violence, the tribe would quickly fall to infighting and eventual extinction. We humans reached a point in our evolution where slow, rational reflection and argumentation became the better option in most situations. System 2, then—as per the Justification Hypothesis—evolved because it became necessary for humans to continue to survive and flourish.

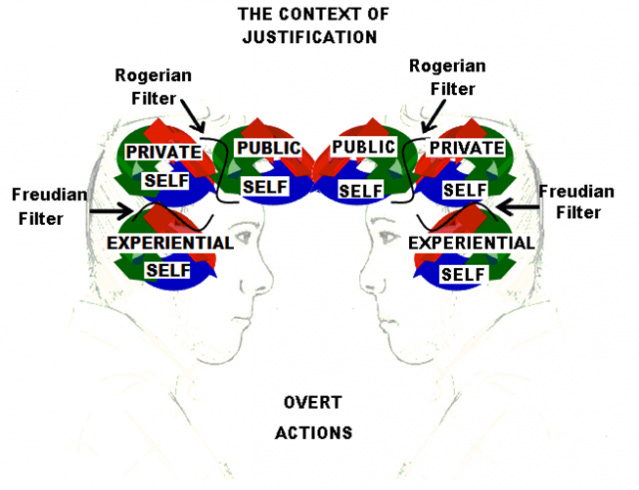

Systems 1 and 2 don’t act in isolation. Every decision we make involves some input from both systems. Henriques suggests that the relationship between these systems is best described by an updated Tripartite Model of human consciousness, similar to that first proposed by Freud (his famous Id, Ego, and Superego):

The Experiential Self: The part of us that directly experiences and acts upon unfiltered sensations, perceptions, motivational urges, feelings, and emotions; associated with the BIS and System 1 thinking.

The Private Self: The “centre of self-reflective awareness”8, associated with System 2 thinking; this part represents the self-focused half of our justification system, and is made up of the various internal narratives we spin to rationalise and make sense of our Experiential Self’s actions.

The Public Self: The image we project to others, also associated with System 2 thinking; this part represents the public-focused half of our justification system, and is made up of the stories we tell about our Experiential and Private Selves to others.

The Tripartite Model is thus an elaboration upon the basic process proposed by the Justification Hypothesis. The Experiential Self (BIS, System 1) drives us to act in self-interested ways, the Private Self (self-focused System 2) justifies or suppresses these actions so that a consistent, flattering self-concept can be maintained, and the Public Self (other-focused System 2) justifies the actions of the Experiential and Private Selves in the public arena.

I don’t think I need to say too much more on this. The Tripartite Model is one of those foundational ideas that most psychological theories take as given, so if you’ve read any psychology books at all, you already know how this works. The important thing to note here is that it all fits together. The Tree of Knowledge, Behavioural Investment Theory, the Justification Hypothesis, the Dual Processing Model, the Tripartite Model—these theories describe the most fundamental functions of the psyche, and together, they can explain all of human psychology.

At least, that’s what Henriques would have us believe. I think he’s pretty close, but you can make up your own mind.

That’s Quite Enough for One Post, Thank You

Henriques’ theory is complex and multifaceted. I would usually attempt a brief summary at this point, but to be honest, I’m not sure that I’ve entirely understood it all yet, and I don’t want to give the wrong impression. What I can say is that Henriques seems to be pointing in the right direction. Everything I’ve described in this post fits perfectly well with my previous writings on personality, cybernetics, and narrative and clinical psychology. There are many points of contact between Behavioural Investment Theory and Colin DeYoung’s cybernetic theory of personality; the Justification Hypothesis seems to describe the emergence of what researchers like Dan McAdams and Kate McLean call ‘narrative identity’; and it’s not hard to see how certain mental disorders could be explained by a dysfunctional BIS or conflict between our justification systems (our three ‘Selves’). Henriques’ explanation of how the BIS and justification systems emerged—the gradual unfolding of the Tree of Knowledge—also fits well with what we know about neurobiology.

I’ll leave it at that for now, but I will have more to say about the Unified Theory of Knowledge in future essays. In fact, I’m already working on several posts related to this topic, including the long-awaited final instalment of The Stories We Tell. If this interests you, consider subscribing to be notified of future posts.

Please also share your thoughts in the comments. Your questions, criticisms, and wayward reflections always help me to gain a better understanding of these difficult ideas.

Other posts I’ve written on psychological theory:

Further reading on Henriques’ Unified Theory of Knowledge

Henriques (2003), The Tree of Knowledge System and the Theoretical Unification of Psychology

Henriques (2011), A New Unified Theory of Psychology

Gregg Henriques’ Psychology Today blog

Henriques, 2003.

Henriques, 2011.

Henriques, 2003.

Definition adapted from DeYoung & Krueger, 2018.

For various reasons, Henriques now refers to the Justification Hypothesis as Justification Systems Theory (JUST), and uses some different terminology for the various elements of JUST. To keep things simple and consistent with the sources I used to write this post, I’ve used Henriques’ original labels.

Henriques, 2011.

More accurately, models—many similar ideas have been proposed.

Henriques, 2011.

Thanks for this. I am a bit surprised at the tone of some of the comments here. I found this to be a thoughtful presentation with an appropriate dose of humility. This is an interesting theory and I appreciate you introducing it.

Hey! Thanks for putting this together. Fascinating read of a researchers work I haven’t heard about before.

So much here, so I’ll try to be brief with the points I’m trying to hit here.

1. I like the BIT, especially the first principle. The more we can try to reduce the information of experience to energy then that leads to better science. It’s obviously the avenue we have to go down and there’s research at various levels of this (some more costly than others), but it’s good to try and come up with an idea to encapsulate it all. I also like that it leans towards nature as a driver of biological development.

2. Movement does seem to be a big factor in cognition. I like this quote:

“Henriques suggests that Mind—the ability to think, perceive, remember, imagine—emerged in animals as a consequence of their capacity for movement. “

And Barbara Tversky (wife of Amos Tversky, longtime close collaborator of Daniel Kahneman) has soooo much work on this point. She spells it all out in her book Mind in Motion.

3. The tripartite model of human consciousness, soooo many ways to spin this thing. I’m personally a dude who likes the Jungian framework of the the self and all that because it’s amazingly flexible and I think it works well in embracing the possibly infinite concepts our mind can imagine.

There’s probably more I can write about, but I’ll wrap it up here. Thanks again!